Research

When is a holotype not a type specimen?

When it was never published in the first place.

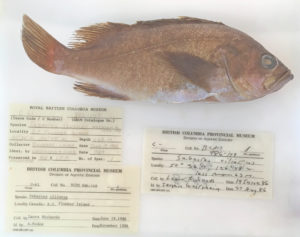

The Royal BC Museum fish collection contains a specimen which had been locked securely in one of our type cabinets since the 1980s. It was designated as the holotype for a new species – Sebastes tsuyukii – there was even a manuscript noted on the specimen label (Westreim and Seeb 1989). It sounded legit – and no one checked until recently.

Jody Riley – my ever diligent volunteer – flagged this record when she was re-organising the fish collection. She checked what is in our old paper catalog, checked the electronic database, then looked to see if the actual specimen exists. When Jody hit Sebastes tsuyukii, and found no record of the species online, yet here in her hands was the jar with a big yellow tape label saying Holotype for Sebastes tsuyukii, she knew something was fishy.

Did the manuscript stall during composition, submission, or revision? Who knows.

In the end, we can take this large jar out of the cabinet designated for type specimens, Sebastes tsuyukii now is a nomen nudum (a naked name), and I can delete the species from the taxonomy in our museum database. Some database problems are easy to solve.

But this reminds me to get my fingers in gear and type the type descriptions for species I have yet to publish.

Last year I came across an interesting document. It is a Memorandum of Cooperation between British Columbia and the State of Washington and was signed in July 1972 by Premier W.A.C. Bennett and the Governor of Washington, Daniel J. Evans. It is a simply written two-page document outlining the desires of both parties to protect the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Strait of Georgia, Puget Sound and their adjacent waters from oil spills.

The document came to the BC Archives in 1973, from the Office of the Deputy Provincial Secretary and had been stored offsite with just a control number.

I rehoused it and made a descriptive record and recently our preservation team scanned it at my request. Now anyone can read the document by clicking on the image and downloading the pdf, GR-0160

Along with some 1977 photographs of oil spill experiments, it offers a glimpse into some of the prevailing issues in that decade.

I-20083

I-20081

I-20086

Orca Abscessed post

Nitinat (T12A) was a well known Orca along the BC coast. Born in 1982, he was a fixture along the BC coast and an active participant in the 2002 attack on a Minke Whale in Ganges Harbour, Saltspring Island. This animal – with its characteristically wavy dorsal was found dead off Cape Beale near Bamfield, September 15th, 2016. Funds weren’t available to prepare the entire skeleton, so I had to settle for the skull and jaws.

As you can imagine, the head of an orca would pop the frame of any domestic chest freezer, and it blocked the aisle of the walk-in freezer at the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo. It was also no small feat to fork-lift the head into the museum’s van, and then get it back out of the van and wheel it to the museum’s walk-in freezer. It also was a surreal experience driving around with an orca head in the truck. The head is heavy – and slippery – and difficult to tie down – so I drove smoothly to avoid having the head roll around behind me. Imagine explaining to an insurance company how an orca head caused you to lose control of your vehicle?

Nitinat’s head was prepared by Mike DeRoos and Michi Main – their internationally acclaimed business, Cetacea, focuses on cleaning and articulating whale skeletons. While preparing this skull for burial, they noticed that Nitinat had broken teeth. Given that I broke a molar on a frozen Reese’s Piece in a Dairy Queen Blizzard, I could imagine how Biggs Orcas could break a tooth when biting down on a sea lion or elephant seal. Large pinnipeds have dense bones.

Once the skull was cleaned, Mike and Michi found that not only were teeth broken, there also is a nickle-sized hole in the palate and many teeth were abscessed. The hole in the palate is particularly interesting. It has smooth sides and so certainly had healed before Nitinat’s death. Was it a puncture and the source of the infection that caused the distortion of the teeth? Or was it a channel for the abscess to weep into Nitinat’s mouth (not a pleasant thought regardless).

Normal teeth (left) have a long root and recurved crown, with natural wear for their ecotype – but the abscessed teeth were stunning with their broken crown and expanded root. They almost remind me of some squash varieties that are available.

One of the teeth is so swollen that it couldn’t be removed from its distorted socket.

Red lines beside the skull indicate expanded tooth sockets – perhaps age and infection combined to create this effect. The sockets for the abscessed teeth were eroded and far larger than normal sockets (in this non-mammalogist’s opinion). Erik Lambertson made a great scale bar.

Nitinat’s teeth are enough to make anyone who has had a toothache cringe, and a dentist’s eyes pop with fascination. I am just waiting for the day someone requests to see Nitinat as the focus of a pathology research paper. For now, he is a permanent addition to the Royal BC Museum collection and will soon get his official catalog number.

I don’t know if the title of this article is an accurate way to say fork-tailed lizard in German, but the Gabelschwanz-Teufel – the P-38 Lightning (the fork-tailed devil) could take a lot of punishment and still get home at the end of a sortie. A fork-tailed lizard has a parallel story – it has taken a beating and survived.

It is common to find lizards with regenerated tails or tails that are recently dropped – with their tell-tail stump. Sometimes the tip is lost, others about 90% of the tail is lost. The regrown tail segment is never as nice as the original and has different scale patterns and colouration.

This male Wall Lizard photographed by Deb Thiessen, lost its tail near the base and the regenerated tail is obvious. Its meal had a perfect tail.

I have seen fork-tailed, even trident tailed lizards in photos – I remember images like this in the books I poured over earlier in my ontogeny. Had I ever seen one in person? Not until now. During my PhD thesis work, the only fork-tails I thought about were thelodont fishes known from Early Devonian rocks of the Northwest Territories.

This July, Robert Williams, a colleague from University of Leeds in England was here working on Wall Lizards. He was trying to determine if our native Northern Alligator Lizards react in any way to the scent of the European Wall Lizard.

Live animals are not allowed at the Royal BC Museum, so Rob had to perform scent trials in my dining room. The lizards were held in containers in my kitchen – and I thank my wife for her patience.

The work helps give a frame of reference to reactions between the native Sand Lizard in the UK and introduced Wall Lizards, but you’ll have to wait to hear the results. While hunting Wall Lizards on Moss Rocks here in Victoria, Rob caught a fork-tailed specimen.

Since this was such a neat specimen I requested it be saved intact for the Royal BC Museum’s collection. Here is a photo of a fork-tailed Wall Lizard from England, but Rob had to come all the way to the Pacific coast of Canada to catch one.

Lost Soles post

In museum collections, space is critical. We can’t waste space. Every millimeter of shelving is critical. If you can arrange cabinets more efficiently, do it. Can you pack more jars in a given area? Do it. If you can make space. Do it.

I have been on a binge of deaccessioning lately. What is deaccessioning? It is the museum practice of removing accessioned/cataloged specimens from the collection. Once deaccessioned, we either send specimens to other museums where they are relevant, or give them to teaching collections or perhaps to nature centers. Only rotten specimens are destroyed. We try everything we can to re-purpose specimens before we resort to destruction.

This surfperch, Embitoca lateralis, is a rare candidate for destruction. It has been deaccessioned – someone had cranked the clamp too tight years ago and the glass at the apex of lid popped. Alcohol evaporated and by the time it was noticed, it was too late. If the fish in the jar could speak, they’d say, “There’s a fungus among us.”

Deaccessioning allows me to make space in the collection for new material. Since I am trying to keep the Royal BC Museum’s vertebrate collection focused on British Columbia, the eastern North Pacific Ocean and any adjacent territory, specimens with no relevance to this region obviously have my attention. Specimens with incomplete information (or no information), also flare my obsessive nature and are on my deaccession hit list. Space is created on a jar-by-jar basis.

