Piecing together Outsiders Views

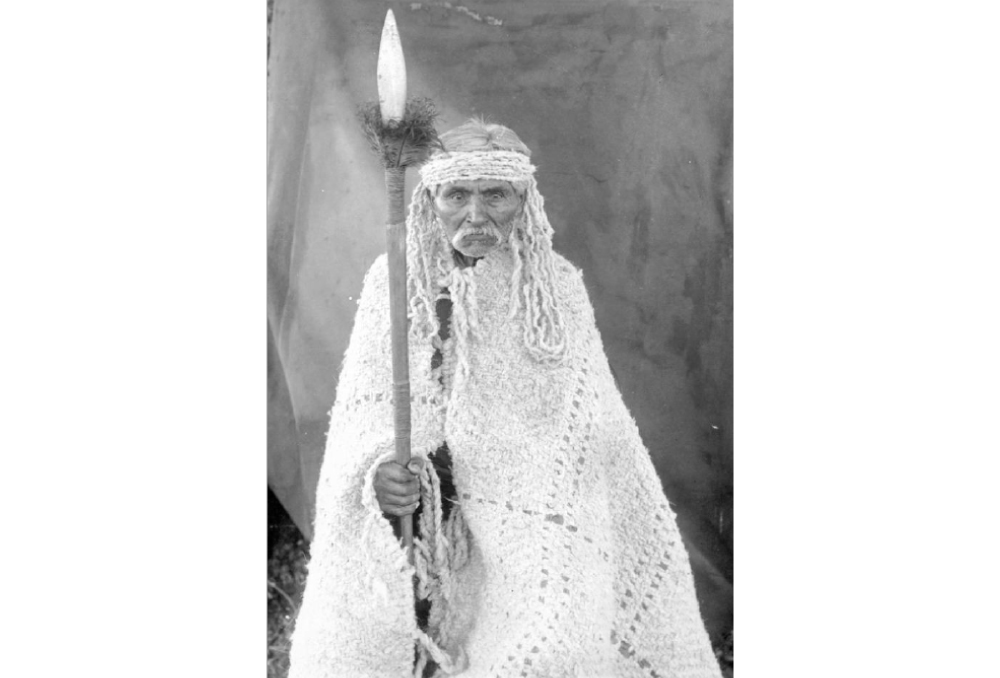

Figure 1. Chief David Latasse photographed on the Tsartlip Reserve in 1922, at age 61-64 (RBCM PN6165).

David Latasse was a Tsartlip (W?JO?E?P) First Nation. They are part of the Saanich (W?SÁNE?) peoples whose territory is centered on the Saanich Peninsula and southern Gulf Islands. Latasse gained notoriety from 1927-1936 as a speaker in his native language at ceremonies, the subject of an early movie maker and as a source of information via translators for newspaper reporters and at least one anthropologist. He was born about 1858-1863 and died May 2, 1936.

For most of his life he lived near his mother’s relatives on the Tartlip Reserve located on the Saanich Peninsula north of Victoria. We are fortunate to have a letter that was dictated by Latasse himself and addressed to the Department of Indian Affairs on June 25, 1903:

“I now live at Saanich on the Sartlip Reserve and have lived here for the last 25 or 30 years. My father was a Songhees Indian and my Mother was a Saanich women. I was born on the Songhees Reserve and lived there until I was about 15 years old and then came to live at Sartlip Reserve. My Grandfather and two brothers are buried on the Songhees Reserve. My grandfather’s name was Skull pult. I don’t remember the names of my brothers I know where all their graves are.”

David Latasse would, by his own statement, be 40-45 years old at the writing of this letter, which means he was born around 1858-1863 or 15 to 20 years after the building of Fort Victoria. His age later became a subject of controversy but was play-up by newspaper reporters perpetuating the stereotype of Latasse as an “ancient” man with a fountain of all knowledge.

Figure 2. Home of Chief David Latasse on the Tsartlip Reserve in 1922. First house on the waterfront at the left of the photo. (RBCM PN11740).

Figure 2. Home of Chief David Latasse on the Tsartlip Reserve in 1922. First house on the waterfront at the left of the photo. (RBCM PN11740).

In his old age Latasse appeared to change the stories of his earlier life to make it seem that he was much older than his true age and the stories he told of his father’s generation were part of his own experience. But, it is uncertain how much of this was a result of his interpreters and the stereotyping of newspaper reporters. Some newspaper reporters seem to have preferred to exaggerate his age as he got older.

