A Modern Linkage to Francis Drake

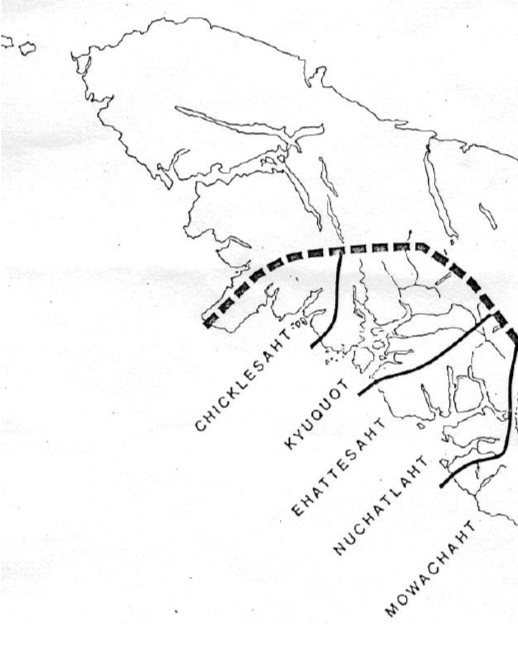

Figure 1. Approximate location of traditional territories of Nuu-chah-nulth tribes to the south of Brooks Peninsula.

Information about First Nation practices on the West Coast of Vancouver Island have been interpreted as possible evidence of a visit by Francis Drake – rather than the well documented voyages of Juan Perez in 1774 or James Cook in 1788. Part of this is based on a tradition among the Che:k’tles7et’h’ (Chicklisaht) people of the west coast of Vancouver Island who had a ceremony which involved providing food to a “traveling chief” from the sea – a tradition different than all the other Nuu-chah-nulth tribes related to the Chicklisaht (sometimes spelt “Chickleset” and “Checleset”). Juan Perez did not land on Vancouver Island but did trade briefly off shore with a few Hesquiaht people in a canoe. James Cook anchored much further south of the Chicklisaht at Resolution Cove, in the territory of the Muchalaht, and interacted mostly with the Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’ (Kyuquot) people of Yuquot.

The Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/ Che:k’tles7et’h’ are today part of the Maa-nulth Treaty group along with the Toquaht, Uchucklesaht and Ucluelet First Nations who completed a final treaty agreement with Canada and British Columbia under the B.C. treaty process that came into effect April 1, 2011 (see figure 1 and 2).