Putting ‘incomplete information’ in everyday terms – if we are going to meet somewhere, you generally expect some level of detail. If I say I want to meet in Tofino in June, what would you say? Imagine now that I didn’t even give you my name – but still wanted to meet in Tofino in June. I am betting you’d put on your best Monty Python-esque King Arthur and say, “You’re a Loony.” Incomplete or missing data is a real issue.

My long suffering volunteer Jody found a jar of flatfish this weekend which had never been cataloged, but was in the collection. It was only a 125 ml jar – so not a huge waste of space. On closer inspection the fishes were identified (Parophrys vetulus, English Sole), there was a location (Tofino), and a date (June 1985).

Where was I in June 1985 – oh yea – just about to graduate from grade 12. Oh the 80s – I am listening to Duran Duran while typing this – RIO – the obvious choice with its maritime theme.

Yep, that was me in 1985.

Parophrys vetulus is a common fish here in BC, so it is likely you can catch them all around Tofino in June – but it would be nice to know which beach relinquished its sole. And when did it happen? Was it at night? Was it a full moon? On the 1st of the month, or mid month? Were they in ankle-deep water or at 10 meters depth? Open beach or a tidepool? Caught by hand or with a net? Inquiring minds may want to know. And with no collector noted in the hand-written label – I can’t even badger someone by email to jog their memory or review old field notes.

These are the lost soles Jody found. Is one of them yours?

To a museum, data is everything. If you collect and preserve a specimen, record as much as you can about the event. If you are giving me your sole, then tell me its secrets.

Ship pics post

Don’t say that too quickly.

I recently enjoyed looking through an old photograph album that was given to the Provincial Library and Archives in December 1937. The album was donated by Major Harold Brown, Managing Director of the Union Steamship Co. Provincial Librarian W. Kaye Lamb noted that the photographs were probably taken around 1924-1925.

We don’t know why Brown created the album, maybe it was useful to have photographs of the Union Steamship Co. ships (and others) to hand when doing business.

Over the years we have scanned about 147 of the 250 photographs in the album. They can be viewed online with their description MS-3079.

I am interested in the ones that show some kind of port activity like this one of the tug Helac and the Kaga Maru at what looks like the Vancouver Harbour.

But this one is quite sad, it’s the Toyama Maru in Vancouver Harbour. Twenty years later it would be sunk by the USS Sturgeon, killing over 5000 Japanese soldiers and sailors.

Saturday was International Archives Day. This year’s theme is Governance, Memory, and Heritage. It’s a broad subject, but it really covers the essence of what we do.

Part of my job involves giving tours of the BC Archives, often to groups of people that have never used an archives or considered doing archival research. In my 10 minute “Archives 101” introduction I start with one of the main tenants of why we keep records: because archives are a mainstay of democratic governance. Embedded in democracy is the right of the people to access information about themselves and their government. In theory we keep about 5% of all the records created by government, but that small percentage should capture the good stuff: decision making documents, policies, annual reports, and other summary records that illustrate what a particular government office was doing at a moment in time.

Government records are great for giving an overview of society, but they can be somewhat dry – and so much of society operates outside of government. For this reason, the BC Archives long ago adopted a “total archives” approach, seeking to fill in the gaps in the record by acquiring the records of individuals, families, businesses, and organizations whose impact was provincial in scope. Of course, deciding what records fit this mandate is subjective, and institutional interests or priorities can be evident in collecting practices over time. Ensuring that the spectrum of humanity and experiences in BC are reflected in the archives is a challenge, and we must continually evaluate the work that we do, recognizing that there will always be silences in the record, and that often what we don’t find in the archives is as important as what we do find.

One thing you can be sure to find in the archives is variety. From the people and the places described, to the format that the information is found, there is more to the archives than most people expect. A record is any recorded information: textual (written records), cartographic (maps, plans, architectural drawings), audio-visual (sound recordings and moving picture recordings), graphic (photographs, paintings, drawings and prints). For International Archives Day, we wanted to highlight a few of our diverse collections. But how can we choose among the thousands of series? I’ve selected a few today, but the @BCArchives twitter account will continue to highlight our records by tweeting a “Featured Collection” twice a month from now on. Although some of what we share may have restrictions on access, we hope they give a sense of the fascinating information found in the stacks at the Archives!

FEATURED COLLECTIONS:

GR 3571 – Premier’s Correspondence. 131 m textual, photos, audio, ephemera. These records cover the period from 1974 to 2008 and document ordinary peoples’ reactions to “hot topic” issues of the day such as old growth forestry logging, RCMP officers wearing turbans, the tainted blood scandal, and government funding of AIDS medication. Included are some children’s letters and art from school groups. This collection is may have some restrictions on access.

PR-2086 Philip Borsos fonds. 22 metres of multimedia material including film reels, magnetic tracks, optical tracks, optical discs, video reels, videocassettes, audio reels, audio cassettes, audio compact discs, photographs, technical drawings, maps, prints, production boards and computer disks. Borsos was a filmmaker with a career spanning 1970 – 1995. The film projects chronicled include the documentary shorts “Cooperage”, “Spartree”, “Phase Three”, “Nails”, and “Racquetball”, and the features “The Grey Fox”, “One Magic Christmas”, “Bethune”, and “Far from Home: The Adventures of Yellow Dog.” The fonds also includes Borsos’ journals and miscellaneous personal papers.

GR-3377 – Provincial Archives of British Columbia audio interviews, 1974-1992. Consists of 440 sound recordings. The series consists of oral history interviews recorded by staff members and research associates of the Provincial Archives of B.C. Major subject areas include: political history (especially the Coalition era, the W.A.C. Bennett years, and David Barrett’s NDP government); ethnic groups (including Chinese- and Japanese-Canadians); frontier and pioneer life; the forest industry; B.C. art and artists; the history of photography, filmmaking and radio broadcasting in the province; and the history of Victoria High School. This is one example of many oral history collections at the Archives!

GR-0419.34A – Attorney General documents, 17 (1887). 235 pages. File includes correspondence and other records relating to the so-called “Kootenai Uprising.” Records describe the dissatisfaction of the Ktunaxa with their assigned reserve lands; the accusation of two Indigenous men of murder, followed by the arrest of one called Kapla, and his subsequent escape with the assistance of Chief Isadore; and the deployment of the North-West Mounted Police, led by Sam Steele, to the region. Of particular note is a verbatim transcript of a speech delivered by Chief Isadore in July 1887.

PR-1380 – Frederick Dally fonds. 7 cm of textual records, 466 photographs, 1 map. Frederick Dally was born in Wellingborough, Northamptonshire, England in 1840. He arrived in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1862, on the China Clipper “Cyclone.” In March 1864, Dally leased a store at the corner of Fort and Government streets, and in 1866 he opened a photographic studio in Victoria. Between 1865 and 1870, he took extensive photographs around Vancouver Island and in the Cariboo District.

Lacertophagy post

I have said before that European Wall Lizards (Podarcis muralis) will eat smaller conspecifics – there are a few photos online from elsewhere on Earth – but until now I didn’t have solid evidence of lacertophagy (lizard eating) here on Vancouver Island.

However, this last week, Deb Thiessen took a few videos of a Wall Lizard eating a yearling Wall Lizard on her property just north of Victoria. These are really good videos and clearly show that Wall Lizards can stuff down a huge meal.

https://www.facebook.com/deb.thiessen.9/videos/10214455524975688/

In this first video the smaller Wall Lizard is already dead, and I suspect that the larger lizard killed it. Looks like another lizard had thoughts of stealing the meal. Sure looks like breathing is an issue while stuffing down so large a meal. Snakes solve the problem of eating and breathing by pushing their trachaea (windpipe) out of the mouth so that food does not block air flow.

https://www.facebook.com/deb.thiessen.9/videos/10214455487814759/

The victor looks like a male, and in the second video you can see how quickly it disposes of the tail rather than having that part of the meal hanging out of its mouth for a few days.