The first published newspaper commentary on Latasse appeared in association with the visit of the governor-general of Canada in 1927. Latasse spoke at a special ceremony held at what is now Kosampson Park on the upper Gorge Waterway. The event was to initiate the governor-general as honourary Chief Rainbow (Keddie 1992).

Figure 3. Canoes of First Nations and government officials in Victoria Harbour heading up the Gorge Waterway on March 30, 1927. David Latasse is in the canoe at centre in the poka-dotted white cape with Chief Alex of the Malahat and Chief Cooper of the Songhees in front of him and the Viscount and Lady Willington behind them (Keddie postcard collection).

Figure 3. Canoes of First Nations and government officials in Victoria Harbour heading up the Gorge Waterway on March 30, 1927. David Latasse is in the canoe at centre in the poka-dotted white cape with Chief Alex of the Malahat and Chief Cooper of the Songhees in front of him and the Viscount and Lady Willington behind them (Keddie postcard collection).

More information about Latasse appeared on March 15, 1931, as part of a sequence of articles titled: Soliloquies in Victoria’s Suburbia by Nancy de Bertrand Lugrin – the wife of the editor of the Victoria Colonist. In speaking about the Tsartlip Reserve Lugrin mentions:

“The present chief is David, a very ancient man, who claims to be more than one hundred and speaks only Chinook. If one goes to see him his wife will do all the talking. His present wife does not look more than forty. Occasionally she will translate a question for him to answer. But he says little, though he is pleased to have visitors. His lodge is a fairly modern house, and the living-room a large one.

The chief will tell you, through his young wife, something of his early days. Particularly he likes to dwell upon the part the Indians used to take in the regatta on May 24 in the years gone by. They would practice for this event during the whole year, going out every night in their racing war canoes, for the rivalry between the various tribes for the honor of winning in these events was very keen. They got good money, too, from eight to ten dollars a paddle. One could have a rather fine celebration on eight or ten dollar, he says. But the present-day members of this reserve take little or no interest in the regattas nowadays. ‘It’s too much work’, says old David, ‘for the amount of money there’s in it, and they won’t pay, as they used to do, whether the boats crew win or not.’”.

On July 12, 1931, Lugrin writes about the burial sites among the Saanich and mentions that:

“Just now Chief David is away ‘in the States, for berry picking.’ He is about eighty years old, but that does not deter him from traveling and working. He goes every year at this time. When he returns we are to learn from him some of the old legends of the Saanich Indians with their place names. Tunen, which is the lovely slope of land which faces the southern side of Mount Newton; Omysuk, which is Mackenzie Bay; and the story of Tlespace, the great bare rock in this vicinity which we are told every fisherman knows; Oluktuts, which is Goldstream, and many another. Only old David has the history of Saanich Indians in his head, and he knows no English. But his Indian is very graphic and complete’”.

This is, of course, a stereotype built around Latasse as the fountain of all traditional knowledge. There were certainly other Saanich elders who were knowledgeable about the past and had personal family histories not known by Latasse. To this day, many Saanich families have contributed to providing traditional place names (see Hudson 1970 and Elliott 1990).

On August 23, 1931, another article appears in which Lugrin talks to Latasse after his return from berry picking:

It is wonderful and a precious thing the saga he sings, for with him it will die, and no one will ever hear its cadences again. Therefore we had with us as interpreters Frank Verdier, who speaks Chinook as well as anyone versed in that coast jargon, and Paul, who might have been chief but he was too young. Then there was Mrs. David to help now and then. Paul knows well the musical Indian language of the Saanich tribes, and it is that medium which Chief David mostly employs, though he is fluent in Chinook and knows a little English as well.”

After talking on about Latasse’s mannerisms of speaking, Lugrin notes: All sorts of stories have been told about the chief’s age. When he was received by His Excellency Lord Willington, the Governor-General of Canada, a few years ago, it was said that he was a centenarian. We believe that is wrong. He thinks he is well over a hundred. But Frank Verdier says he cannot be much more than ninety. He doesn’t look over seventy.” Lugrin then chooses to ignore what she just said and focus on the stories that Latasse was a young man at the time of the founding of Fort Victoria in 1842, which would imply that he was in his late 90s.