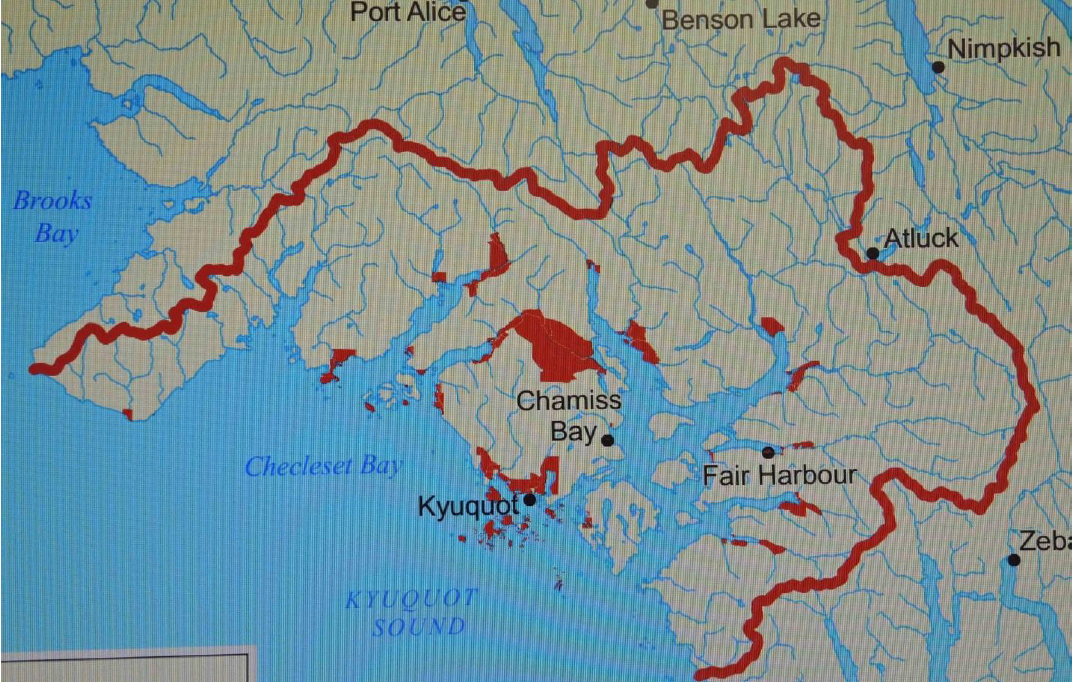

Figure 2. The combined Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/ Che:k’tles7et’h’ territory recognized in the 2011, treaty settlement. The old village of Upsowis is in the red area at the left entrance to Malksope Inlet above the name Checleset Bay.

The first Europeans to anchor in Chicklisaht territory to the south of the Brooks Peninsula were James Colnett in the ship Prince of Wales and Charles Duncan in the Princess Royal in 1787 (see Galois 2000:69-91 for details). The information of interest here is that reported on June 24, 1791, by John Hoskins, the ship’s clerk on the Columbia Rediviva, which visited the village of “Opswis” [Upsowis] in Chickleset Bay to the south of the Brooks Peninsula. Upsowis is located at the east entrance to Malksope Inlet to the north of the Bunsby Islands. Hoskins describes

how they were seated and fed and: “after this entertainment, we were greeted with two songs; in which was frequently repeated the words “Wakush Tiyee awinna’, or “welcome travelling Chief.” These were sung by a great concourse of natives, who came from all parts of the village to see us, for it is very probable we are the first white people that ever was at their village, and the first many of them saw”

(Howay 1990:191-192).

Anthropologist Susan Kenyon noted: “The fact that the first White people in the area went to Chickleset territory (Ououkinish Inlet) is well accepted in the Kyuquot area. The Chickleset people still claim details of these stories as their private property and celebrate them in potlatches and song. Without knowing much of the recorded background history, however, people today claim that this meeting took place “before Captain Cook came” and was with a Spaniard. It is not unlikely that one of the Spanish exploratory voyages from California in the 17th or 18th centuries did get blown off course and met the Chickliset people; the meeting was not repeated (“They promised to come back, but never did,” I was told) and unless details of it are unearthed from a search of the Spanish records, it must remain a mystery.” (Kenyon 1980:42).

In the early 1980s, Peter Webster, an Ahousaht Elder, talked to the author (Grant Keddie) about Sir Francis Drake. Peter went to a lecture on Francis Drake when he was in San Francisco in the 1960s. He told me about the Chicklisaht practice of feeding “the visitor from the sea” during a feast, and thought that tradition might be referring to the visit of Francis Drake. This unique practice of putting food into the sea was also told to the author by Ahousaht Band member, the late Dr. George Louie (February 19, 1912 to July 7, 1995) in 1994. George Louie worked at the Royal B.C. Museum as an affiliate in anthropology in the late 1980s and early 1990s. He worked on transcribing, into English, a backlog of tape recordings of Nuu-chah-nulth elders speaking in their native language. Dr. Louie was also working with linguist Thomas Hess of the University of Victoria in the creation of an Ahousat dictionary. George Louie knew about the story of the Chicklisaht feeding ceremony from stories he heard from elders that had died, and he was aware of the beliefs of other Nuu-chah-nulth, that is Peter Webster and Noah Smith, who were connecting the ceremony with Francis Drake.

