Human History Curators

Small Spindle Whorls in the Ethnology Collection of the Royal BC Museum

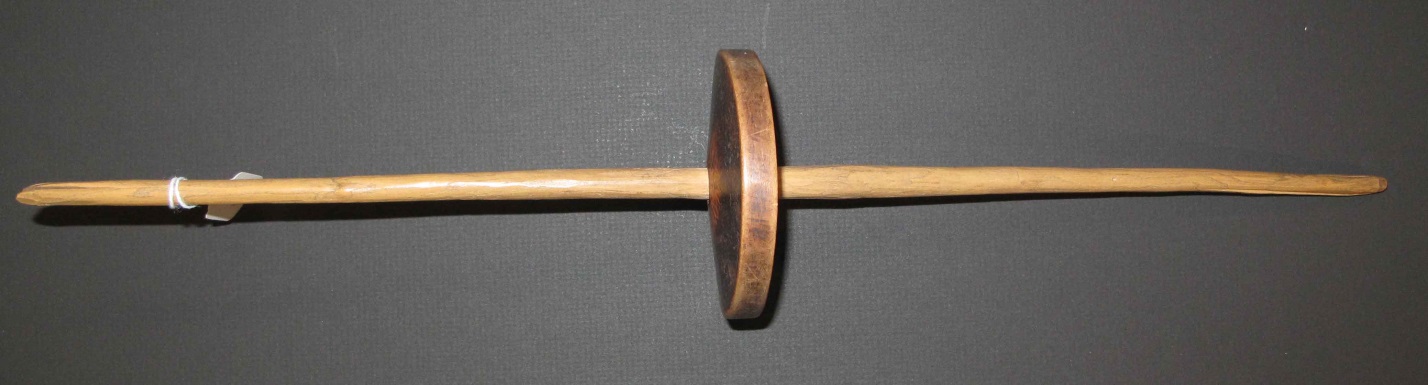

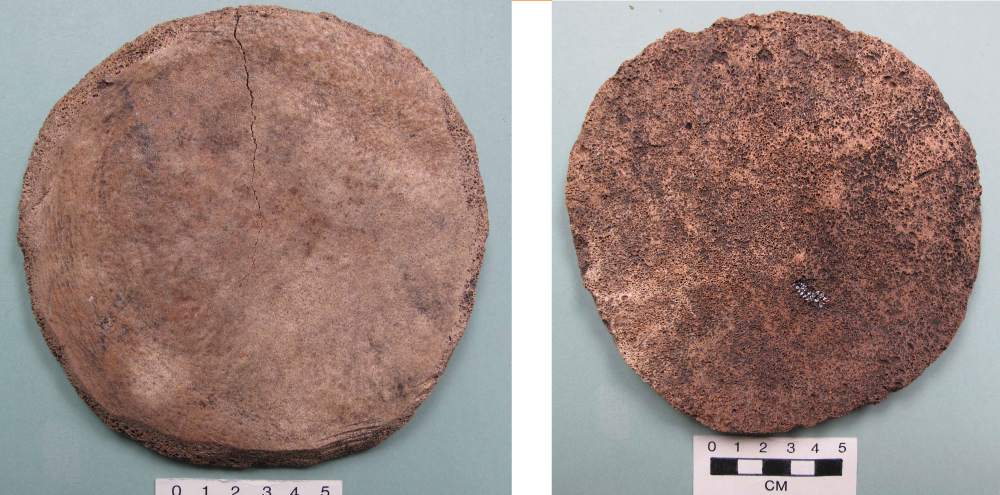

Figure 1. Small Spindle Whorls in the Ethnology Collection.