Almost all of the victor’s own tail had been lost some time ago. You can always see where its original tail ended and the re-growth takes over – the new tail is never as neatly patterned.

Be glad Wall Lizards aren’t the same size as Varanus prisca, otherwise we’d be on the menu.

Last summer I worked with some really interesting records that illuminated the “Home Front” situation in British Columbia during World War 2.

Activity, particularly in the realm of Air Raid Precautions (ARP), was a curious mixture of official and civilian partnership. In 1942 Premier John Hart formed the Advisory Council, Provincial Civilian Protection Committee to assist and advice the official Provincial committee in the organization of air raid precautions in the province.

The Advisory Council took on a lot of administrative work in distributing grants to BC communities to buy equipment, train volunteers and disseminate information.

The records of the Committee are with the BC Archives and are described as GR-0268. Last year I found three boxes of missing records and added them to the series. The series description can be viewed here.

The records are open for access but are stored offsite so can take a few days to bring in.

There are also some photographic records created by the Advisory Committee which I had a lot of fun working with. One series, GR-3644, consists of 77 b&w photos of ARP activity. Our preservation unit has scanned these so they can now all be viewed online.

Some of my favourites include I-78009 (children learning to use respirators), I-78029 (volunteers receiving training), I-78002 (recruiting poster) and I-77973 (gas decontamination crew during practice)

Science is Serious post

Or if you are an astronomer, then your science is Sirius. If you are a geologist, then your science is pretty gneiss. Don’t take science for granite.

I have been tracking Wall Lizards now for a while – and I am sure my wife will say lizard tracking has become an obsession – a serious obsession. I look at rock walls as we drive around town. I look for lizards on our weekend hikes. I watch for lacertids when I walk our daughter too and from school. Science is serious.

I have been watching the range expansion of two nicely segregated populations of lizards in Victoria – one population is about 0.63 km SSW from our house west of Hillside Mall, and the other is about 0.24 km north of us near Doncaster School – not that I have measured.

Each year I walk the perimeter of these populations to get an idea how fast lizards disperse in urban environments – again – this is serious science. Stop laughing. I can hear you laughing. Rolling your eyes does not help.

Wall Lizards seem to spread 40 to 100 meters – and it is the young ones that do the dispersing. Why? They race off to new habitat to avoid the cannibalistic tendencies of their parents. Parents with a 40 year old trekkie in the basement may want to consider this option as an incentive to get kids to move out.

Young lizards head for the relative safety of boring lawns – garden areas with lots of structure are occupied by hungry adults. Homeowners sometimes claim their lawn is crawling with young lizards in August – when all the summer’s eggs have hatched. In contrast, adults are relatively sedentary – once they find good sunny, rocky (complex) territory, they tend to move very little from year to year.

Now imagine my surprise when I walked up my driveway last night (May 23rd, 2018) and heard the characteristic rustling sound of a lizard in our food forest (yes, the lawn is gone and we have a food forest – the entire front garden is devoted to plants we can eat, and plants that attract bees to pollinate the plants with edible bits – but I digress). The lizard I found is at least 0.24 km from the nearest known population of lizards in my neighbourhood, and is an adult – with a perfect tail too – must have lived a charmed life free of bird and domestic cat attacks. Did this adult go walkabout? I doubt it.

The new colonist in the food forest at UF1510 (yes, as sci-fi nuts we gave our place a code name Urban Farm1510)…

Furthermore, the lizards nearest to my house are not brightly coloured – in fact they are kind of drab as far as Wall Lizards go. But our new lizard is gorgeous – more like ones from Triangle Mountain or farther north on the Saanich Peninsula.

This male is from Durrance Road – far more colourful than the ones near Doncaster School or Hillside Mall.

Is this a case of seriously good science prank? Was this a drive-by lizarding? Did a neighbour just buy some new garden supplies and a stow-away lizard emerged to find utopia in our food forest? I may never know.

My daughter has named the lizard Zoom. I guess he is there to stay.

Here’s a link to a new paper by: Luke R Halpin, Jeffrey A Seminoff, and myself.

Source: Northwestern Naturalist, 99(1):73-75.

Published By: Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology

This new paper provides the first photographs of a Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta) from west of Vancouver Island. The species has been spotted in the region before and as far north as Alaska, but until now, there were no photographs or specimens as solid evidence.

While the photos in this paper are black and white – the original photographs by Luke Halpin are color and van be viewed upon request. PDFs also are available – just send me an email.

British Columbia is now within the range of 4 species of marine turtle. This Loggerhead survived into February of 2015 because of the unusually warm water in the eastern North Pacific Ocean (the Warm Water Blob), whereas Green Sea Turtles (Chelonia mydas) and Olive Ridley Sea Turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) wash up dead (or near dead) in early winter. Unfortunately, the fate of the Loggerhead from 2015 is unknown.

Nanaimo Invasion post

Years ago after coming off parental leave, I found a series of photographs of Wall Lizards and a Google Earth image of a road intersection marked to show locations for a lizard colony. Quick search in Google Earth showed that this colony was in Nanaimo. I fired off a fast blog article to generate interest and get people looking for Wall Lizards.

It worked. Reports came in.

Jump forward a few years and now that street (Flagstone – site 1) is crawling with lizards according to eyewitnesses. But we now also have another site (2) along the Nanaimo Parkway near Douglas Avenue and Tenth Street. Oh wait, there’s also a third site (3) in the Chase River Estuary Park, and as of this weekend, there’s another (4) – way north of the rest along Arrowsmith Road. The report of the lizards in the Arrowsmith Road area was accompanied by video – there was no doubt as to the identification of those lizards – and that was a big jump from previous known occurrences.

Two other records – one along Enfer Road near Quennell Lake, and along Leask Road south of Nanaimo have yet to be verified with specimens, photographs or video.

There you go Nanaimo, the invasion has picked up pace. Keep your eyes peeled for lizards with a green tint to their scales, minute scales on their back, and generally more delicate proportions than the native Alligator Lizard.

Look at this post to help identify any lizards in your neighborhood.

If you find suspected Wall Lizards – email me at: ghanke@royalbcmuseum.bc.ca

If you find a lizard that is not a Western Skink, Northern Alligator Lizard, or European Wall Lizard – I definitely want to know about it.

Please record the date and street address (or prominent landmark) to pin down exactly where the lizard was seen. A photo would be really helpful to confirm the lizard’s identification. Happy hunting.

The Power of 1 post

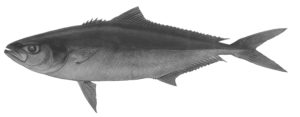

It is always satisfying to update taxonomy in the museum’s database or find and correct mistakes. This week I spent some time sorting out details on Royal BC Museum specimens of California Yellowtail (Seriola dorsalis) and Great Amberjack (Seriola lalandi). Turns out that since these fishes were collected, Seriola dorsalis has been sunk, and all our fishes are Seriola lalandi (as noted by Gillespie 1993). This carangid fish is known to move into our waters in warmer years.

While reviewing what we knew about the first BC specimen (979-11312) it became obvious that the Royal BC Museum’s database was missing some information for that fish. Fortunately, this information was easily updated – the original report was published in the Royal BC Museum’s extinct periodical Syesis (see Nagtegaal and Farlinger 1980).

Drawing of Seriola dorsalis – oops lalandi (979-11312) by K. Uldall-Ekman.

In fixing that record, I noticed that some online sources had given incorrect coordinates for this fish. Contrast the capture location of 54°35’N, 131°00’W in Caamaño Passage as reported by Nagtegaal and Farlinger (1980), with online sources which state the fish was caught at 54°35’N, 31°00’W. That missing 1 in the reported longitude determines which ocean is linked this fish.