Noah Smith was interviewed for an article written by journalist Arthur Mayse in 1982. Mayse notes that: “When I was a boy in Nanaimo, the occasional youthful expedition still shoved off by cabbage-crate boat to dig for ‘Drake’s Treasure’, which was reputed to lie hidden somewhere near the Malaspina Galleries, a series of sea-sculptured indentations in the Gabriola Island bluffs”. Mayse goes on to say: Noah Smith, whose wife, Martha, is a weaver of note, dropped in at out Campbell River museum a while ago. My wife, a museum volunteer, got to talking with Noah. The subject of the old navigators came up. Noah mentioned Drake’s voyages, and even sought help from the British Museum in an attempt to fill in the 68-day gap in Drake’s record of his West Coast cruise” …”Noah Smith’s good friends’ the Chikliset of Queen’s Cove near Zeballos, may hold the key. Quite simply, they believe that for at least some portion of that period, Francis Drake was their honored guest. Like every other Indian band, the Chikliset have a wealth of tales and legends handed down from one generation to the next. One of the oldest of these stories has to do with big, hairy men (the words are Noah Smith’s) who arrived in their cove on an enormous floating house, led by a great chief from beyond the horizon. This countless moons before the arrival of Captain Cook.

Nor is it only in legend that the visit by these bearded men in their floating house is celebrated. The band also has its traditional songs and dances. One of the Chikliset’s oldest songs has to do with the arrival of the visitors and their welcome. There is also a most peculiar potlatch custom, which Noah Smith believes to be unique among this band. It is a tradition of all potlatches up and down the coast that the first gift is given to the most honoured guest. But in the case of the Chikliset, no present guest is awarded their ‘gift of honour’. The gift is carried down with great ceremony to the water’s edge. There it is dedicated to ‘The great chief beyond the horizon’ … a chief whom Noah Smith is utterly convinced was none other than the intrepid sailor who returned to England to become Sir Francis Drake. As I said at the start, the winds of romance blow along this wild and wonderful coast. And who’s to say that matters didn’t fall out in the long ago precisely as Noah Smith and the Chikliset people believe they did?”.

When examining First Nations oral histories, I tend to put more trust in information placed in written form by 19th and early 20th century authors who have at least some understanding of the traditional culture they are recording or preferably by an author who is writing the information down (from a First Nation consultant) in a known linguistic script that is then interpreted in a European language. In the older documented stories it is difficult to tell if a tradition pertains to events that are 200 or 500 years old unless there is some indication in the story as to how many generations back the story goes or if it pertains to known events that are independently documented. More recently written 20th century First Nations stories that have no previous archival history can easily be re-interpreted in light of more recent influences found in reports, books or on television. I am presenting this fragmented information here, so that future readers can incorporate it into their assessment of the stories of early visitors.

References

Galois, R.M. 2000. Nuu-chah-nulth Encounters: James Colnett’s Expedition of 1787-88. In: Nuu-chah-nulth Voices, Histories, Objects & Journeys, pp. 69-91. Edited by Alan L. Hoover. Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria, B.C. Canada.

Howay, Frederic W. 1990. Voyages of the “Columbia” to the Northwest Coast. 1787-1790 and 1790-1793. Oregon Historical Society Press in cooperation with The Massachusetts Historical Society. (Originally published in 1941 as volume 79 of the Massachusetts Historical Society Collections).

Kenyon, Susan M. 1980. The Kyuquot Way: A Study of a West Coast (Nootkan) Community. National Museum of Man Mercury Series. Canadian Ethnology Service. Paper No. 61. A Diamond Jenness Memorial Volume. National Museums of Canada. Ottawa.

Mayse, Arthur. 1982. Campbell River Upper Islander, February 17, 1982.

Webster, Peter. 1983. As Far As I know: Reminiscences of an Ahousat Elder. Campbell River Museum and Archives, Campbell River, B.C.