I love archives. They are the closeted glories of the museum world, and we do not do enough with them. There have always been too many gilded teacups and worthy portraits to put on show. But if we stop looking and start seeing, what riches lie hidden there?

In November 1884, a man with the rather unlikely name of Newton H. Chittenden submitted an Official Report of the Exploration of the Queen Charlotte Islands to the government of British Columbia.1 He had been hired by the chief commissioner of Lands and Works to survey Haida Gwaii (then called the Queen Charlotte Islands) and describe what he found. His report is, in its fashion, anthropological. He describes potlatches and dancing, religion and food, habits of dress and behaviour among “the Hydah” – that “very remarkable race of people” as he calls them. He was, as so many of us are , particularly won over by Haida carving. So he decided, like many a tourist supporting the local economy, that he would like one to take home. “Desiring to possess some small article of Hydah manufacture,” Chittenden wrote enthusiastically, “I gave a young Indian jeweller a two-and-a-half dollar gold piece at nine o’clock in the morning, with instructions to make from it an eagle. Before one o’clock the same day, he brought me the bird – so well-made that not many jewellers could improve upon it.”

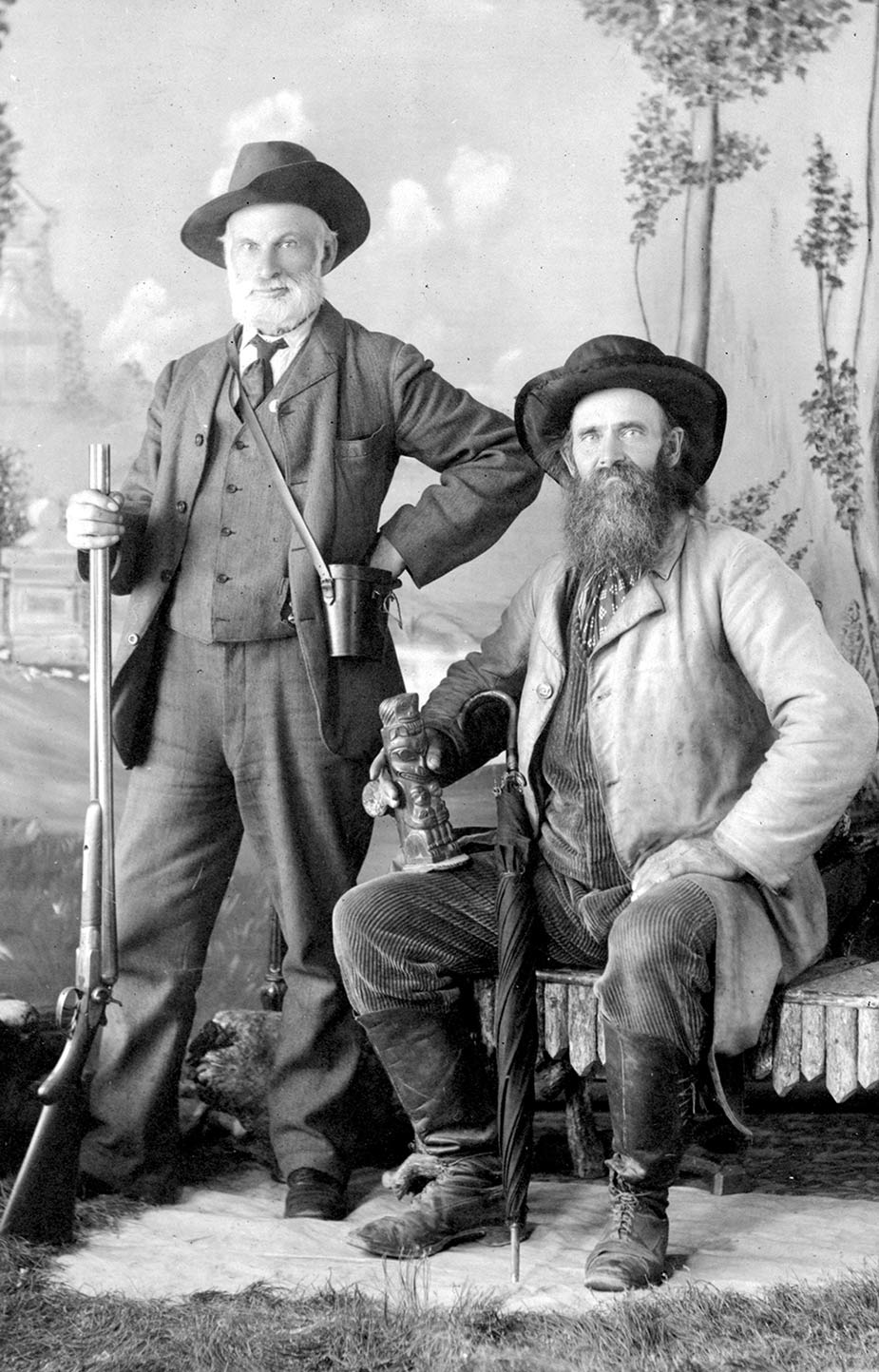

Chittenden was a fascinating character. At 70, he was the subject of a feature article in the New York Times, living out his days in New Jersey and starting each morning with a 20-kilometre walk before breakfast, dressed with post-modern abandon in a sombrero and sturdy corduroy trousers. In 1910, he was still every inch the explorer.

Richard Maynard and Captain Newton H. Chittenden (on right); just returned from their first trip to the Queen Charlotte Islands. Photo by Hannah Maynard, c. 1875. BCA c-08862.

And the story of his Haida gold eagle fascinates me. He didn’t spend his money: he transformed it. He was not picking up evidence: he was commissioning a work of art, one so refined that “not many jewellers could improve upon it”. His 1884 report on the Haida is (as you might expect) full of top-down attitudes that make us cringe today. But something else is also going on. Newton Chittenden was trying to see what’s there. He was trying to hear what the poet Susan Musgrave once called “the sound of nobody listening”.2 He may have been colliding with a culture he knew little about, but he was also connecting. And he may have provided a path for us today.