The takeaway message? Always check the original paper rather than relying on internet sources. Precise data is everything – and in the words of a well known scoundrel: “Without precise calculations we could fly right through a star, or bounce too close to a supernova and that’d end your trip real quick, wouldn’t it.” Or in this case, you’d be landing southwest of Iceland to look for Great Amberjack.

References:

Gillespie, G.F. 1993. An Updated List of the Fishes of British Columbia, and Those of Interest in Adjacent Waters, with Numeric Code Designation.Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 1918. 116 p.

Nagtegaal, D.A. and S.P. Farlinger. 1981. First record of two fishes, Seriola dorsalis and Medialuna californiensis, from waters off British Columbia. Syesis 13:206 –207.

I’ve received a steady series of emails this year detailing European Wall Lizard locations here on Vancouver Island, and it’s now April and wall lizards certainly are active. However, an email arrived April 11th which gave me a WTH (What The Herp) moment. The email contained a beautifully focused photo of a new turtle for BC. Then it occurred to me that I’d lost count of how many turtle species have been dumped here – unwanted pets that outlived the interest of their owners.

I really like when people send me photos of things they think are unusual – and this week’s email was no exception. We know that Red-eared Sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans), Yellowbelly Sliders (Trachemys scripta2), and a Map Turtle (Graptemys sp.) have been dumped in Goodacre Lake, and Red-eared Sliders into Fountain Pond, but this new turtle photographed by Deb Thiessen (see below) certainly was not just an odd coloured slider, nor was it another map turtle. As an aside, I haven’t had a chance to catch the Map Turtle in Beacon Hill Park to get a good look at it, but I have seen it at a distance, and ID’ed it based on photos from Darren Copley and James Miskelly. It looks like a False Map Turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica). I think that’ll be a summer goal, to get good photos of that turtle to be sure which species it represents.

A Peninsula Cooter (Pseudemys peninsularis) from Fountain Lake, Beacon Hill Park, Victoria, BC. Photograph by Deb Thiessen, retired CRD Parks naturalist.

As you can see from Deb Thiessen’s photograph, this new turtle has a large shell for the size of the head, and the stripes on the neck are crisp, and bold yellow offset by black. The bold markings to me suggested Peninsula Cooter (Pseudemys peninsularis). The short claws on its forelimb indicate it is female. Males would have claws double the length of those in the photo. This animal is way outside its normal range – Peninsula Cooters are from Florida.

This animal brings our list of pet turtles to 10 species abandoned in BC ponds and lakes – that we know of. Here is the list I have of turtles that have been found in BC – way out of their native range – and (shockingly) it parallels species available in the pet trade here in BC.

Trachemys scripta (Pond Slider – both T. s. elegans and T. s. scripta)

Pseudemys peninsularis (Peninsula Cooter)

Pseudemys concinna (River Cooter)

Chrysemys picta marginata (Midland Painted Turtle, possibly also Southern Painted Turtles, C. p. dorsalis)

Graptemys pseudogeographica (False Map Turtle)

Emys orbicularis (European Pond Terrapin – always did like the word Terrapin – a bit of nostalgia from my British roots)

Chinemys reevsi (Reeve’s Turtle)

Malaclemys terrapin (Diamondback Terrapin)

Apalone spinifera (Spiny Softshell Turtle)

Chelydra serpentina (Common Snapping Turtle)

Fortunately most turtles are dumped one at a time and do not reproduce. Sadly though, I can’t say the same for the Red-eared Sliders – they now can reproduce successfully here in British Columbia (I have two pets from the first successful clutch found on the south coast of BC, ca. January 11, 2015). Red-eared Sliders now are common in artificial and natural ponds and in lakes here in southwestern British Columbia – and until recently, we were sure that each adult represented an abandoned pet (or maybe the occasional escapee). Now males are finding females. Females are finding decent nesting locations. And eggs are surviving to hatch.

Knowing that sliders can breed here, I stopped to check whether sliders and cooters can hybridize, and it has been suggested to be possible – but no solid proof. And since it is better to be safe than sorry… Does anyone know how to neuter a Cooter?

This time of year, my garden is one big mudslide. Sunny days with a blue horizon are not that common here on Vancouver Island in winter – but when they occur, we certainly enjoy them. So do our slim little European Wall Lizards.

This January and February I collected lizards which were active when the air temperatures were between 5° to 7°C. As a survivor of the Canadian prairies, collecting lizards in winter seems about as strange as an empty room in a museum collection.

I found lizards along Derby Road in my neighborhood, on Moss Rocks, at Gardenworks Nursery in the Blenkinsop Valley – winter lizard activity is nothing new here on Vancouver Island.

Lizards were found in south-facing locations with full sun exposure and when caught, were very warm to the touch. It is obvious that they are effective solar collectors and can elevate their body temperatures well above that of the chilly air – even when it is a bit windy. It is not uncommon to see lizards only exposing their head for a while, then the rest of the body. Perhaps this is a low-risk way to warm blood via blood vessels in the throat before they venture out and deal with intruding conspecifics. I haven’t seen any wall lizards feeding in winter – but that doesn’t mean they don’t. I’ll have to examine museum specimens to see what’s in the stomachs of winter-caught lizards.

An adult European Wall Lizard caught on Derby Road in Victoria, February 26th, 2018.

As of this February, the Royal BC Museum collection has 30 lots of European Wall Lizard specimens representing surface activity for each month of the year. Some people collect trading cards to get a complete set, I collect lizards to get one per month. Wall Lizards are active in winter as far north as Denman Island, and given that range, probably could extend further north of Campbell River in areas with a warm microclimate.

The collection of lizards for each season put a song from 1971 into my head – so I reworded the chorus a bit…

Winter, spring, summer or fall,

All they have to do is crawl,

And I’ll be there, yes I will,

Their spread has to end.

Introduction

I would like you to consider for a moment a poem.

One of the losses in the story of Canadian literature was the murder, at the hands of her husband, of the brilliant, Vancouver-born poet Pat Lowther. She herself is a loss—and I will take up the issue of cultural loss in a moment. But she also has a sharp eye for describing loss: for describing the long movement of history and what may so easily, if we are not careful to preserve it, disappear.

In her “Elegy for the South Valley”, Pat Lowther writes that in Canada “we have no centuries / here a few generations / do for antiquity.”

In the poem—as the rains “keep on and on” and the South Valley silts up—we see

the dam that served

a mine that serviced empire

crumbling slowly deep

deep in the bush

for its time

for this country

it’s a pyramid

it’s Tenochtitlan going back

to the bush and the rain.[1]

This is, I think, quite astonishing, for here is the recognition that the culture that surrounds us, however plain, however modest, however workmanlike, is a monument. A concrete dam in British Columbia is an Egyptian pyramid. It is the capital of Aztec Mexico. And like them, though in only “a few generations”, it too can disappear into the wilderness.

[1] Pat Lowther, “Elegy for the South Valley” in Time Capsule: New and Selected Poems (Victoria, BC: Polestar Book Publishers, 1996), pp.205–7.

Swordfishes in BC post

In an earlier post I mentioned that Luke Halpin was out surveying marine mammals and birds from the deck of the CCGS John P. Tully, and spotted something totally different west of Brooks Peninsula. The fish was estimated at 3.5-4 meters in length, and was cruising against the current just below the surface.

But until the paper announcing his find was accepted by a scientific journal, I didn’t want to spill the beans and say what he had found. His research paper (Halpin et al. 2018) will be published in the spring issue of the Northwestern Naturalist.

