Learning

- Historical significance: What and who should be remembered, researched and taught?

- Evidence: Is the evidence credible and adequate to support the conclusions reached?

- Continuity and change: How are lives and conditions alike over time and how have they changed?

- Cause and consequence: Why did historical events happen the way they did and what are the consequences?

- Historical perspective: What does past look like when viewed through lenses of the time?

- The Ethical Dimension: Is what happened right and fair?

Yesterday I posted a video from my time up in the mountains in the Tumbler Ridge Global Geopark. Today I give you a video, near that same spot, but from our new Ricoh Theta V 360 camera. Amidst all the botanizing and mushroom-hunting, I was also testing out this new tool for our online learning programs.

If you’ve never watched a 360 video before, use the circular symbol in the top left corner by using your mouse or finger (depending on the device you’re using). If you’ve got Google Cardboard or other VR goggles you can watch the video through that for an enhanced experience. Look up at the sky, look at the ground or at me swiping at bugs and using the camera controls through the app on my phone (not very exciting). Watch for my wave near the end!

Mountain Stream post

My attempt to video a sublime mountain stream without a tripod and while fending off bugs, near Bone Mountain, south of Tumbler Ridge, BC. July 24, 2018

I did not know mushrooms grew at such high elevations, but they do! While up there wandering around at about 6000 feet one of my tasks was to look for mushrooms. Mushrooms in the alpine have not been studied much at all in BC, but mycologist, Dr. Shannon Berch, Research Soil Scientist at the BC Ministry of Environment is on it. For every mushroom I found and photographed, Dr. Ken Marr took a sample, and bottled it to be sent to Dr. Berch for study.

When I’ve been in the alpine in the past, it’s mostly been on long day hikes, where I had to get up and down a mountain during daylight hours. This does not leave much time or energy for wandering around alpine meadows. But on this trip, that is all we did. We walked and walked, looking for plants for the collection. It was easy to lose sight of the others, so I had to keep reminding myself to not wander too far. Thick fogs can come in quickly in the mountains and create a difficult and dangerous situation and although we’d seen no signs of bears, we were also in Grizzly territory.

It was so beautiful up there I just wanted to keep going. Over every rise there was a new vista. There was birdsong, and far in the distance, running water coming from a stream or a waterfall, (I could not tell which but I had to get closer). That’s when (unbidden I swear) dialogue from The Sound of Music, (the part where Maria is being reprimanded by the Mother Superior for being late) came into my head. Clearly, I heard Maria exclaiming how she could never be lost up there, that these were her mountains and besides the birds were singing and the brooks were babbling and she felt like she was being called higher and higher up into the mountains. That was me that day. At one with Maria.

I mentioned my mental imagery to nearby Royal BC Museum botanists Heidi Guest. Heidi in the mountains with (I kid you not) braids in her hair. Being a good sport, Heidi, spontaneously swung her plant collecting gear around her not unlike Maria while singing I have Confidence. I’m telling you it was a moment.

What I was surrounded by up above the treeline:

What I spent most of my time looking at:

Dr. Ken Marr is Curator of Botany at the Royal BC Museum. I ambled with Ken (botanists amble) last month while he was out collecting plants in the mountains south of Tumbler Ridge.

Mountain Excursion – Post #2

Okay, I don’t even know what to tell you about these photos. I only know that there are fossils in every one of them. There are fossils everywhere in the geopark. They were incredibly distracting! I was to be taking 360 video, botanizing and mushroom hunting (more on that in a future post), but kept happening upon these rocky wonders and wanted to just sit down in front of them to look. So I snapped pictures when I could.

Also, we had no paleontologists with us or identification guides. Have a look at the pictures and wonder with me, or if you are in the know, please comment!

Mountain Excursion image

Last wee k I went where few British Columbians go: the high alpine in our spectacular Northern Rockies. When at the last minute one of the Royal BC Museum scientists could not make the trip, I had the good fortune to take her place in the helicopter and spend two days in the field with a small team of museum researchers. My purpose was to bring back photographs and videos for our online learning programs, (especially with our new 360 camera) and to use my naturalist skills to help the botanists collect plants.

k I went where few British Columbians go: the high alpine in our spectacular Northern Rockies. When at the last minute one of the Royal BC Museum scientists could not make the trip, I had the good fortune to take her place in the helicopter and spend two days in the field with a small team of museum researchers. My purpose was to bring back photographs and videos for our online learning programs, (especially with our new 360 camera) and to use my naturalist skills to help the botanists collect plants.