You could say – if we don’t press too hard on the point – that Chittenden collaborated with his Haida carver. It’s somewhere in there, with all those unspoken transactions between the two of them. Why an eagle? Why the emphasis on speed of execution? Who impressed whom here – the man who flashed his shiny gold piece or the man who shifted its shape? It is a matter not so much of whose but of what story we decide to narrate. Choosing what story we tell is, of course, something that all museums across the world have to ask, and not only ask at the start, but keep asking themselves. At my museum – the Royal BC Museum – the story is so well told, so comprehensive, that it almost engulfs itself: man and nature, landscape and population, the long past and the shifting future. As the story of British Columbia, it’s wonderful, and wonderfully done, as its nearly half a million annual visitors can attest. But what’s excluded here? What stories could the museum tell? Or any museum?

I want here to suggest some starting points for change at the Royal BC Museum, but my concern is less with the particular case than its implications for all of us. City or regional museums, or themed museums, are often so keen to master their histories that everything that doesn’t fit is muscled out. And any modern museum that has fixed its story is – if we’re completely honest – only a jazzed-up version of those dusty museums of bygone days, with their stuffed cases and unchanging displays. Museums are, by definition, about containment. But maybe we need to turn them inside out and create not just access, but a genuine openness to other voices, other ways. We need – and the metaphor should be applied widely – to bring in to the museum what doesn’t belong.

One of my favourite museums is Te Papa in New Zealand. It’s a striking building that overlooks the harbour in Wellington. What I like about it is that it manages to create an experience for the visitor – not through bells and whistles, flashing lights and whatever the museum equivalent of a rollercoaster might be (a very fast escalator, perhaps). No, it creates a satisfying experience by taking visitors inside a fully imagined, sympathetic environment. At Te Papa, the approach, the building, the collections, the displays, the programming seem of a piece. The museum gives you something solid and noteworthy – it’s certainly not amorphous – but it is also open to what you bring to the experience. The colours alone make me feel good. They seem to make sense of where I am and what might have gone on there. Without seeming homogeneous or monoglot, everything at Te Papa is speaking together.