Lugrin mentions that they “were anxious to learn what the chief could remember of the stories his own father used to tell him”. Latasse is quoted as saying: “Many stories my father has told me of how every summer the Indians from Cape Mudge, the Yucultas, would come down and fight the Songhees, the Saanich tribes and the Cowichans. They would come in their huge canoes, many warriors, and steal upon the villages by night. ‘Always they came for the same reason, to kill the men and to steal the women and young girls, so they might sell them for slaves and become rich. For blankets they would sell them over across the water on the United States side, for blankets and canoes or any other thing the Indians valued’”. Even today you may see throughout the woods in Saanich great pits which have been dug long ago, and which are not yet filled in, so deep they are. That is where the Indian men would hide their wives and children when the wars were on. There they must always sleep at night, so that no enemy Indian stealing through the tree in the dark could find them”.

On August 8, 1931, Latasse’s story is told about the great battle of Maple Bay, where many local First Nation warriors joined the Cowichan to defeat the northern invaders from the Cape Mudge region. On October 18th, Lugrin provides more information about Saanich place names. When trying find out the name for Saltspring Island she says:

“Chief David’s memory is remarkably good, but he does disappoint one occasionally and may have forgotten this. Here are a few names as near as we could get to the spelling. Tod Inlet was known to the Tsautups [Tsartlips] as ‘Snitqualt,’ but the meaning of this euphonious cognomen he could not tell us. Butchart’s Bay was ‘Humsawhut.’ Meaning Sunshine Bay. The bay at the foot of Verdier Avenue [north end of Brentwood Bay] ‘was named for a man who died. We call him ‘Skahasin’.

Another source for Latasse’s stories appears in the Saanich Peninsula and Gulf Islands Review on March 14, 1932 (p.2), entitled: “Aged Chief Tells of Olden Times”.

“The editor of the Review, through an interpreter, recently interviewed the oldest Indian Chief Latess of the Brentwood Reserve, who claims to be 120 years old”. On the topic of extreme weather Latasse indicated that: “some 130 or 140 years ago, according to the information given by the chief’s father, there was an unusual winter when snow fell to a depth of 14 feet on the level and remained for a considerable length of time. Many Indians starved to death as a result, the snow being too deep to procure wild vegetables from the fields and wild game soon being depleted.”

Maclean’s Magazine and the Creation of a Costume

The notoriety of David Latasse had caught the attention of Maclean’s Magazine. On December 15, 1932 (p22&38) they wrote “Indian Saga” which included Latasse’s story of the “Last Great Battle”. “David La Tasse is the oldest living chief on the North pacific Coast. He claims to be more than 100 years of age, and he can remember ‘Jim” Douglas very well – Sir James Douglas, first governor of British Columbia – also the building of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fort, where Victoria stands today”.

It would appear that Maclean’s arranged for Victoria’s Ernest Crocker of Trio Photography to take photographs of Latasse in what was to be a traditional costume. One of, at least three, images that he took appears in the Maclean’s article (Figure 4, RBCM PN117781). Another, (RBCM PN11778, Figure 6), appeared later in the Victoria Daily times on July 14, 1934 and the other (RBCM PN11743, Figure 5) was not used.

Latasse was holding the same spear, but wearing a different outfit than in the 1927 images. The outfits worn are very much like the large woven blankets made in 1927 for a Tipi constructed for the visit of the Governor-General of Canada (see Keddie 1992).

Figure 4. David Latasse in 1932. (RBCM PN11781).

Figure 4. David Latasse in 1932. (RBCM PN11781).

Latasse was interviewed by the well-known Canadian ethnologist, Diamond Jenness between 1934 and 1936. Using less flowery language than the reporters that proceeded him, Jenness recorded that:

“David LaTesse received his 1st name when he was a little child. There was no potlatch and he does not remember what the name was. He received his second name at a potlatch when he was 12 years old. The new name was qalek waltan (no meaning); it was given him by his grandfather and had belonged to some grand uncle. He received his 3rd name when he was 14. His father conferred it on him. It was the name sxa wal

‘whirlwind’ of his great grandfather who had lived at Sooke. This name goes to the oldest son in the family. The name haiel wat (thunder) goes to the eldest daughter. The name talsit (lightning) to the 2nd son. Sxwa wal remained his name till he was about 50. Then, at a potlatch, he gave himself the name steel um (no meaning), after his mother’s father. This name he still bears” (Jenness 1934-36). Jenness gave David’s age as 85, which would place his birth c. 1849-51.

Figure 5. David Latasse in the middle, with Tommy Paul of the Tsartlip Nation on the left and Chief Edward Jim of the Tseycum Nation on the right, in 1922. (PN11743).

Figure 5. David Latasse in the middle, with Tommy Paul of the Tsartlip Nation on the left and Chief Edward Jim of the Tseycum Nation on the right, in 1922. (PN11743).