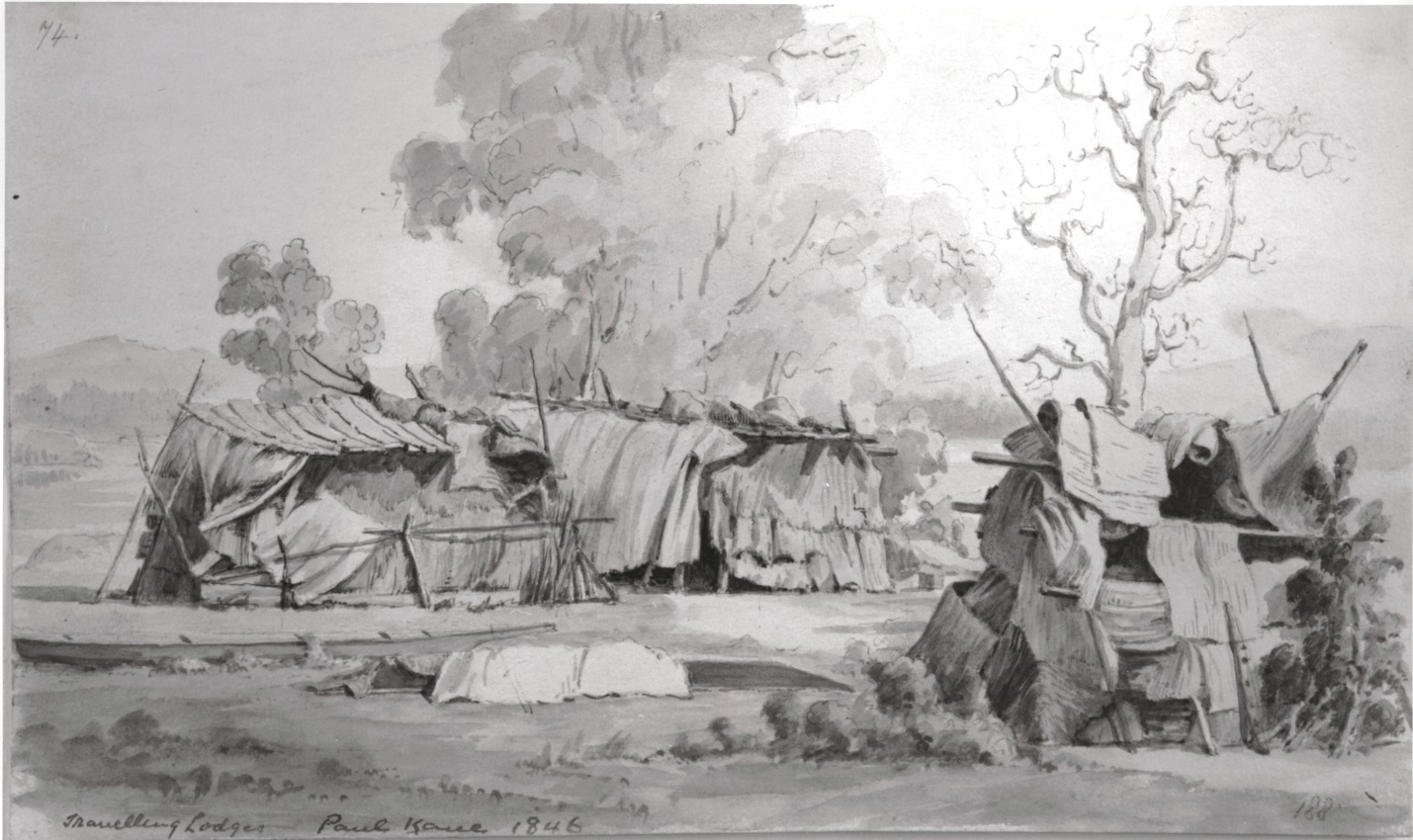

Much of the attention in the literature has focused on the large spindle whorls used by speakers of languages in the Salish linguistic family on the south-eastern coast of British Columbia. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, small spindle whorls were found among peoples belonging to several of the larger linguistic families. The lack of iconography on most of these smaller spindles likely contributed to their being of less concern to researchers than the study of the larger whorls – many of which have geometric, anthropomorphic or zoomorphic design patterns.

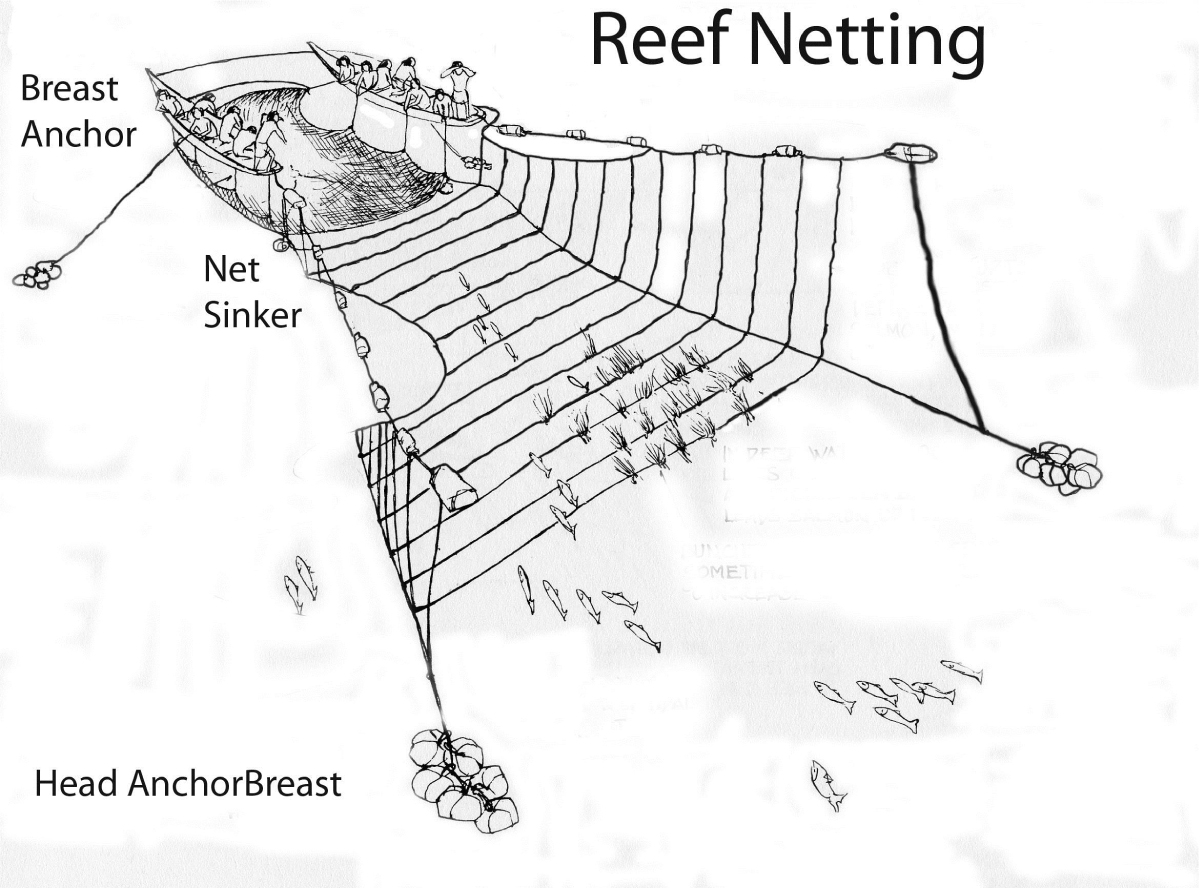

The resurgence of indigenous weaving with the use of large spindle whorls in recent times has focused primarily on the use of animal wool. It earlier times the small whorls were primarily used for producing finer and longer threat made from stinging nettle. Stinging nettle thread would have been mass produced for the making of fish and bird nets as well as for a general tying string. Given that small whorls were introduced before the larger whorls, suggests that the earliest introduction of whorls into this region of North America was primarily related to the procurement of fish and birds. Although other plant fibres, such as fireweed, were likely used in earlier times, the use of animal hair and sinew along with plant fibres and bird down for clothing was probably a feature that developed later in time among some populations.

Morphology and Function

Most spindle whorls fall into two distinct sizes with a limited size range that we can refer to simply as large and small. The 20 smaller whorls in the RBCM ethnology collection range in diameter from 48mm–94.4mm. However, the upper range is biased by the three wooden whorls that range from 67-94mm. The diameter of the 17 sea mammal bone whorls ranged from 48mm-79mm. Wooden whorls are lighter than bone whorls and need to be larger to be of equivalent weight. The size of the hole in the whorl is related to the size of the whorl. Although the diameter of the central hole of the whorls ranges from 8mm-13mm, the smaller 48-65mm whorls have holes with a smaller range of 8-9mm.

The weight of the whorls in the RBCM collection can only be measured on ten whorls that are removed from their spindles or do not have associated spindles. The weight range of the 10 whorls is 16.6 – 45.9 grams. Where whorls were attached to the spindle, weights were taken of the combined elements of whorl and spindle. The range of the latter was 43.9-64 grams. The length and weights of the spindles used with small whorls was much less than those used with the larger whorls.

Regional samples are not large enough for any definitive comparisons, but comparing the more common sea mammal bone whorls, the three from the northern coastal regions are the larger in diameter range from 69.5-89mm. The five Heiltsuk examples range from 59-77mm, the three Nuxalk examples from 49-68mm, and the Kwakwala speakers six examples have a range of 48-69mm.