Easier to achieve, you might say, if you’re looking over a sun-filled harbour in New Zealand. But Te Papa’s openness picks up on something recently noted in the World Cities Culture Report 2012, a survey of the cultural life of a dozen world cities from Shanghai to Mumbai, Johannesburg to São Paulo. The report notes that infrastructure – the hard build of bricks, mortar and the odd Corinthian column thrown in to let us know we are entering the temple of Culture – is by no means the only measure of cultural effectiveness. Cultural activity (festivals, street life, pop-up events) is, the authors write:

an increasingly important driver of a city’s appeal to residents and businesses alike. In this domain, the gap between the older, richer cities and those of the emerging economies is smaller, and on some of these indicators the emerging cities outscore the older cities – in part, because they are often larger. These wider measures of vitality and diversity suggest that the world cities are more balanced culturally than simple counts of, say, museums would indicate.

It’s an interesting point and affects a number of issues, from how museums will have to rethink themselves within such active cities, to how we will compete with changing types of cultural attraction. It also affects how we set about our own cultural advocacy: to the public, to potential funders and to government. In Canada, as in many countries, the model is increasingly moving away from a dominant national policy toward a more localized and autonomous cultural sphere,4 so one way in which museums will thrive is by plugging into the informal cultural activity around them. Museums are rarely comfortable doing this. They usually have very big doors with very strong locks to keep the world out. But as Te Papa shows, openness can become a way of working.

And if the result of collaborating with the wider culture is greater vitality, diversity and cultural balance – to use the terms of the World Cities Culture Report – so too is the geographical extension of that engagement: not just drawing energy from the cities where we are, but creating new synergies with other cities and towns, other regions and countries. Part of the Royal BC Museum’s mandate is province-wide, and this covers a number of areas: advising on collections and conservation, sending loans and travelling exhibitions, mentoring and training museum colleagues. Aliens Among Us – a fascinating look at the 4000 natural species that have come (like many of us) to live in BC – started life as a successful Royal BC Museum exhibition. It is now travelling to nine museums across the province over a two-year period: from Nelson to Kitimat, Penticton to Prince George. It’s an excellent way to raise the profile of the provincial museum and its partners, and to collaborate on new programs of engagement for young people, adults and others across the region. But is it enough? It feels like one tenuous thread across a province that occupies 10 per cent of Canada’s land surface. With an area of 95 million hectares, British Columbia is larger than France and Germany combined. If this is our cultural Trans-Canada Highway, we need to get more traffic moving along it!

Indeed, I want to extend this looking out even further. Collaborating can seem a bit like holding hands on a first date. Very safe. Very cosy. Sure, let’s connect. But frankly, I want a few cultural sparks to fly too. I want some real difference, not just complementarity. We shouldn’t be afraid of it. The most popular music downloaded from iTunes is often a mash-up of artists and songs, old and new, samples and remixes. It’s what I want for museums. Some days, just like in the real world, I want my culture to collide.

The Canadian writer Jack Hodgins wrote a wonderfully entertaining novel called The Invention of the World. The boarding house he describes on Vancouver Island is, in its zany way, a kind of west coast museum of characters and ideas, a living cabinet of curiosities. The boarding house proprietor Maggie – the novel’s equivalent of me, if you will – knows exactly what she’s got. As Hodgins writes:

She had a perfect set-up. She had this land, opened up to the whole wide strait along this edge as if there were no real borders on her world … a solid base from which to rise.5

Standing outside my museum, looking out over the water, I know how she feels. The landscape inspires me to infinite possibilities. But if I’d like to encourage not just mine but all museums to open up, look outward and make more connections, I think museums also (particularly in times of economic difficulty) need to look inward, to make sure they have “a solid base from which to rise”. We have to start by collaborating with ourselves.

One way we can do this is by keeping our permanent galleries fresh. Think of Newton Chittenden. Think of the moment he and the Haida carver meet. That’s the feeling we need to get into our public spaces. It’s something more than precious objects or helpful information or re-enactment. It’s a kind of sympathetic awareness and imaginative power that we need to build into the museum experience. If I don’t feel it, no amount of text or impressive display is going to make me feel it.