Photo by Luke Halpin, September 5th, 2017

This picture says it all – there is no debating what this fish is – only one species that fits the bill. Swordfish are known north to the southern Kuril Islands in the western Pacific, but Luke’s find is the northern-most record for the species in the eastern Pacific and is conclusive evidence of this species right along our coast.

A Google Earth image showing where the Swordfishes from 2017 and 1983 were found relative to Vancouver Island.

A previous record from 1983 (see Sloan 1984, and Peden and Jamieson 1988) was from just inside of our exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and barely qualified as a BC fish. The 1983 specimen was caught as by-catch at 47°36’N, 131°03’W, during an experimental fishery survey by the M/V Tomi Maru. The rostrum and tail were preserved in the Royal BC Museum’s fish collection (RBCM 983-1730-001). I am guessing the edible bits in between were cut into steaks, and ended up on someone’s dinner table. At least Luke’s Swordfish was left alone and for all we know, is happily cruising south to slightly warmer water.

References:

Halpin, L.R., M. Galbraith, and K.H. Morgan. 2018. The First Swordfish (Xiphias gladius) Recorded in Coastal British Columbia. Northwestern Naturalist, 99(1): XX-XX. (pages not set)

Peden, A.E., and G.S. Jamieson. 1988. New distributional records of marine fishes off Washington, British Columbia and Alaska. Canadian Field-Naturalist, 102(3), 491-494.

Sloan, N.A. 1984. Canadian-Japanese Experiental Fishery for Oceanic Squid off British Columbia, Summer 1983. Canadian Industry Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences No. 152: pp. 42.

We Three Kings post

Keep your eyes peeled for deep-sea fishes while strolling along our shores. In the last month, three King-of-the-Salmon (Trachipterus altivelis) have washed up in the Salish Sea. Two were found in September (21st and 26th) in the Oak Bay area, Victoria. One of these was still swimming when found. A third was found October 3rd in Hood Canal, in Puget Sound. The first Oak Bay specimen will be preserved for the Shaw Centre for the Salish Sea in Sidney, the second was not recovered, and the third will be preserved in the Burke Museum’s collection. The Royal BC museum has 18 Trachipterus specimens, with several of these from the Salish Sea area.

The King-of-the-Salmon from Hood Channel, photographed by Randi Jones.

Is this species new to the region? No. The species ranges from Alaska to Chile, and knowledge of this species pre-dates European arrival on this coast. Is this trio of King-of-the-Salmon a case of post-spawn mortality? A sign of change in our oceans? We don’t know. Actually, when you look at the diversity of marine fishes off our coast, there is a lot of basic biology that we don’t know. We also get Longnose Lancetfishes (Alepisaurus ferox) washing up from time to time, although it has been a few years since I have heard report of a Lancetfish in the Victoria region.

King-of-the-Salmon swim by passing a sine wave down their dorsal fin – they can get a fair bit of speed just by doing that. They can also reverse using the same fin flutter. They slowly turn by putting a curve in the body. However, in the first few seconds of the linked video you can see that they also swim in a more typical fishy way (using eel-like body oscillation) when they need a burst of speed or a really quick turn. If you’d like to see this form of locomotion in person – you can see it in a pet shop. Knife fishes use the same basic locomotion method – except they use their anal fin rather than the dorsal.

Close up of the head of the King-of-the-Salmon showing the premaxillary (red) and maxillary (green) bones extended, photographed by Randi Jones.

Note also in the video that the fish has a very short face compared to the Hood Channel specimen photographed onshore. As with many fishes, the jaws of the King-of-the-Salmon are protrusible – the premaxillary and maxillary bones swing out to create a tube – the gill chamber dilates, and water rushes into the mouth along with the prey. The same sort of suction pump mechanism is used by a wide variety of fishes – from tiny seahorses to giant groupers. Once the prey item is inside the fish’s mouth, the mouth closes, water is released through the gills and the prey is swallowed. The entire sequence is lightning fast – even in pipefishes and seahorses – blink and you miss it. In some fishes, the process is even audible – you can hear a snapping sound when seahorses slurp up crustaceans (and fishes). You can’t hear the same snapping sound when larger fishes engulf their prey, but it is no less dramatic an effect.

In 2014, a Louvar and a Finescale Triggerfish were found in BC – a double-header of interesting southern fishes in our waters. But wait… it looks like 2017 is also a double-header for cool coastal fish.

This summer of 2017 (and in 2016), Basking Sharks were sighted here in BC. I think every Basking Shark is newsworthy given that they were nearly eliminated here in an ill-conceived plot to protect BC fisheries (see Wallace and Gisborne 2006 for that sad story). This year’s Basking Sharks were found in Caamano Sound in July, and near the Delwood Seamounts in August. Was it one roving shark? Or two? Are there others?

This September however, Luke Halpin was out surveying marine birds from the deck of the CCGS John P. Tully, and spotted something totally different west of Brooks Peninsula. The fish is estimated at 3.5-4 meters in length, and was cruising against the current just below the surface.

We are really fortunate that it was sunny and seas were so calm – because his picture leaves no doubt as to the fish’s identification. The best part about the story is that the fish is still out there. Don’t get me wrong, I’d have loved to have the fish as a specimen for the museum’s collection – but then again, it would require a custom vat – three to four meter fishes don’t fit in jars.

This species is known north to the southern Kuril Islands in the western Pacific, but Luke’s find is the northern-most record for the species in the eastern Pacific and is conclusive evidence of this species as a new addition to our coastal fish fauna. Which species did he find? You’ll have to wait until he publishes his observations in a scientific research paper. Consider this a trailer – a teaser – there’s a big fish out there – it is cool… and I am jealous. I would love to see this fish alive.

100 Meter Dash post

The Doncaster population of the European Wall Lizard probably is 6 years old based on conversations I have had with home owners. In the Google Earth image – the white dots are known locations – the green dots are new locations for 2017.

How do I know these are new? Homeowners specifically said they had no lizards in 2016 – but they certainly do now. That’s the power of local knowledge and citizen science. The green dots along Oak Crest Drive were newly reported in the spring of 2017, with at least three adult lizards now known on the property. The two green dots along Cedar Avenue to the northeast are based on sightings of at least three young lizards – probably lizards that hatched this year and got well-clear of their parent’s territory. Cannibalism is a good emigration motivation.

Based on where lizards were known in 2016, these 2017 records represent range extensions from 20 to 100 meters. Compared to their body size, that’s pretty decent dispersal given that adult lizards only grow to 21 cm (those fortunate enough to have a perfect tail), and in many cases, the dispersing lizards are young-of-the-year at 8 or so centimeters in total length.

If younglings continue to bolt at this rate and make a bee-line south, I will have lizards in my garden in 2 years. More realistically, it will be another 3 years before we see them along our raised beds or in our greenhouse – not that I’m counting.

We now have 21 orca specimens at the Royal BC Museum—the latest to arrive was T-171, a 6.07 meter female Biggs Orca which was found near Prince Rupert, October 19th, 2013. She had pinniped skulls, vibrissae (whiskers) and partially digested bones in her gut but was emaciated. Why was she emaciated?

During the necropsy, researchers discovered that T-171 had mid-cervical to lumbar vertebrae with severe overgrowth of the neural arches and lateral processes (noted as spondylosis in the necropsy) – the overgrowth looks roughly like popcorn or cauliflower – and had the effect of interlocking some vertebrae. This likely explains her emaciated state. Was she able to hunt? Was she supported by her relatives?

The skull of T-171 (ventral (palatal) view [left], right side [center], and dorsal view [right]) awaiting its catalog number and final place in the Royal BC Museum collection.

Comparison of T-171’s vertebra (left) with overgrowth of bone vs. the normal vertebra of another Biggs Orca (12844) (right). The two vertebrae are not from the exact same position along the spine, but the difference between the two is still shocking.