As a comparison, the seven bone whorls from Kwakwala speakers in the American Museum of Natural History have a similar diameter range as those in the RBCM of 40mm–80mm in diameter. Of the eight examples of Nuxalk small whorls in the Canadian Museum of History, three bone ones range from 50-64mm and five cedar ones range from 71-90mm. The five cedar Gitksan examples range from 59-95mm and two Tsimshian ones from 62-67mm. The one bone Nisga’a example conforms to the smaller size at 53mm. Two “central coast Salish” bone whorls in the Burke Museum range from 63-72mm, with a single stone Cowichan example being 50mm.

Sometimes the ethnographic literature is unclear about whether the smaller or large whorls are being referred to. Museum records may also have incorrect information added long after the whorls were collected – confusing the uses of small and larger whorls. Some small whorls were occasionally placed in ethnographic collections when, in fact, they were found in shell middens. In museum settings one needs to be aware that wool may have been added to museum spindle whorls for display purposes that were not part of the original purchase.

The size of spindle whorls differs according to the size and weight of the required thread. Most spindle whorls cluster into a standard small size and another grouping of larger varieties. The use of a small spindle whorl imparts a higher degree of twist and produces a finer and stronger thread than can be made with the larger spindle. It is for the latter reason that small whorls were primarily use for producing the finer threat made from stinging nettle. Stinging nettle thread was mass produced for the making of fish and bird nets.

The important considerations in the functioning of a spindle whorl are its weight or mass and its radius. The shape of the whorl and how its mass is distributed is also important. A spindle whorl with a lenticular cross section is thinner at the edges and will therefore have less inertia in its spin. A whorl must move at a constant speed in order to produce the best uniformity in the material being spun. The radius of the whorl and size of the spindle shaft will determine the size and weight of the fibre ball that accumulates on the whorl. For a technical functional analysis of spindle whorls see Barber (1991) and Loughran-Delahunt (1996).

In using the small spindle whorl, the yarn was fastened to the longer end of the spindle. A person sitting on the ground drew out the yarn with one hand as it was twisted and with their other hand rolled the spindle shaft below the whorl rapidly down the thigh or shin.

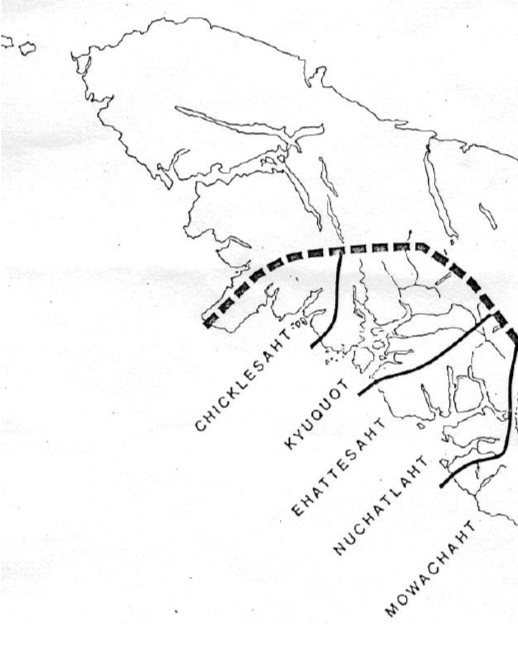

Ethnographic collections of small spindle whorls are found among the Nisga’a, Haida, Haisla, Heiltsuk (Bella Bella), some Tsimshian speakers, Nuxalk (Bella Coola), Kwakwala speaking peoples and Nuu-chan-nulth peoples. There are no examples of small whorls in the RBCM ethnology collection from First Nations

that belong to the Coast Salish linguistic family. Larger spindles from the latter region will be dealt with in Part 3 of this series. The RBCM collection does have archaeological examples of small spindle whorls from the latter area (see Part 1).

Practices & Materials Used

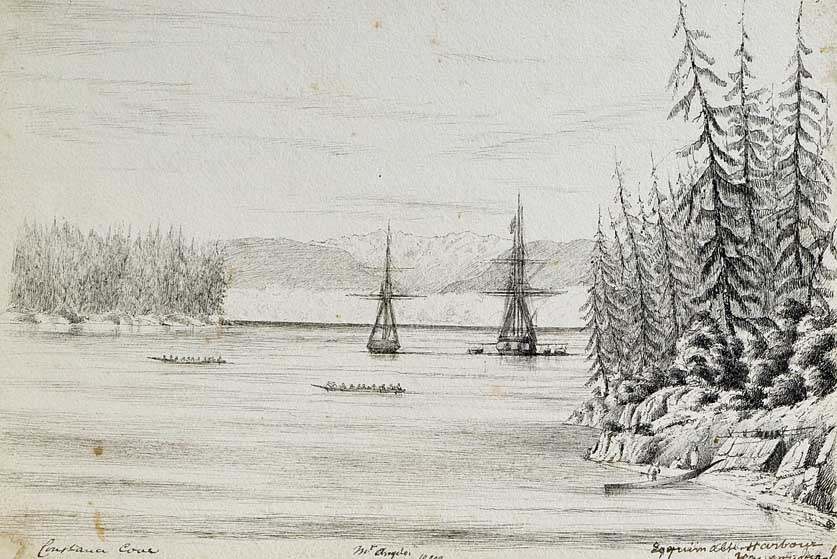

The ethnologist Franz Boas documented information on spinning and spindle whorls in the 1886 to 1897 period. He focused his attention on the Kwakwala speaking peoples of North-Eastern Vancouver Island and the Nuu-chan-nulth peoples of the West Coast of Vancouver Island, who he saw as being less affected by European culture at the time.

Boas’s First Nation consultants described four different sizes of spun thread that were used for different purposes. The method of free-dangling of the whorl was not practiced in British Columbia in the historic period.

Small spindle whorls are mostly made of sea mammal bone. Boas describes most spindle whorls from the west coast of Vancouver Island as being made of whale bone, with a few of wood and stone. Small spindle whorls in the Berlin Museum from the west coast of Vancouver Island have geometric and realistic designs. Among the “Kwakuitl”, Boas did not observe any with designs (Boas 1909:373-374).

Boas (1909:372-373), describes in detail the making of twisted stinging nettle string which is coiled up in a basket and then spun. His figure 67 shows a 34cm long, quarter section maple wood spindle shank with a small whorl attached near the thicker middle. He notes:

“The spindle-whorl is made of bone of whale, the anterior part of the skull-bone being preferred. It is ground down on a gritstone. Then it is polished, and finally rubbed with deer-tallow. The size of the spindle-whorl differs somewhat, according to the size of the thread to be made. The sizes of those in the Museum [Berlin] collection range from 7cm to 8cm. in diameter. They are not decorated. Many of the spindle-whorls from the west coast of Vancouver Island (Fig. 68) are decorated with geometrical and realistic designs. Most of these are also made of bone of whale, while a few are made of wood and of stone.”