It’s not a question of externals either – of big shot architects or glamorous imported exhibitions. It’s about reinventing what we have. If we rethink it, so will the public. We sometimes know our own collections so well that we only see the catalogue we’ve inherited: here are the fixed categories, here’s what we have, here’s what we say about it. It may all be very worthy. But the world around us is changing all the time. What people do, what they think, what interests them is constantly on the move. Coming from London, I know how exhausting this can be! But what power was there, once we found ways to bring it into the museum. Get out into British Columbia, and you can see mighty rivers converted into electricity. That’s our model. We have to transform history into light. We have to be as wide and open to the skies as the Peace River. We have to be hydroelectric.

I am not about to set up a new income stream for the museum by taking on BC Hydro. But I do want to suggest two ways in which we can generate power from our collections. One is by celebrating the individual. There is an understandable push to get as much of our collections on display as we can. It’s a laudable instinct, especially when the public are frustrated that everything we hold isn’t out for them to see. They want it all! But selection is one of our greatest assets. Of course there are times we want to show variety, development; quantity can be impressive at times. But think of some of your most powerful experiences of art or nature. Is it not the single artwork whose very uniqueness is enhanced when it appears alone? Is it not the apparition of a solitary Mule Deer, still and watchful at the forest’s edge? If our displays can achieve the force of concentration, think what we can do with them. Rather than engulf the visitor, we can get them to ricochet from one great event to the next, so that they come away not just remembering a landscape or culture, but enchanted by the droll coral-striped beak of a single Tufted Puffin, or the towering authority of a Kwakwaka’wakw totem pole.

So powerful is the unique that it needn’t restrict itself to the obviously beautiful. Puffins and totem poles are easy sells – but we need to dig deeper. At the Royal BC Museum we are about to display one of British Columbia’s earliest land treaties. Signed in the 1850s by the governor of Vancouver Island James Douglas, the treaty is just the sort of cultural moment we saw with Newton Chittenden on Haida Gwaii – and one with much greater long-term effects. This is the moment, there, on the page, stuck with bits of bark and other material, when the representative of the British crown colony seals the deal with representatives of Vancouver Island’s First Nations. It looks like connection; it feels like collision; it certainly wasn’t collaboration.

It is a legal document, really; a bill of sale; a text we could reproduce online or on the wall. But how potent it is, that physical bit of paper. Everyone in Canada lives on the result. And it was until recently tucked neatly away in the museum archive.

I love archives. They are the closeted glories of the museum world, and we do not do enough with them. There have always been too many gilded teacups and worthy portraits to put on show. But if we stop looking and start seeing, what riches lie hidden there? And this brings me to my second approach to recharging the museum from within. We have to communicate our assets. It’s not just the collections, but the archives themselves – all that history and research – that need to be better known. We need to get learning programs that delve in and create new approaches, new topics for us. We need to stop talking at the young and start asking them what they want to know. We need to digitize, not only so that we can speak to the world, but so that the world can speak to us. Te Papa has a Soundings Theatre and Te Marae, a place where all can stand and all can belong. That’s what I want for my museum. A warm welcome for those who are arriving, and a sense that everything – the collection, the archives, the visitors, the staff – belongs. I want so much collaboration that we stop using the word “collaboration”.

Across British Columbia you will find three UNESCO world-heritage sites. It is an impressive number, and if you get a chance to explore them, they will remind you of an essential attribute of the past and present culture here on the west coast: that we always see ourselves in relation to the mountains and the forests and the sea. As Jack Hodgins’ heroine Maggie understood looking out from her Vancouver Island boarding house, British Columbia is not so much at the edge of the world as on the cusp of it – as if, as Hodgins says, “there were no real borders on her world”.

And that’s how I want the Royal BC Museum to be: on the threshold of the world. Open to its currents. Ready to extend an invitation to all. Any museum can be that – intellectually, in terms of vision. But here in BC the land and the ocean are much more than a picture postcard backdrop. They colour everything, shape every experience. Find me a visitor who hasn’t marvelled at the Rocky Mountains behind, the Pacific before, trees so wide you can’t see past them. That’s the scale of experience here, that’s daily life, and unless the Royal BC Museum finds its analogy to this, it is never going to match the power and beauty, the expressiveness of what surrounds it.