On July 23rd, the helicopter dropped us off about 40 kilometres south of Tumbler Ridge in the Global GeoPark. It was glorious. I took so many photographs I’ve decided to blast you with a series of short photo-posts over the month of August! (It’s like being stuck at a friend’s home movie night, except this is optional and hopefully you won’t feel stuck, but awed by BC’s beautiful and biodiverse northern alpine).

Royal BC Museum field camp tents near an alpine lake.

Alpine flowers including anenomes gone to seed or ‘hippies on a stick’ as they are affectionately and aptly known.

Terry Fox and Family post

Right now at the Royal BC Museum, Family: Bonds and Belonging is running concurrently with Terry Fox: Running to the Heart of Canada. The two exhibitions stand side by side. This is personally fitting to me because I have long associated my grandfather with Terry Fox, and there is a photograph of me with my grandfather in the Family: Bonds and Belonging exhibition.

Here’s how I have linked them in my mind: Terry Fox started his run on April 12, 1980 in Newfoundland. One year before on April 12, 1979, ‘Gramps’, a Newfoundlander, died of cancer. So when Terry dipped his leg in the Atlantic off the east coast of Newfoundland, it seemed extra meaningful to my adolescent mind.

Terry’s story unfolded when I was an impressionable teenager and like millions of Canadians at the time, I was riveted by his story. Plus, he was from Port Coquitlam, just across the Fraser River from where I lived in Langley. We were practically neighbours. Like most of BC’s Lower Mainland, we felt like Terry was ours.

I remember imagining what it would be like if Terry made it over the mountains and down into the Fraser Valley. But as we all know, that day didn’t happen. In BC, we never saw the van up close. But now we can.

If you remember Terry Fox, like I do, it’s compelling and moving to peer inside the van that is parked just inside the Royal BC Museum lobby. It’s not so hard to imagine him there: A sweaty, young athlete with an astounding will.

Terry Fox van in the Royal BC Museum lobby.

When I watched Terry’s van being pushed into the Royal BC Museum before the exhibit opened, even though I knew it had been rebuilt and fixed up and a punk band lived in it for years, it still felt real. It still felt like a return. A homecoming. It felt important.

Like a lot of Canadians, I remember the terrible day that Terry’s run ended. I remember watching his heartbroken mom and dad at his side on TV as he was loaded into an airplane to fly home. I remember well the day Terry died. And after all these years, I can still not get over that he ran a marathon a day, for months, on one leg.

There’s nothing like an indisputable hero in your midst to make you feel inadequate. That sounds cynical. I’m not trying to be cynical. I think Douglas Coupland said something like ‘It’s impossible to be cynical about Terry Fox’. I think this is true. Terry’s accomplishments are so exemplary, so astonishing, so inspiring, that I am humbled by what he accomplished and what he has done since he died. I don’t feel less around his legacy, I feel in awe, inspired, hopeful.

Where I feel inadequate is in my everyday habits at the Royal BC Museum while the Terry Fox exhibit is here. There’s nothing like our every day routines to put us on autopilot. Every morning since the exhibit opened in April, I’ve walked past Terry Fox’s van on the way to my desk. Terry Fox’s van. At first I couldn’t look at the van without a lump in my throat, and now I often rush past it like it’s nothing.

Which it’s not.

Terry’s incredible story lives with all of us who remember him and it is here now at my museum in his van, in his running shoes, in the thousands of letters children wrote to him and it lives in that jug of Atlantic Ocean he scooped up that first morning in April 1980. The jug of water right now sitting not far from a photograph of me with my Newfoundlander grandfather. The Atlantic Ocean on exhibit and in my veins. Terry Fox and Gramps, their proximity here on the Pacific coast, making this big country feel small and close.

The jug of Atlantic Ocean water from the first day of Terry Fox’s Marathon of Hope in the Terry Fox: Running to the Heart of Canada exhibition.

At museums we often talk about objects telling stories. For me this summer, the objects in these exhibitions tell me to slow down and remember that there is sacred in the every day. Until the Fox exhibition closes in October, I’ll try not to rush past the van on the way to my desk.

CETA 1972 style post

While working with archival documents it is always of interest to look at the other side of the page.

In today’s example, A person needed to publish several legal notices in the local paper.

Luckily, the entire newspaper page was submitted.

The following article appeared on the back of the page (The Province [Vancouver], Friday, 10 November, 1972.)

It describes how Pacific Western Airlines was able to ship live beef to Europe, because its cargo plane could return with a cargo of grapes which were now available throughout BC and Alberta.