Boas notes that his figure 68a “corresponds in style to other decorated tools of the Nootka”. He states that: “it is remarkable that the spindle-whorls from this whole region are all small, while spindles used by the tribes of the Fraser River region are very large”.

Carved figures of humans and animals are rare on small spindle whorls. Boas’s figure 68, is reproduced here as Figure 2. His figure 68a shows a squatting human with the central hole for the spindle through the centre of the figures chest. The figure is cut out within a solid ring forming the outer portion of the whorl. This figure is reminiscent of some of the later larger whorls from south-eastern Vancouver Island with human figures around a central hole. Three of the top row images and one of the bottom images show the designs that Boas refers to, while the plain ones on the bottom row are typical of the Kwakwala speakers of North-eastern Vancouver Island. These same whorls are incorrectly referred to as being from the “Lower Fraser River” in a later Boas publication (1955:371; fig. 296, p.283).

Figure 2. Small Spindle whorls from the west coast of Vancouver Island collected by Franz Boas for the Berlin Museum in the late 19th century (After Boas 1909, fig.68).

Washington State. Uses of the Spindle Whorl.

In reference to the southern coast, James Swan notes that the women “spin the thread and twine for making nets. This operation is performed in a very simple and primitive manner by twisting the strands between the palm of the hand and the bare leg …these cords, when spun, are tied up in hanks of thirty or forty fathoms each, and carefully stowed away for future use. The men make the nets” (Swan 1969:163-164).

The nets “are made of a twine spun by themselves from the fibres of spruce roots prepared for the purpose, or from a species of grass brought from the north by the Indians. It is very strong, and answers the purpose admirably. …The nets vary in size from a hundred feet long to a hundred fathoms, or six hundred feet, and from seven to sixteen feet deep” (Swan 1969:104).

Newcombe notes: “String is made by joining strands of nettle fibre by rubbing them on the thigh and then twinning them together by means of a small spindle-whorl. Sometimes these are carved with a crest of the owner” (Newcombe 1909:37). Unfortunately, Newcombe does not give any specific examples of whorls with iconography that represents an owner’s crest.

Ethnologist Wayne Suttles noted, from information collected in the 1950s, that among the Central Coast Salish speakers:

“Weavers also made a fabric of yarn produced by mixing waterfowl down with nettle fibers, and they made pack straps by twinning on suspended warps, incorporating some of the design elements seen in the blankets” (Suttles 1990:462). There is no mention here of the size of the spindle.

Suttle’s First Nations consultant Julius Charles (born about 1865. Father Semiahmoo and mother Lummi) noted that during winter hunting men wore a buckskin jacket over a bird down and nettle fibre undershirt (Suttles 1974:262-265).

During his field research in Washington State in 1925-27, Olson interviewed five Quinault First Nation consultants that were all over 60 years old, with one, Bob Pope, being over 90. Olson was informed that there were four sizes of nettle thread. Netting was made from two of these threads spun together. The same method was used for the Mt. goat and yellow cedar (Olson 1936).

“The familiar rabbit skin blanket of western North America was also made. The skins were cut into strips and these twisted hair side out, a spindle being sometimes employed. The strips were either woven as a simple cross weave or, probably more usually, used only as the warp, the weft consisting of elk sinew threads twined in at intervals. The skins of ducks were sometimes cut into strips, which were twisted and woven in the same fashion as the strips of rabbit fur” (Olson 1936:82). No mention is made if different sizes of whorls were used for the production of different materials.

Olson refers to the sheared dog hair being placed into “a cleft stick to keep the hairs aligned”. Here he clearly describes the use of the larger whorls:

“Twisting of this hair into yarn was done simply with the fingers (Pope) or by means of a spindle which was rolled down the thigh. The spindle was eight inches or so in diameter (210-220mm). A third informant stated that a spindle (without whorl) which had a hook at its tip was used to pick up the tufts of hair out of the split stick, the spindle being merely twisted by the fingers of the right hand. The yarn was then rolled into balls. Few (or none?) blankets were woven with both the warp and weft of this yarn, twisted elk sinew being woven or twined in as the other element” (Olson 1936:82).