Many of T-171’s vertebral centra are eroded and porous – not like those of a healthy animal (12844).

The overgrowth of the neural arches pinched the spinal chord of T-171; compare to a neural arch of 12844 (right). The vertebral malformation must have limited this animal’s mobility. It is hard not to anthropomorphize and imagine the discomfort due to this deformation.

T-171 originally was prepared for exhibit at the Royal Ontario Museum, but they wanted a clean articulated skeleton for exhibit. In contrast, we were interested in T-171 because of its skeletal malformation. To make a short story long, we came to an agreement with the ROM to transfer T-171 to the Royal BC Museum, and since, the ROM has acquired L95 (Nigel), a 20 year old southern resident who was found near Esperanza Inlet, March 30th, 2016.

Which Orca is next? In most cases we have no clue – it is not like we hunt orca just to add them to the collection. And we don’t usually have a production line of specimens in preparation. New specimens are acquired when a body washes up, and we make a snap-decision to cover the cost of specimen recovery and preparation. However, September 15, 2016, T-12A (Nitinat) was found off Cape Beale and towed to Banfield. I was contacted September 16th to see if the Royal BC Museum was interested (obviously that was a YES), and now his massive skull is being prepared. Once degreased, Nitinat’s skull will be added to the Royal BC Museum collection – sometime in 2018 – and made available for scientific research.

As a kid I collected many things – from reptiles and amphibians to model airplanes to Star Wars cards – and now look where I am. I dress in black and white as a Stormtrooper with the 501st legion and collect black and white delphinids – Killer Whales – for the Royal BC Museum. Life sure takes you to unexpected destinations.

A little while back I was musing over a spot on my Wall Lizard map that shows a large expanse east of Highway 17 between Cordova Bay Road to Mt Newton Cross Road that appears to be Wall-Lizard-free turf. Wall Lizards are crawling everywhere just the other side of the highway on Tanner Ridge. Either no one has reported lizards from this area – and it seems unlikely given how many reports I receive each year, or lizards have not been able to cross HWY 17.

Cedar Hill Road in the Southeast Cedar Hill area also seems to be a decent barrier even though it is not a particularly busy road. Lizards have been in that area for about 6 years(as of 2016) and have crossed Derby Road without a problem – but not Cedar Hill Road. Cedar Hill may be just busy enough to limit the survival of adventurous lizards.

It seems interesting that a lizard as fast as the Wall Lizard could not cross – but then again – why would they? Young ones disperse to avoid cannibalism, but perhaps the noise, vibration and sight of passing vehicles is enough to dissuade all but the most suicidal of lizards.

I recently tripped across an article detailing road crossing behaviour in snakes (Andrews and Gibbons 2005). In their study, smaller snakes seemed to avoid crossing roads, whereas larger snakes have no problem with the concept. I wonder if the same is true for Wall Lizards? Interestingly, all snake species they studied crossed perpendicular to the road’s length – an adaptive behaviour minimizing distance and time on the tarmac. Some species froze in place when a car passed – that is maladaptive – and significantly increased an animal’s exposure to vulcanized rubber.

I have not seen Wall Lizards crossing a street – but would be interesting to see if they too cross perpendicular to the curb, and whether they blast across or dart and pause – unintentionally increasing their risk of catastrophic z-axis reduction.

Andrews, K.M., and Gibbons, J.W. 2005. How to Highways Influence Snake Movement? Behavioural Responses to Roads and Vehicles. Copeia 2005(4): 772-782.

Another lizard arrived in BC last week. We can add Brown Anole (Anolis sagrei) to our list of accidental imports – but this certainly is not the first one to have arrived by accident in BC. Many lizards travel the globe as stow-aways. This one travelled here in its egg along with a Snake Plant (also known as the Mother-in-Law’s Tongue). Sansevieria are popular houseplants – Snake Plants are easy to keep and look neat. My wife bought one for our living room – no lizards in our plant though.

Where was the plant from? Who knows. This plant could have come from anywhere. Brown Anole’s have invaded Florida, and southern parts of Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. They also have invaded Hawai’i, southern Texas and southern California along with their relative the Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis). The Green Anole is native to the south-eastern United States, and in their native range, Green Anoles may be forced out of their usual habitat by their exotic relatives. Brown Anoles are native to Cuba and the Bahamas.

Even if it got loose, this anole would not survive our winter. It was no real threat to our environment or fauna, but does show that the transport of exotic species is ridiculously easy – an egg in the soil in a plant pot. This time we are fortunate. Only one egg was present. Anoles are light-weight arboreal lizards which lay one egg at a time, and they are not parthenogenetic. Anole eggs develop in alternate ovaries at about a two week interval – if I remember correctly. This ensures the female lizard is not excessively encumbered, and for us it meant that only one egg likely was present in the pot (or any other pot at the home hardware store).

Brown Anole eggs are a bit bigger than a Tic-Tac candy, so no wonder they are overlooked – they also are buried a centimeter or so in the soil – so they’d be out of sight. As long as the soil was not disturbed, was warm and moist – but not too wet, and the egg was not rolled, the developing embryo would survive transport.

I wonder where this lizard’s brothers and sisters ended up? They could be anywhere. Since the lizard travelled here in an egg, I vote we name it Mork. Na-Nu Na-Nu.

Just tripped across this fish while sorting out odd records in the RBCM fish database.

999-00114-001 – unidentified fish – Family Triglidae (Searobins, Gurnards)

Well, it turns out to be Prionotus stephanophrys – a Lumptail Searobin – and a new family, genus and species for BC. Three other triglid species (two of them are Prionotus species) are known to stray into Atlantic Canada.

This one was caught in 1998 on La Perouse Bank, it was added to the RBCM collection in 1999, and sat there ever since. No one had taken a second look at this specimen – until today. It was completely new to our system and as such, I had to add the genus and species to our database’s taxonomic tree.

Until now, its northern record was off the mouth of the Columbia River – this new(ly rediscovered) record extends this family north about 260 km in the eastern North Pacific Ocean.

The lower three pectoral rays of this fish are almost like fingers – it probably walks along the bottom like other triglids – the walking mechanism makes me think of face-hugger Alien larvae.

I took these photos of Royal BC Museum lizard specimens with my iPhone 4 through the eyepiece of the old dissecting microscope in my lab. Then sent the photos via two emails to office thanks to WiFi – and to think – this is the “low-tech” way of doing things these days. Low-tech – sending files through the air from a hand held device… I have to laugh how technology has changed since I was a kid with my first pet lizards. The nerd in me can’t help but hear James Earl Jones’ voice – “Several transmissions were beamed to your inbox. I want to know what happened to the scans they sent you.”

In earlier blogs I have mentioned scale differences between BC lizards – so I thought I may as well take close-up shots to clearly show the differences. Under a dissecting microscope (diss-secting, not die-secting), you can easily see the shape of the bead-like back scales of the European Wall Lizard (Podarcis muralis). It’s like a microscopic cobblestone pavement. Each scale is about the diameter of a standard sewing pin.

European Wall Lizard (2112)

The larger back scales of the Northern Alligator Lizard (Elgaria coerulescens) are painfully obvious, and each scale has its own raised keel. The keel gives each scale an angular appearance.

Northern Alligator Lizard (1358)

The Pygmy Short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma douglasii) has a really complex squamation with tiny granular scales interspersed between clusters of larger keeled scales. The larger scales are raised into spires above the general scale-scape (the lizard equivalent of landscape).

Pygmy Short-horned Lizard (323)

Western Skinks (Plestiodon skiltonianus) by contrast are painfully even and smooth – yawn. It’s a good thing they have speed-stripes and a bright blue tail to make them stand out in a crowd.