The article also explains how the plane was cleaned, presumably before the grapes were loaded on to the plane.

The Wikipedia page for PWA mentions the following:

Boeing 707 equipment was added to the fleet in 1967… The addition of a cargo model Boeing 707 meant that livestock and perishables could now be carried all over the world, and the name Pacific Western became synonymous with “World Air Cargo”. The company aircraft visited more than 90 countries during this period of time.

Pacific Western operated a worldwide Boeing 707 cargo and passenger charter program until the last aircraft was sold in 1979.

This is in the era where container shipping was beginning its world wide adoption.

Air cargo was expanding during this time as well, when “Boeing launched the four engine 747, the first wide-body aircraft” in 1968.

As the newspaper report explains, transportation of people and goods only makes sense if the airplane is loaded to maximum capacity at all times.

This was the thinking behind the Triangular trading system of the 19th century.

Moving people extended this thinking to modern day hub airports such as Toronto Pearson, London Heathrow and Dubai UAE.

Even today with airplanes that can travel half way around the world, the take off and landing locations are the national hub airports.

Air cargo has undergone the same thinking.

In the 1972 news report, it only made sense to Pacific Western Airlines to undertake this one-off trip once the entire route was fully booked.

The article goes on to describe how the airline was looking for other opportunities. They recognized the potential, but the tipping point (the development of an airport hub for cargo) had not yet arrived.

To see what kind of completion PWA would face today simply go to an airplane tracking app and filter for FedEx planes, or track the Memphis airport.

UPS has a similar hub in Louisville. Here is an example of one airplane in the UPS fleet that revisits the hub city regularly. This particular plane left Louisville on 28 May 2017 and travelled around the world via Honolulu, Hong Kong, Dubai, Cologne, and Philadelphia, before returning to Louisville three days later.

When you read this article, there will probably be more recent examples of round the world trips or forays to Asia or Europe before returning to it’s home base.

The article does not quote anyone from the BC Livestock Export Association, however Europe is again front of mind for the Cattlemen’s Association.

Mr. W. Allan Eadie produce manager for Woodward’s, and PWA cargo specialist Ken Bjorge would be impressed!

As Mister Eadie says in the report, he hoped that this operation would expand because of “this cattle thing.”

He and Mister Bjorge may have failed to realize that the problem was not to solve the “cattle thing.” They needed to solve the “hub thing.”

On a side note, The Imax movie “Living in the Age of Airplanes” has an excellent section on the transportation of flowers that is well worth the price of admission.

PWA purchased CP Air to form Canadian Airlines International in 1987.

Canadian Airlines has the distinction of being the first airline in the world to have a website on the Internet (http://www.cdnair.ca/).

It merged with Air Canada in 2001.

Outreach for Seniors download

Understanding how Museum Outreach can Impact the Social Well-being of Seniors Living in Care Facilities in British Columbia

Using a mixed-methods approach, this study compared the effect of two museum outreach programs. A reminiscence themed outreach program (the recollection of life stories prompted by objects) was evaluated against the effect of a new learning theme outreach program (participants work out the purpose and function of mystery objects through observation and discussion). The kits were delivered by trained facilitators from the Royal British Columbia Museum (Royal BC Museum) to six groups at four care homes in the Greater Victoria area. Participants, seniors (65 years and older) living in the care homes, did a pre- and post-test to measure mood, and observations were made during the program using field notes and audio recordings which were later analyzed for evidence of socialization. The results found that both types of programs improve mood and both offer opportunities for socialization, however the success of the reminiscence program is more dependent on the skills of the facilitator.

I ran across an interesting video of describing how a Museum is using its food offerings to integrate them with the rest of the museum experience.

The item appeared as part of “CBS Sunday Morning” food edition on 20 Nov 2016.

Here is the link.

The menu recreates historically famous items from around the world as taught to the staff by the chefs who created them.

This is the link to the menu.

The menu includes the name of the chef, the restaurant, city, and year of creation.

Be sure to click through the Lounge, Dining Room and Beverage tabs!

One of the dishes created there is Oops! I dropped the lemon tart.

Three-Michelin-star chef Massimo Bottura’s describes how the dish was created here.

Feel free to research the chefs, restaurants and recipes listed on the menu. Time well spent!

View out the classroom window from the Museum of Vancouver

Attending the Historical Thinking Summer Institute at the Museum of Vancouver was mind-blowing for me on several levels, least of which was that my youthful association with the location.