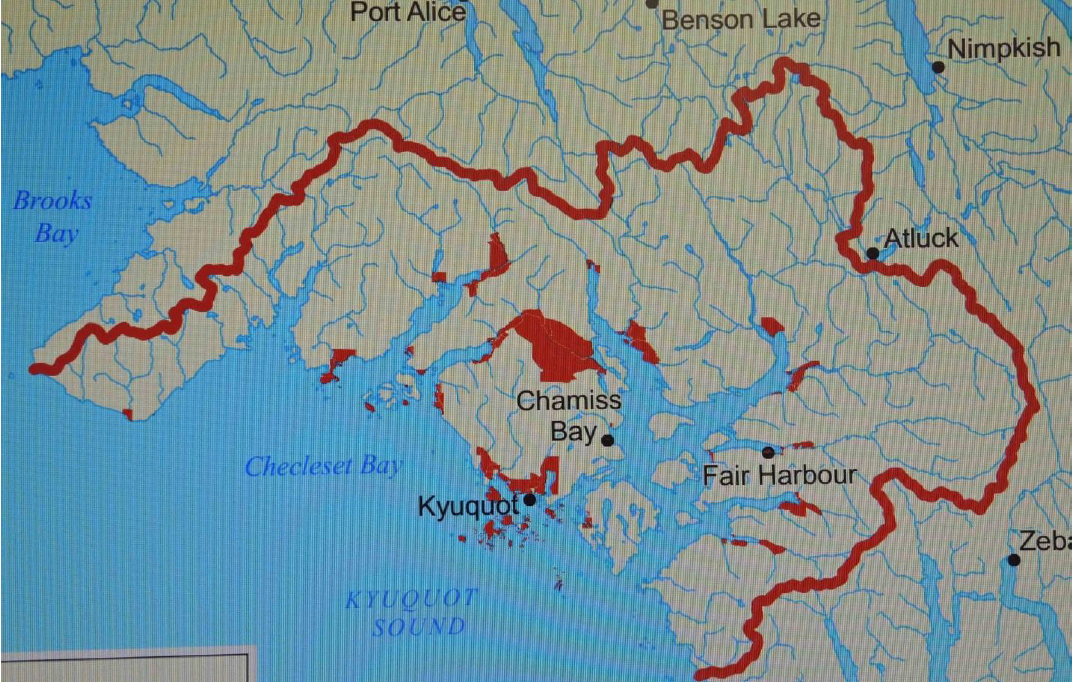

Nuu-Chan-nulth of the West Coast of Vancouver Island

It is unclear whether small spindles were being used among some Nuu-Chan-nuth peoples in 1792. Don Francisco Mosino observed the women at Yuquot “are mainly engaged in the sedentary occupations of spinning and weaving”. But he then suggests that they do not have spindles in his reference to “distaffs”. He points out that: “They have no distaffs except their teeth and fingers, with which they bind together cypress [cedar] fibre and otter hair in order to form a thick plait. This they then make thinner and longer, until they have a skein about a foot long. They use the most simple looms, making a warp out of a cane set horizontally at a height of four and a half feet from the ground; they move their fingers along it rapidly in different directions and with extraordinary skill, making up in this way for the lack of tools which would in any other case be necessary and indispensable for this work.” (Jane 1971:107).

Drucker, working among the Nuu-Chan-nulth (1951:94), notes that after beating cedar: “A part of the strands were woven into thin cord to be used in weaving the robes, rain capes, and women’s aprons. Spinning of this, and all other cordage, was done by hand, on the bare thigh. Spindles have not been used within the reach of modern folk-memory. Several informants recalled having seen Nitinat women spinning with large wooden spindle whorls, apparently like those of the Coast Salish. Presumably the practice of spinning with small bone and stone spindle whorls went out of use very early.”

The observations of Nitinat women using large spindle whorls is interesting in light of the suggestion that the Nitinat, or at least some of them, once spoke a Salish language (Drucker 1951:94). In 1861, a settlement of “Cowichan” were recorded as living “near San Juan harbor”. The British Colonist reported that: “Some years ago this tribe was a very numerous one, but through wars and disease it has been reduced to only twenty men and women” (The British Colonist, March 9, 1861:3). Chief Charlie Jones told the story of how people from Cape Flattery “took over Nitinat Lake for a period” before the coming of Europeans (Arima 1983:105).

The Iconography on Small Spindle Whorls

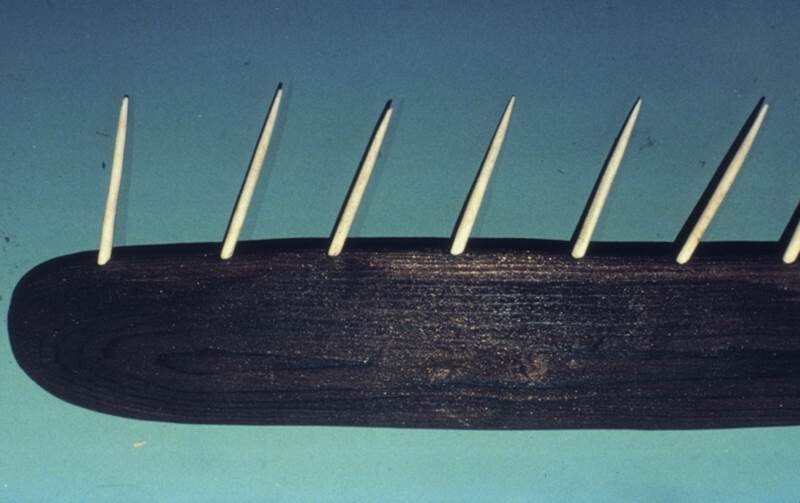

Figure 3. Small carved bone whorl (after Miles 1969:186 fig. 7.146).

There are few small spindle whorls in ethnographic collections with designs of any kind. Unique examples include one collected in 1893, by Adrian Jacobsen at Bella Bella (old RBCM #454). It has a frog on one side and what is described as a “mountain spirit” on other side. The “mountain spirit” has a human-like face with round eyes, heavy eye brows and raised cheeks. A Nuu-chan-nulth example (figure 2) collected by Boas in 1886-1897 shows a squatting whole human figure, but no interpretation of the image is given. Like some later images on large whorls of speakers of Salish languages of Vancouver Island, the hole for the insertion of the latter spindle is centered in the body of the human figure. A unique design can be found on a whale bone specimen (on a short spindle) from a private collection pictured in Miles (1963:102 & 186). It is a more stylized modernistic image (figure 3) that may represent a bird head with the hole representing an eye, or it is a combination of symbols. Miles describes this “Northwest Coast nettle fibre spindle” as having a “design Haida in character”.

It is interesting that geometric designs exist on small pre-contact stone and bone whorls from locations on the south coast and into the southern Interior but are not found as ethnographic examples.

The Ethnology Collection

Nisga’a

RBCM 1692 A,B – (with spindle A); (old #480). Nisga’a. Gitkateen. Lakalsap. Whorl: Wood. Flat. Diameter: 79-81mm; th. 9-9.3mm; hole dia, 12mm. Weight: 16.6 grams. Flat edge irregularly cut. There are two small nails in the edge on opposite sides of the whorl used for the purpose of strengthening the crack across the centre of the whorl. Purchased by Charles Newcombe in 1912. Newcombe notes: “Spinning wheel Lagiauks, spindle turned by right hand on right leg. Rest stick Watuqs”. Spindle: L: 377mm; Thickness: 10mm near center; Weight: 14.5 grams. Whorl is removed from spindle but originally near center.

RBCM 1693. Nisga’a. Stone. Large hole. Four carved oval eyes on one side. Weight: (not available). On artifact “1088”; “26 (?) 13”. Lakal? “Mark Tait, Skimmer for (BD?) GR Equals Hadaq 2.00, whirl of stone equals Hagia KS 2.00 NTBK 29A. Purchased by Charles Newcombe in 1913 from Mark Tait. Lakalzap. Greenville, Naas River”. Transfer to Nisga’a First Nation (No image).