Reporter Frank Pagett, writing in The Victoria Daily Times on July 14, 1934, made Latasse considerably older with an article entitled: “105 years in Victoria and Saanich. Chief David Recalls White Mans’ Coming”. By Latasse’s original accounts he would be about age 72-77 at this time.

There was often confusion by reporters about whether Latasse was recalling stories from his own observations or from those of his father’s experience. Latesse provided stories for the newspaper about known historic activities that were clearly out of sequence, mixed up versions of events, such as the observation of the first European ships and the first bringing of cattle to Victoria – which did not occur until several years later – or his suggestion that there was a central camp on Mud Bay where the Empress Hotel and the Union club were located – no evidence of an archaeological site has been found in the historic excavations in this area. Pagett noted that Latasse was “mentally keen, although extremely fragile”. He “was looked after by a well-educated wife, half his age, who aided in interpreting the ancients vigorous statements. The principal interpreter of Chief David’s reminiscences was his grand-nephew, Baptiste Paul, professionally known as Baptiste Thomas, a boxer and wrestler, whose prowess has won fame throughout the Pacific Coast”.

Latasse gave the reporter a political statement about being present during the 1852 meeting regarding the Saanich treaties and interprets the treaties not as a purchase of land but of agreements to use parts of the land for annual payments of rent:

“More than eighty years ago I saw James Douglas, at the place now called Beacon Hill, stand before the assembled chiefs of the Saanich Indians with uplifted hand … I heard him give his personal word that, if we agreed to let the white man use parts of our land to grow food, all would be to the satisfaction of the Indian peoples. Blankets and trade were to be paid. We knowing a crop grows each year, looked for gifts each year. What we now call rent. Our chiefs then sold no part of Saanich”.

Figure 6. Chief David Latasse in 1932. (RBCM PN11778).

Figure 6. Chief David Latasse in 1932. (RBCM PN11778).

The above statement is one that parallels the statement given by Latasse in a letter of April 4, 1932 to Commissioner William Ditchburn with a letter of support from five Chiefs identified as Saanich and witnessed by Simon C. Pierre from the Stolo Nation who was referred to as an “Indian Lawyer” (Latasse 1932). On the same Times article page the relevant sections of the Douglas Treaties referred to by Latasse were published under the title: “Saanich Title Deeds Denounced by Chief”. Latasse was successful in getting across his interpretation of the Douglas Treaties.

Here, Latasse tells a different story about his coming to Brentwood Bay than in his earlier letter version:

“When I was seven years of age I went to Brentwood Bay to live, joining aunts who had become wives of members of the Saanich tribe”. He is quoted as saying that he was 14 years old when the First Europeans came to Victoria Harbour, but this is similar to the age he gave in 1903, for when he moved from the old Songhees reserve to the Tsartlip reserve. This statement may have been misinterpreted in the translation to English. One of the photographs taken by Trio Crocker two years earlier appears with this story (RBCM PN11778).

The Colonist newspaper reports on September 4th, 1935 (p.2): “Centenarian Chief of Saanich Tribe Dances for Movies”. Chief David “being 109…donned his ancient tribal garments and did the Sun Dance before a motion picture camera of Hugh A. Matier, public relations representative for the Union Oil Co. of California …in color …Mr. Matier took 2000 feet of film on Vancouver Island, featuring Indians. … Mr. Matier left yesterday afternoon for Seattle. He expects to return to Vancouver Island next April in search of further interesting material for his lectures.”

The Reporting of His Death

David Latasse died the next year on May 2. The Times Newspaper (p.1-2) provides further miss-information on Latasse’s age, social status and the events of his personal experience: “Chief David Dies at 109″ – “Head of Songhees Indians Remembered Founding of Fort Victoria” … died at his home on the west Saanich reserve this morning”.

The Times mentions the events of the previous summer when Latasse “put on his ceremonial dress to dance before the movie camera.” This is a reference to the American producers mentioned above that made a movie of Latasse dancing.

The next day on May 3 (p.1) the Colonist, with the headline: “Centenarian Chief Passes” repeats the statement of the Times that Latasse died “at the age of 109 years”. The romanticized article by reporter and amateur historian Bruce McKelvie is accompanied by a photograph of Chief David with a woven blanket and spear. “He is pictured above, as he appeared not long ago, when he donned his old-time regalia as a warrior chief.” – “Death Takes Chief David” – “On the Indian Reserve at Brentwood Yesterday morning. … Chief David was a fine type of man. His influence for good among his people was extensive, and his example was an inspiration. He was highly respected by whites as well as by his own people. He recalled the attack by Cowichan and Songhees Indians on Fort Victoria, and was present at the great conclave at Beacon Hill when Governor Douglas extinguished the Indian land title by purchase. … and only last Summer donned his picturesque costume and executed some of the ancient dances before the lens of a motion picture camera. …his name will become a legend and his memory an inspiration to his people – Peace to his ashes”.