Back in the day, the site’s most prominent inhabitant, The Planetarium, was known far and wide to teenagers all over BC’s lower mainland as the place to see the ‘star show’, which entailed some kind of animated replica of galaxies projected onto The Planetarium’s ceiling. The entire experience was accompanied by Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon.

These days, The Planetarium operates quite independently of the museum and has been renamed H.R. MacMillan Space Centre and the Museum of Vancouver stands on its own as an important cultural player in the life of Vancouver, despite people like me who still associate it with Pink Floyd.

But no more. After attending the Summer Institute, I can report that I now associate the site with more than Pink Floyd. I was at the Summer Institute to deepen my understanding of historical thinking concepts, a framework for teaching history and creating learning experiences about history, that we are already applying to programming at the Royal BC Museum.

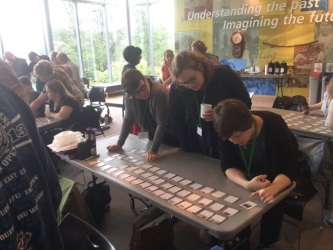

Historical Thinking Summer Institute participants prioritizing events in Canadian history and exploring the question ‘What is historically significant and who gets to decide?’ Photo credit: Lindsay Gibson

What are historical thinking concepts?

Historical thinking concepts are essentially the framework that historians use to construct history, broken into distinct elements to help students think about the process. Recently retired University of British Columbia professor Peter Seixas and veteran teacher Tom Morton have presented the historian thinking in their aptly named book The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts. The ideas in this book have been widely applied to curricula across Canada and particularly to BC ‘s new social studies curriculum.

The historical thinking concepts are:

(From: Thinking Historically Reference Guide)

Scientists use scientific methods to reach their conclusions. Historians use historical thinking concepts to reach theirs. Unlike in science education, in history classes there has been little to no emphasis on how historians work. Using historical thinking concepts shifts the focus from content, the events of history, to instead the process and issues that historians grapple with in their work.

Teaching history from this perspective brings history classes to life in a very practical way. Learning to think like an historian is about learning to think critically. Critical thinking skills are a key part of 21st century learning, the foundation for BC’s new K-12 school curriculum. As one of my classmates put it, historical thinking concepts are life skills.

During the Summer Institute we left the classroom for two enriching field trips. The first was to the Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site and the second was a walking tour of Vancouver with John Atkin. Both excursions gave us the chance to see historical thinking concepts exemplified. At historic sites and in history tours, just like in creating museum exhibitions, decisions are made about which historical narratives to present. It was useful to experience the fieldtrips with the lens of historical thinking and discuss with classmates while we were deep in our exploration of the concepts.

On the final day of the Historical Thinking Summer Institute, we presented our group projects to each other. It was inspiring to be in a room with all that passion and brain power. One of my classmates, Vancouver teacher Craig Brumwell, posted about the Summer Institute on his blog here.

Back at the museum, there is much relevance to our work in the learning department. Programming ideas are percolating that will complement BC’s school curriculum and enrich online materials on the Learning Portal and for our new Digital Fieldtrips. The Summer Institute confirmed for me that we are on the right track with our Learning Portal and other online resources. Teachers want to use primary sources as historical evidence in the classroom. We already provide these digitally through the Learning Portal, 100 Objects of Interest and Transcribe sites. We will continue to add digitized copies of primary sources such as photographs and letters to these sites. In the Learning department, we will continue to reach out to schools across the province to connect them with the learning materials and experiences they need.

Personally, I will reflect on the the historical thinking concept continuity and change and leave Pink Floyd out of it.

(The Critical Thinking Consortium has a series of short videos to introduce historical thinking concepts to teachers and students here.)

Teacher Takeover post

On June 23, 2016, students from the University of Victoria’s department of Education partnered with our Learning Department at the Royal BC Museum for a gentle takeover of the museum galleries. The goal was to look critically at the existing galleries, and ask the questions ‘where do I fit in, and what can I actively do to make for a more inclusive space?’

Sarah Lazin, a Learning Program Facilitator at the Royal BC Museum, came along to see what was going on, and this is her report:

A raggedy bear with no eyes. Two pairs of dancing shoes. A roll of hockey tape.

Items with no obvious value or relationship were carefully grouped together and labelled, resting upon tables that had been turned into makeshift museums. A group of fourth-year education students from UVic circled the displays, adjusting their exhibits and reading out the backstories crafted for each artifact.

They arrived at the museum, slightly confused by their instructions (or lack thereof). Each person had brought with them an item of personal significance – but why would a well-loved teddy bear be of importance to the provincial museum?