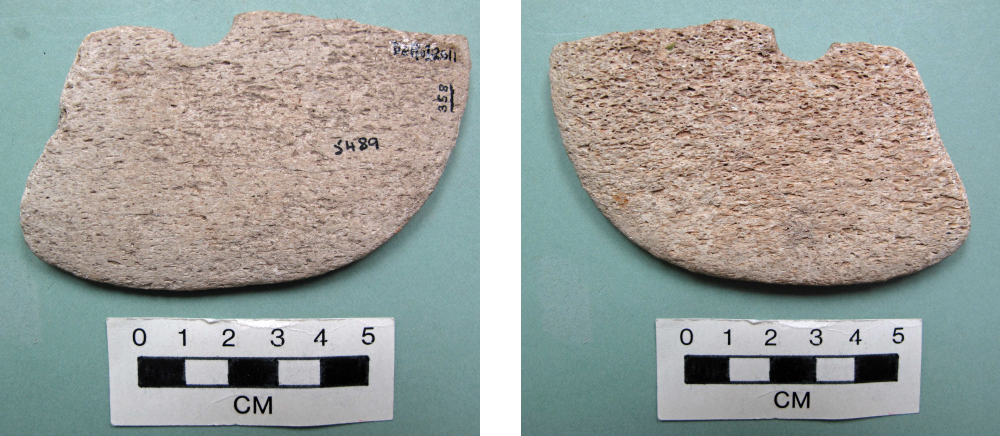

RBCM 15908 B – (with spindle A), Nisga’a. Lakalsap. Gitkateen. Sea Mammal bone. Flat edge. Whorl: dia. 69.5-71mm; th. 9.5-13.5mm (thicker toward middle); hole dia. 11mm; Whorl Weight: 32.3 grams. Whorl positioned 21cm from one end. Spindle L: 478mm; Weight: 29.5 grams. Purchased in 1977 from Queensway Trading in Terrace, B.C., who purchased it earlier from Mr. Sam Green of Greenville.

Haida

RBCM 9963a&b. (with spindle) (old #963). Bone. Near flat disc. Slightly concave on both sides. Weight: 45.9 grams. Diameter: 83 by 84mm; hole diameter 13mm. Thickness: 4mm on outer rim to 7mm near inner hole. Spindle, wood. Length: 430mm. Thickness: maximum 13mm. Collected by Charles Newcombe in Masset, Oct. 1, 1913. (Newcombe Family papers. Add. Mss. 1077. Vol. 40, Folder 7. Subject Files, Series B: Collections. Photo by Newcombe, Nov. 1917, EC575 glass plate). Collected in 1913. From estate of William Newcombe 1961.

Haisla

RBCM 2066a,b. (with spindle); “Kitimat”. Wooden whorl. Maple? Diameter: 88.2X94.4mm; pencil line circle inside 73X77mm; th. 11.8X16.5mm (thicker near middle), whorl centered toward one end on spindle; hole dia. 11mm (slight burned area in hole). Edges flat and roughly carved. Spindle of Cedar. Length: 530mm; Thickness: 112.5mm. Weight: 64 grams. Whorl located 18cm from one end and fixed on spindle. Weight of spindle and whorl: 64 grams. Collected by Charles F. Newcombe in 1911 from Mrs Robinson of Kitamaat.

RBCM 2067a,b. (fixed on spindle) (KW) “Kitamaat”. Sea mamal bone. dia. 59.5mmX65mm; th. 80-89mm; hole dia. 12mm. Spindle of cedar: L: 523mm. Thickness: 13.5mm. Whorl 230mm from one end, near center. Combined weight of whorl and spindle: 57.8 grams. Charles F. Newcombe 1911.

Heiltsuk (Bella Bella)

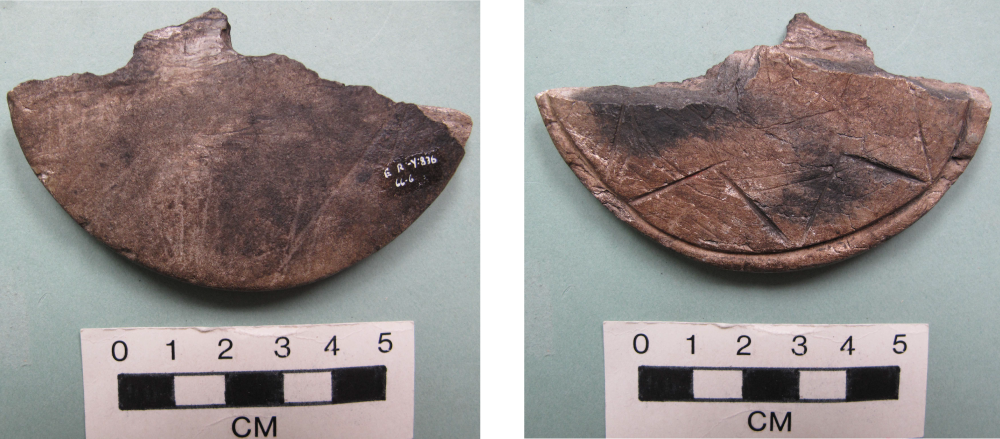

RBCM 449a & b – (with spindle) Bella Bella. Sea mammal bone. (1893, F. Jacobsen) diameter 62.7X65mm across hole. Broken. Whorl position off centre. th. 8mm; hole dia. 9mm. Whorl fixed on cedar spindle, combined weight 49.8 grams. Spindle L: 32.4 (small portion of end broken); Width: 8.6mm. Preliminary Catalogue 1898: “Wooden spindle, with bone whorl and native wool”.

RBCM 450a & b – (with spindle) Bella Bella. (1893, F. Jacobsen); Sea mammal bone. Flat body and edge. dia 71-77mm; th. 8.3-8.8mm; hole dia. 11mm; Spindle L: 550mm; Th: 10.3mm. Whorl fixed on spindle. Combined weight: 62.3 grams. [Recorded in 1898 catalogue, p. 164].

Bella Bella spindle and whorl. RBCM 450&450b.

RBCM 451 (with spindle). Bella Bella. (1893, F. Jacobsen); sea mammal bone. Flat whorl; Edges flat with rounded corners; dia. 60X63mm; th. 5.9 – 6.4mm; hole dia. 11mm. Spindle: L 545mm; Th: 11.2. Whorl centered at 280mm. Combined weight of whorl and spindle: 51.8 grams.

RBCM 452a & b. – (fixed on spindle). Bella Bella. Sea mammal bone; dia. 58.8X59mm; th. 95mm; hole 11mm. Cedar Spindle: L: 410mm; Th: 10mm. Whorl 160mm from one end. Combined weight of whorl and Spindle: 48.9 grams. Whorl fixed on spindle. Collected in1893 by F. Jacobsen.

Bella Bella Spindle and whorl. Ethnology RBCM 452a&b.

Bella Bella spindle whorl. Mountain Spirit design. RBCM 454.