Western Skink (1964)

Western Fence Lizards (Sceloporus occidentalis) have scales each with a trailing spine – characteristic of all Sceloporus species. Some, like the Crevice Spiny Lizard in the United States have really robust spines on their scales, others like the Sagebrush Lizard have tiny spines. Cordylids in Africa take spiny scales to a whole new level.

Western Fence Lizard (705)

Sorry, I forgot a scale bar in the photos, but the images were fairly close to the same magnification.

You’d think that sharks and rays would be pretty well known along our coast. Did you know that two Hammerhead Sharks have been found off Vancouver Island? Even a Tiger Shark has strayed north to Alaska. Did it swim along the BC coast, or did it take a more direct route from Hawai’i? We’ll never know. However, in 2016 a new shark was added to our fish fauna – the Pacific Angel Shark (Squatina californica) – based on a clear photograph by Mark Cantwell and his detailed description of the dive location.

We have known since 1931 that Angel Sharks ranged north to Seattle, and there is a single record from Alaska. The specimen label for this 35 cm Alaskan female had been lost (Evermann and Goldsborough 1907) and we cannot pin down its collection location with certainty. Until now, we had no Angel Shark records for British Columbia – but it was only a matter of time.

On the 30th of April, 2016, a single adult Angel Shark was sighted by a diver off Clover Point right here in Victoria. The shark’s gender cannot be determined from the photograph since claspers, if present, are not visible. The Angel Shark was found in about 12 meters of water, about 30 meters off the point. The diver estimated the shark’s length at about 1.1 to 1.2 meters in length. The specimen was not collected, but it would have made a fantastic museum specimen.

King and Surry (2016) published the discovery of this shark in BC in a recent issue of the Canadian Field-Naturalist. While this now is not breaking news – in fact it is a year late – people may still want the primary reference to our latest elasmobranch.

PDFs are available here [as a new paper, King and Surry (2016) is available by subscription to The Canadian Field-Naturalist or by contacting the primary author]:

Belted Kingfishers (Megaceryle alcyon) usually take fishes – why else would they be called kingfishers. They sometimes take crustaceans and frogs, and I’d be shocked if they turn their beaks up at big juicy insects. However, mammal predation is quite a dietary shift. Apparently no one explained the meaning of “fisher” to a kingfisher in the southwestern Yukon.

This female obviously read its species description. Looks like she caught a young goldfish. (From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belted_kingfisher#/media/File:Belted_Kingfisher_with_prey.jpg)

A paper came out in a recent issue of the Canadian Field-Naturalist (see Jung 2016) detailing the capture of a Western Water Shrew (Sorex navigator) by a Belted Kingfisher. That would make a decent meal and a real energetic boost for the Kingfisher. Jung (2016) mentioned that Belted Kingfishers have been known to take Eastern Water Shrews (Sorex albibarbis), and he (Jung 2013) also reported on a kingfisher trying to subdue a Spotted Bat (Euderma maculatum).

From: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8f/Belted_Kingfisher.jpg

Imagine if kingfishers changed tactics to regularly prey on other small animals? Their ecology could converge on that of butcher birds (shrikes). What’s next? Lizards and snakes?(Yes, shrikes impale their prey on thorns (or barbed wire) to age a bit).

Sure glad kingfishers aren’t the size of a Banshee or Leonopteryx from Avatar, or we’d all be at risk when swimming.

Keep your eyes on the sky. And as for that specific Water Shrew, all you can say is: “Hair today, gone tomorrow.”

PDFs are available here:

Was this an odd title? Actually I think the song went,

“On top of spaghetti… all covered with cheese,

I lost my poor meat ball… When somebody sneezed.

It rolled off the table… and onto the floor.

And then my poor meat ball… rolled out of the door.

Wow that was a dredged from deep cephalic crevices…

Anyway, I got a tip from Purnima Govindarajulu, my herpetological counterpart in the Ministry of Environment that she’d seen a European Wall Lizard on Mount Tolmie here in southern Saanich. Given how fast and far Wall Lizards are spreading, it was only a matter of time before they colonized this rock. This pocket of lizards will form another expanding sub-population – pretty-much midway between the single lizard I saw at the University of Victoria and the lizards near Doncaster School.

This morning (April 27th) was nice and sunny, and I hiked up to the summit after dropping my daughter at daycare. What did I find first? A Northern Alligator Lizard. That made me very happy – I don’t see those everyday and this lizard was more than patient with the iphone-wielding twit who wanted its picture.

Then less than 2 meters away were the Wall Lizards – five of them. A meter or so along the road, another Wall Lizard. Up along the southeast corner of the reservoir – another large male Wall Lizard.

Yep, looks like they have found a solid toe-hold in this region. Cedar Hill X Road may make a decent barrier to northward dispersal (not that Wall Lizards aren’t north of there anyway) – but they will easily spread southeast and southwest into gardens adjacent to the park. Note the small scales and green colour on this Wall Lizard’s back, compared with the larger coppery scales on the Alligator Lizard (above).

Keep your eyes on rock gardens, rock walls, woody debris, and any bedrock with decent cracks for shelter. The photo below shows just how slender the Wall Lizards are – this one with an intact tail is the largest lizard I have caught to date (21.2 cm total length). After checking the RBCM’s herps database, I see that the only months where I haven’t caught Wall Lizards are January and February – too bad that this spring was consistently cold and wet. I have missed my chance to get a full year’s worth of lizards in 2017.

Somnolent Sculpins post

Yesterday I worked with Chris O’Connor from our Learning Department – we took some children on a tidepool tour. The main point was to chat about museum collections and things we record or measure when we are out sampling. We didn’t go crazy catching fishes, only taking 3 Tidepool Sculpins (Oligocottus maculosus) in the end. But we talked about our role as museum researchers, and why we take more than 1 specimen (if possible) to get an account of variation within and between species.

You can see slight differences between these fishes – even an injury – just like the subtle, or not so subtle differences we see in each other.

The three fishes will be added to the Royal BC Museum’s ichthyology collection, but before that, they are fixed in 10% Formaldehyde. Researchers used to drop fishes directly into Formaldehyde – many fishes died horrible deaths. When I accidentally get Formaldehyde in a cut – it stings intensely – I couldn’t imagine being dunked directly into that chemical.

Today we are more humane, and give fishes an overdose of anaesthetic before immersion in Formaldehyde. They are dead before they are fixed, and are preserved with a relaxed posture. The primary anaesthetic I use is 2-Phenoxy-Ethanol, but it is hard to get without ordering from a chemical supply company, and the chemical is a suspected carcinogen. I still have about 500 ml of the stuff – so I will use up what I have. Do I really want to buy more? Maybe not.

Do we have safer options? Yes, Clove Oil is a good anaesthetic if mixed as an emulsion in a small volume of 99% Ethanol. But you have to carry a jug of 99% Ethanol everywhere you go – that may not go over well at a Police check-stop. The up-side to this chemical mix is that you smell spicy at the end of the day if you accidentally spill some on yourself.

People have tried Alka-Seltzer tablets. They fizz and release CO2, which knocks-out fishes – but the process is slow and some fishes (those like catfish that gulp air to survive in low oxygen conditions) are resistant and survive way too long in a stressful condition.

A few months ago I tried using Oragel (20% Benzocaine) on European Wall Lizards – colleagues had found it worked well on amphibians. They put Oragel along the spine of an amphibian and it soaks into the skin; I give lizards an oral dose. It renders bullfrogs and wall lizards unresponsive in 20 seconds to a minute. Oragel seems to be a convenient anaesthetic for these invasive herpetiles.

Yesterday, I told the tidepool group that we’d be performing an experiment – I tried Oragel for the first time on the 3 sculpins we caught. As I hoped – less than 20 seconds and the fishes were out cold. 2-Phenoxy-Ethanol takes about the same time on similar sized fishes.