On May 8 (p.5) the Saanich Peninsula and Gulf Islands Review under the title “Link with Saanich is Severed by Chief’s death”. The editor notes that: “despite his age, which according to different sources is stated to be anywhere from 110 to 122, was surprisingly energetic to the end”.

Not long after, on May 17 (p.6), the Colonist published another article by Nancy de Bertrand Lugrin about the famous battle of Maple Bay entitled: “Chief David’s Saga”. Here he is telling his father’s experiences when referring to the battle of Maple Bay. The story also appears in Maclean’s Magazine on December 15, 1932, (p.38)

The Latasse version of the lead-up to the Maple Bay battle is recorded as follows:

“For many years, all in the bright summer weather, they have come down upon us, those Ukultahs [Lewiltok] of the north. They have killed our men and taken away our women to slavery. Every year they come and nobody knows whose house shall be left desolate with the ending of summer. They are many and strong and their canoes upon the sea are as the salmon in the spawning season at the river’s mouth. We cannot stand against them. We are too few. We are not united as they are. Year after year we wail the loss of our champions, the loss of our wives and children.”

Latasse provided information on some basic economic activities of “long ago”:

“In July the deer are very fat, we dig our pits for them. In August we hunt the elk with bow and arrow in the swamp lands. The clams too, are fat in August. Always in these days the women are very busy, roasting the meat and drying it for winter; roasting and drying the clams. In August also is the big fishing for tyee salmon, which we dry. All these things we store in cedar bark boxes and hang in our houses. …We gather plenty of bark from the fir trees, big pieces of bark and store it under the wide seat which runs all-round the house. There is plenty of wood for all the cold weather. Only bark we burn, nothing else. When winter come, for four months there is good time. Dancing and feasting and making happy. Nobody sad at all. Everybody laughing like children. Everybody giving parties. You come to my house. I give you present. I go to your house you give me present. All the time like that. Very good”.

Sixteen years later in 1952, Lugrin published a series of articles based on early interviews with Latasse. These included: “Memories. Stories Chief David Told Me” in the Sunday Victoria Times Magazine on April 5 (p.5), where Lugrin notes that: “With the late Frank Verdier and Chris Paul to act as interpreters, we went several times to call”. An article on April 12, was titled:

“Chief David’s Stories – No. 2. Indian Tribes Win Vicious. The Battle at Maple Bay”. Lugrin points out here that the battle “happened when David’s father was a young man”. The story was continued with an article on April 19 (p.5): “Chief David’s Stories – No.3. Triumphant Indians Sing Victory Paean”.

David Latasse was respected by his own people. From the time of the visit of Governor General Willington in 1927, to his death in 1936, Latasse was seen by non-First Nation reporters as an icon representing the romanticized version of the history of local First Nations. David Latasse, however, took the opportunity of playing this role in order to tell his version of history as he remembered it.

References not fully cited in text

Elliott, John Sr. 1990. Saltwater People as told by Dave Elliott Sr. Native Education. School District 63 (Saanich). Edited by Janet Poth. Revised edition.

Hudson, Douglas (compiler) 1970. Some Geographical Terms of the Saanich Indians of British Columbia with information from: Mr. Richard Harry, East Saanich; Mr. Ernie Olsen, Brentwood Bay; Mr. Christopher Paul, Brentwood Bay; Mr. Louis Pelke, East Saanich. Manuscript. McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario.

Jenness, Diamond. 1934-36.Diamond Jenness, Coast Salish Field Notes. Manuscript #1103.6, Ethnology Archives, Canadian Museum of Civilization).

Keddie, Grant. 1992. Installation of a Songhees chief. Discovery. Friends of the Royal British Columbia Quarterly Review. 20:1:1-3.

Latasse, David. 1903. Letter in Department of Indian Affairs Records. RBCM Archives. RG 10, Vol. 1343, Reel B1874, Cowichan Agency.

Latasse, David. 1932. Letter of April 4, 1932 to William E. Ditchburn, Indian Commissioner for British Columbia. RBCM Archives. RG 10, Vol. 11, 303. File 974/1-9.