RBCM 454 – Listed in Old Catalogue as “Kwakuitl”. “Carved bone whorl. “Frog on one side, mountain spirit on other”. “A. Jacobsen 1893, Bella Bella.” Acquired April 1909. The 1909, Guide to Anthropology Collection in the Provincial Museum repeats this information on page 37: “No. 454 has a frog on one side and a mountain spirit on the other”. The label of Newcombe’s Lantern Slide, EC374, has “Bella Bella Spindle whorl” on it. This artifact was stolen when on loan for an exhibit in Vancouver in 1936. A poor quality caste is located in the archaeology collection as Y-806 (75-7). The connection with this and #454 had been lost until now. The cast is nearly flat: Diameter: 67-68mm. Thick: 7.0mm at center and 6.5mm at the edges. Hole diameter: 10mm. Black and white photograph #22603. The “mountain spirit” has a human-like face with round eyes, heavy eye brows and raised cheeks. Newcombe EC374 “glass plate”, 1909 – copied as PN 1337 – shows the same image. Photograph 721 shows the frog design from Newcombe’s 374-IX/69, 1909, and a different version of the same frog image in photograph 721-A – listed as EC 374 – IX/69, 1909.

Nuxalk (Bella Coola)

RBCM 2978 – (fixed to spindle) Bella Coola. Wooden whorl. Dia. 76X82mm; Th. 12-19mm (thickens toward middle); hole 10mm; Hardwood Spindle. L: 440mm; Th: 10mm. Whorl near middle of spindle. Combined weight of spindle & whorl: 59.5 grams. (purchased from Capt. Schooner, 1917); (in image PN11455).

Bella Coola Spindle and Whorl. RBCM 2978.

RBCM 9986 – (moveable on spindle); Bella Coola; sea mammal bone, flat. Dia. 66X68mm; th. 12-14.5mm; hole 10mmm; Flat edge with 3mm inset low area; Weight: 26.5 grams. [1914, ex Gibson coll. “Bought at Van. Canadian Handicraft Guild 6/8/14”, then into Newcombe collection; old # 986]. Spindle: L. c400mm; Whorl positioned mid-way, c, 200-210. Spindle weight: 16.2 grams. Old #986. Pencilled at center of spindle: “Spindle Ex… Gibson. 1914”.

Bella Coola RBCM 9986.

RBCM 10112 – (fixed on spindle) Nuxalk; Flat sea mammal bone. Dia. 49-51mm (squarish); th. 11.0-12mm; hole dia. 9mm. “Bella Coola” in ink on one side. Old # 1112. Cedar spindle. L: 515mm; Th: 9mm. Positioned between 260mm and 270mm on spindle. Combined weight of spindle and whorl: 43.0 grams. Newcombe, June 1917. Newcombe photo EC575. Nov. 1917.

Spindle and Whorl RBCM 10112.

RBCM 10113 – (no spindle) Bella Coola; Flat sea mammal bone. Flat edge with rounded corners. Weight: 33.8 grams; dia. 65-65.9mm; th. 6.5; hole dia. 12mm; Slightly burnt. Newcombe collection, old # 1113, glass plate photo, Nov. 1917, EC575.

Kwakwala Speakers

RBCM 2068 – (no spindle); Alert Bay. Sea mammal bone. Weight: 71 grams; dia. 67.1X69mm; th. 14.1-14.4mm; hole dia. 13mm. (old C.F. Newcombe #359. Collected in 1912).

RBCM 2069 (no spindle); (KW); Sea mammal bone. Weight: 25.4 grams. dia 55mm; th. 6.6-7mm; hole dia. 11mm; (19-21mm radius shift from edge of hole). Flat with flat edges. (old C.F. Newcombe #360 collected in 1912).

RBCM 2070 – (no spindle); Alert Bay; Sea mammal bone. Weight: 19.7 grams. Diameter: 47X48mm; th. 6.1-6.3mm; hole dia. 9mm; Flat with flat edges. (old C.F. Newcombe #361, collected in 1912).

RBCM 6530 – (with spindle) (KW); Sea mammal bone. Diameter: 58X62mm; th. 8X8.2mm; hole dia. 8mm. Combined whorl and spindle: 48 grams. Fixed Whorl, located 15cm from one end of spindle. Spindle: L. 406mm; Th: 8.2mm. Acquired 1947. “Spindle with whale bone whorl for nettle fibre plain”. “Canon A. J. Beanlands Coll. Per Mrs. Alyson N. Beanlands. Collected about 1884-1909”.

Kwakwala. RBCM 6530.

RBCM 10090a, b. (with spindle) (KW); Sea mammal bone. Diameter: 63.4X65.2mm; th. 6.1- 6.6mm. Hole dia.: 11mm, Whorl weight: 8.9 grams. Slightly burnt by design. Cedar spindle. Whorl centered on Spindle. Spindle: L. 343mm; Th: 11mm. Kingcome Inlet. Old # 1090 written on center spindle under hole and on flat of whorl.

RBCM 10448 – (no spindle) “Fort Rupert, Tsaxis”. Sea mammal bone. Diameter: 59mmX61mm; th. 6-6.5mm; hole dia. 11mm. Weight: 22.9 grams. [old #1448].

RBCM 10448. Kwakwala.

Nuu-chan-nulth

Stone Whorl. RBCM 12691.

RBCM 12691 – (no spindle); Quatsino. Grey Slate. dia. 72mmX73.8mm: th. 6.9-7mm; hole dia. 10mm. Painted red, green and black. Made with steel file. Two incised circle grooves on painted side. Whorl off center. Weight: 59.7 grams. No design on one side. Modern non-traditional whorl. It was likely made as a model for sale.

Comments on some Ethnographic and Historic Accounts

There are many references to spinning that can refer to spinning by twisting fibre by hand on the knee or references that do not specify the size of the spindle whorl. In a prospecting tour of the north coast James McKenzie notes that going up the Nass River he passed five villages during which he observed the spinning of “goat hair garments for women” without mentioning the use of a whorl (McKenzie 1864:3).

Morice observed in 1892-93 that: “rabbit skin blankets were originally the only genuine textile fabric manufactured among “the Carriers, the Tsekehne or the Tsilkohtin”. Strips of rabbit skin were tied together and twisted on the thigh, and used as both warp & weft stands on a frame, but he notes that the Carrier did not use a spindle and whorl. He does illustrate a spindle with a whorl used by the Chilcotin, but does not indicate if it is small or large one (Morice1892:156).

Further south along the Columbia River-Upper Arrow Lakes region on May 7, 1814, Gabriel Franchere observed: “Natives camped on the bank of the river” – “The women at this camp were busy spinning the coarse wool of the mountain sheep, They had blankets or mantles woven or platted of the same material, with a heavy fringe all round…”. Near Rocky Mt. House Franchere notes in reference to “Mt. Sheep wool”, that: “The Indians who dwell near the mountains make blankets of it, similar to ours, which they exchange with the Indians of the Columbia for fish and other commodities” (1968:231-32; 216). No mention is made of the use of a whorl.