After spending time in the galleries, their task became clear. The students were to intervene in the museum’s way of storytelling by adding or taking away from the exhibits. They could use the items they brought to tell new stories, though they weren’t required to. Their interventions revolved around central questions that struck them during an exploration of the Human History floor.

“Where is the science section?” One group asked. “And where are the women?”

Another group noted the lack of music and of people.

“Where do immigrants fit in? Where do I fit in?”

The museum had long since closed to visitors; these questions reverberated throughout each room. The students broke into groups based on which of these questions resonated with them the most. They dispersed into the gallery, armed with empty photos frames, markers, and curiosity.

Some interventions were bold: one group donned suspenders and caps, and would perform tap and swing dance routines for visitors passing by – adding a human element to the gallery they felt was sorely needed.

Others were subtle: one group decided to offer visitors a choice as to which photograph should replace an out-of-place piece of art. Another group hung photos of the LGBTQ community from each decade from 1900 to the present alongside that decade’s respective fashion display, fighting the systematic erasure of certain groups.

Theodore, the teddy bear, found himself left on the gallery floor, covered by a plexiglass case. The story of a migrant family, written in both English and Spanish, reminded visitors of the exhausting process of leaving everything behind in search of a new home, and everything that was lost or left behind in doing so.

After working on their interventions well into the night, the students headed home. They returned early the next morning, to put the finishing touches on their projects and prepare themselves for the waves of approaching visitors.

The museum opened and so the students waited. Slowly at first, visitors trickled into the gallery, unaware that the students were listening to their conversations and gauging their reactions to the interventions.

Some stood to facilitate their projects: one group dressed as scientists and challenged preconceived notions of gender and ‘appropriate’ work in decades gone by. This group, among others, asked questions to visitors, explaining why they were in the museum and gathering feedback directly.

Other interventions stood alone, posing questions for visitors to think about as they wandered through the gallery.

At 11am, the interventions quietly disappeared. Suspenders and caps were removed, photographs were taken down. The soon-to-be educators left the museum as they had found it, chatting to each other about unconventional storytelling, disrupting hegemonic accounts of the past, and the value of alternative educational spaces.

Fun vs. Educational post

At this time of year, many of us are looking for presents and if you are like me, you might be debating should you buy something fun or something educational? This kind of question comes up all year round when you work in a museum or science centre and you are developing interactives and you consider in the use of ‘interactive’ are we privileging the physical at the cost of the intellectual and emotional?

Pine and Gilmore (1998) define experience as something that is memorable and personal. Memorable and personal experiences are those that include high levels of customer participation and the connection. In addition, “experiences, like goods and services, have to meet a customer need; they have to work; and they have to be deliverable” (Pine & Gilmore, 1998, p. 102).

If you switch the word “audience” for “customer” could this be the mission for the public program department at a museum? The use of the physical can go hand in hand with the development of the intellectual and emotional. Roth and Jornet (2014) concur when they write “ experience … integrates the physical-practical, intellectual, and affective moments of the human life form that interpenetrate each other” (p. 106).

The best way to integrate the physical within the museum is by the use of interactives. “Museum exhibits not only engage visitors and help them to construct meanings, they usually also reference the larger world of cultural subject knowledge. The represents the part of the component that Dewey called ‘interactivity’, which… has breadth and depth and needs to be considered in discussing experience” (Hein, 2006, p. 193).

In his description of a museum interactive, Shea (2013) urges us not to sacrifice entertainment for education when in fact “enjoyment causes the visitor to positively engage with the objects and therefore to develop an interest in learning about the technology that makes them work, producing a desire to discover just how exactly they do it”. This quest for meaning-making is what Roth and Jornet (2014) emphasize about Dewey’s (1938) definition of experience when they say “the most important among the attitudes to be developed in and through experience is ‘the desire to go on learning’” (p. 116).

Having fun at an interactive does not automatically diminish the potential of educative experiences, if anything, it is an important ingredient.

References

Pine, J., & Gilmore, J. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76(4), 97–106.

Hein, G. (2009). John Dewey’s ‘wholly original philosophy’ and its significance for museums. Curator, 49(2), 181–203.

Roth, W.-M., & Jornet, A. (2013). Toward a theory of experience. Science Education, 98(1), 106–126. doi:10.1002/sce.21085

Shea, M. (2014). The hands-on model of the internet: Engaging diverse groups of visitors. Journal of Museum Education, 39(2), 216–226.

Thanks to my UBC Masters of Museum Education cohort for asking this question. Learn more about the Masters of Museum Education at UBC here Applications for 2016 close in March.