The beauty of Oragel is that it is readily available, and if you run out, you can stop by the nearest pharmacy. It also is safe – we use it on sore teeth or gums. Perfect – it works fast on specimens and is safe for the researcher.

Perhaps someone needs to do a larger scientific study to see how effective over-the-counter Oragel is on larger fishes. Maybe this is an effective over-the-counter tool for preserving new museum specimens.

A Big Shark in BC post

A specimen with no data is not worth keeping. A specimen with vague data is not worth keeping either. The Royal BC Museum’s ichthyology collection contains a vertebral centrum with cartilaginous remnants of its respective haemal arch and neural arch from a shark that washed up November 5th, 1975 (only a few months after Jaws was released in cinemas). It was cataloged as 976-00052-001 in the fish collection (with a variant of the catalog number listed as a previous number ~ B.C.P.M. #97652). Our electronic database only had a collection date for this centrum (no location, no collector).

Flip to our original paper catalog, and we find that there is indeed a collection location: Ahousaht Village, Flores Island – but this never got translated to our electronic database. The paper catalog states that the shark washed up on a beach – but there was no latitude and longitude provided for the record beyond 49°N, 125°W. If you plot the western-most limit of 125°W, it is nowhere near Flores Island – so the location is questionable. Ahousaht Village’s nearest beach is at about 49°16’N, 126°03’W.

Worse yet, the vertebral centrum indicates that this was a big shark – we don’t have a lot of big sharks here…

Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) reaches 6 meters

Pacific Sleeper Shark (Somniosus pacificus) reaches 5-6 meters

Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus) reaches at least 9 meters

The shark centrum in the Royal BC Museum collection is about 7.3 cm in diameter – it spans most of the palm of my hand. This must have come from a decent-sized shark. Was it a small Basking Shark? A large Great White? A large Sleeper Shark? It’s not ‘reptilian’ so we can rule out Cadborosaurus (whew). Hang on, Cadborosaurus’ so-called “type specimen” was a photograph of a digested basking shark – Hmmm…

It is a shame no one bothered to take a skin sample – the scales may have been diagnostic. What about teeth? A sample of teeth – even one tooth – would have been enough to identify this fish. Sadly though, nothing remains other than this centrum and a bit of cartilage. It was fixed in formaldehyde and stored in isopropanol – so I think we can forget sending a chunk to Guelph for DNA barcoding. DNA barcoding wasn’t a thing back in 1975, so tissue samples were not preserved for future analysis.

If no one in Ahousaht has a photo of this shark on the beach, or some teeth stashed away, all I have to say is , “Sorry Charlie, the Royal BC Museum wants specimens with good data.”

A Winter so Harsh post

This winter has been cold here in Victoria – relatively speaking. We have had lots of rain, several rounds of snow – and I even had to shovel my driveway and sidewalk. Actually I have had to shovel several times this winter. The rest of the country is not all that sympathetic to the wintery-woes of its Pacific Islanders.

One odd feature of Victoria is that Anna’s Hummingbirds are present year-round – because people feed them. Without artificial feeding stations, they likely would migrate south in autumn with the Rufus Hummingbird and return each spring. It still strikes me as strange to see a hummingbird in winter – given that I moved here from Winnipeg.

In my neighbour’s yard there is Holly bush that is a regular nesting site for our resident male Anna’s Hummingbird – the spot must be coveted because the prickly leaves are a great deterrent to would-be nest thieves.

This nest from 2005 was near the junction of Government Street and Niagra Street in James Bay – also in a Holly bush.

Our hummingbird – yes we are possessive even though we don’t feed hummingbirds in winter – is a regular visitor to our veggie garden and flowers in summer. It stayed this winter even though it was snowy and cold. Someone nearby must have a hummingbird feeder.

Not all Anna’s Hummingbirds were so lucky this year. Today I received a nest containing two feathered nestlings which were snuggled together in their soft little lichen-cup nest. This is certainly an early nesting attempt – they are known to nest from February to August, but nesting this early in the spring is a big risk.

The fate of the female is a mystery (males don’t raise their young). Did she hit a window? Run short of food and die? Did a free-range domestic cat get her? These two nestlings were in a sheltered spot alongside a house here in Victoria, but without a parent, they didn’t last long. Natural selection can be as cold as this winter.

In 2006 I spent a month at sea on the CCGS W.E. Ricker, collecting hundreds of deep sea fishes during a Tanner Crab Survey. Most fishes were identified the traditional way using anatomical features, but we didn’t have an extensive library on board, so many ‘field’ identifications were wrong. Such is life on the high seas when you are rushed to process samples.

Several snailfishes and of course the poorly known Flabby Whalefishes were only identified to genus. One snailfish with its distinctive pelvic girdle resembling a pair of bat’s wings – was simply labeled as “Batwing.” It was a few years later while sorting out some of the samples, that I tripped across a paper by David Stein (1978) describing our “Batwing” species in detail – Osteodiscus cascadiae. Keep in mind that the last comprehensive book on BC fishes – Pacific Fishes of Canada – was published in 1973… I was 6 years old. Pacific Fishes of Canada needs an update – it is woefully out of date.

This week I have been cataloging the last of the fishes caught on the 2006 Tanner Crab Survey – Screech – I know what you are thinking. A decade has passed since these fishes were caught. I am not a slacker – well, some would argue that – but there are many reasons why I am only now sorting and cataloging the last of the Tanner Crab specimens. Forgive me if progress is slow.

Many of the specimens we collected in 2006 had a small plug of tissue removed for DNA Barcoding. Three specimens (DNA barcode field tags from left to right, G5036, INV792, and 0738-Bo2), from Queen Charlotte Sound and west of the northern end of Vancouver Island were identified as Careproctus canus. If this is correct, they are the first for British Columbia.

The same can be said for specimens (barcode field tags from left to right, R5826 and G5026), both from Queen Charlotte Sound which were identified as Careproctus attenuatus. If correct, they are the first of their kind for BC, and both species C. canus and C. attenuatus, are way-south of their known ranges in the Aleutian Islands. We also caught one other snailfish identified as Paraliparis melanorhabdus (15943) – if correct it is the first specimen for the RBCM, but not the first for BC.

When I got down to the last few unidentified fishes to catalog in the RBCM database, I found that they had tags from the DNA Barcoding project. Obviously I looked up the molecular identification, but I have to wonder whether a genetic sequence was used to identify these new snailfishes, or whether the DNA barcoding team used our field identifications. We certainly do not carry an exhaustive library at sea, and we do our best to identify fishes with what we have at our finger-tips while the decks are heaving and rolling. Since I don’t trust my own eye regarding snailfishes – these noteworthy records need to be verified – and I think I’ll send them to a snailfish expert that I know just south of the border.

However, two specimens of Gyrinomimus (lovingly known as Flabby Whalefish) were identified as G. grahami (barcode tags, left to right INV0718 and R5828), and both were from west of the northern end of Vancouver Island. They don’t look much better in person. We left these specimens identified to genus because we had no literature for Flabby Whalefishes on board. As a result, I know the species-level identification did not come from me – and had to be based on molecular information. YAY, Gyrinomimus grahami (15942, 15935) is new to BC.

These interesting records alone justify the time taken to collect and send DNA samples to Guelph for the barcoding project. I may not be a gene-jockey, but if the identifications of these fishes are correct, we will rack up another three new species for BC, boost our knowledge of biodiversity, finally have two of our whalefish specimens o-fish-ally identified. Now to compare the newly identified whalefish specimens to the other 10 jar-loads of specimens to see if we have one or more species in our collection.

Thanks all you DNA barcoders – particularly Dirk Steinke who was out with us in 2006 – couldn’t have done this without you.