One of the more extensive commentaries on spinning, weaving and their similarity between the Fraser Canyon and the Lower Fraser River was made in a 1908, letter from James Teit of Spencer’s Bridge where he refers to blankets from Spuzzum that the daughters of Joseph McKay (of the HBC) were trying to sell to the Provincial Museum. It appears that the commentary here refers to the larger whorls being used in the Fraser Canyon area:

“I intended writing you before, but was waiting another chance of interviewing the Spuzzum woman. I saw her again a few days ago. She says she never saw a loom exactly like the one in Nootsack, and are different from the ordinary large blanket loom, the horizontals being different and not made to turn, and the head band is made in a simple piece stretched up and down, and not over the horizontals. (The only way to get a proper idea of this kind of loom will be to have one made). As I am going to Vancouver …on my way back I will try to stop off at Spuzzum and get one of these small looms. She said she never heard of any combs being used. The weaving being done with the fingers. Re: the breed of dogs she says the pure breed was totally extinct around spuzzum before she can remember, but she has heard from the old people they were a medium sized animal with long and very fine thick hair. They were mostly white but some it is claimed were black. They were a distinct species according to tradition introduced from the Lower Fraser, and were to be found nearly as far East as Lytton. The Indians tried to keep them from inter-breeding with the real Interior dog, and around Spuzzum favored the keeping of them rather than the former. Their hair was used in blanket weaving at Spuzzum, generally mixed with the wool of the goat. People who did not have any of these dogs used only goat’s wool. The using of dog’s hair it is said made the blankets of a softer texture & furthermore they supplied a source of wool right at hand, whereas the goats had to be hunted and their wool thus cost considerable labor.

These dogs were of altogether a different species from the common dog of the Thompson further east and were called by the special name of xlitselken. The other dog called skaxaoe (viz real dog) somewhat resembled the husky and also bore some resemblance to the Coyote and to the wolf with both of which they occasionally inter-breed. They were used mostly for hunting purposes. Re: the dyes used with blankets etc. The common colors were yellow, red & black. Yellow was obtained from Wolf moss (evernia vulpina I think is the botanical name) red from alder bark, and black bear’s hair for black. The hair of black dogs was also used when obtainable viz black specimens of xletselken. She has however heard of the following dyes also being used viz red ochre (giving a reddish tint) roots of oregon grape (yellowish) berries of the cedar (greenish), Possibly other dyes like those used amongst the Upper Thompson may also have been used, but she does not know. The ring you speak of as being used to keep up tension when the Weaver was spinning the loose wool on the spindle I have seen in use on the Lower Fraser. They were made of both wood and stone. I saw a lot of stone ones at Musquiam village, and at several points on the Lower Fraser Indians told me these stone rings were used for this purpose of course the wooden rings were much more common. As to judge from your description of Mrs. McKay’s blankets it is very unlikely the material is dog’s hair, and the dyes native. I think this is all I can tell you about these blankets at present – the weaving, and the preparing and spinning of the wool was just the same at Spuzzum as on the Lower Fraser & southern coast. I would like to keep the prints you sent me if you do not require them. …I sent a specimen of the earth (in prepared state) used for cleaning or taking the oil out of the wool to the Amer. Museum. …” (Teit 1908).

Summary Commentary

It is important to discuss the differences between small and large spindle whorls, as they often have different uses and different regional histories. Where spindle whorls came from is still a question waiting to be answered. Bone spindle whorls have been found in archaeological sites stretching from the American gulf Islands to the central coast of B.C., but their dating is unknown or their placement is within broad time periods. For example, King notes a spindle whorl in the Maritime phase of San Juan Island with a broad time frame of 500 A.D. to 1500 A.D. and suggests that: “The occurrence of a spindle whorl in the Maritime strata in conjunction with the needles and the remains of small dogs, mountain sheep, and mountain goat makes it highly probable that the Maritime phase may mark the beginning of the weaving of wool and hair in the southern Northwest Coast area” (King 1950:81). As in other cases, the spindle whorl could date to the last centuries of the time sequence given.

There are no solid examples of small spindle whorls dating before about 600 years ago. Carlson (1971) indicates that the three whalebone whorls from the Kwatna Inlet site FaSu-2 are of the late period from A.D. 1400-1800. Small stone whorls of a pre-contact age with geometric designs appear in the Fraser Canyon, but historic period references pertain to the larger whorls common on the southern coast in the historic period.

In Mesoamerica we see the establishment of ceramic and stone spindle whorls by the late Preclassic period 400-250 B.C. and early Early Classic period 250-600 A.D. and their considerable expansion by the Late Classic period 600-900 A.D. In Mexican spindle whorls (particularly the larger whorls for spinning maguey fiber) were decorated with incised and mold-made designs, but the production of decorated whorls stopped during the 16th century (Brumfiel 1997). The influence of spindle whorls appears to have spread from Northern Mexico to the American Southwest where small spindle whorls appear in the Pecos culture of New Mexico around 1100 A.D. and spread throughout the American Southwest. The latter were made of bone and ceramic with the bone examples mostly in the 5-10cm diameter range (Kidder 1932). More precise dating of spindle whorls in British Columbia is needed to tell the story of when and where they came from and the economic and social context of how they diffused over the landscape under various cultural trajectories.

Bibliography

Arima, E.Y. 1983. The West Coast (Nootka) People. British Columbia Provincial Museum Special Publication No.6.

British Colonist. 1861. The Squaw Murder. The British Colonist, March 9, p.3, Vol. 5. No. 69.

Brumfiel, Elizabeth M. 1997. Tribute Cloth Production and Compliance in Aztec and Colonial Mexico. Museum Anthropology. Journal of the Council for Museum Anthropology, 21(2)55-71.

Carlson, Roy L. 1971. Excavations at Kwatna. Anutcix (FaSu-1) and Kwatna Phase sites. FaSu-1 and 2. Late prehistoric A.D. 1400-1800. Salvage ’71. Reports on Salvage Archaeology Undertaken in British Columbia in 1971. Edited by Roy L. Carlson. Department of Archaeology, Publication No. 1. Simon Fraser University, Burnaby British Columbia.

Drucker, Philip. 1951. The Northern and Central Nootkan Tribes. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 144. United State Printing Office, Washington,

Franchere, Gabriel. 1968. (Ed. Milo Milton Quaife). A Voyage to the Northwest Coast of America. Citadel Press, New York. pp. 231-32; 216.

Jane, Cecil (Editor). 1971. A Spanish Voyage to Vancouver and the North-West Coast of America. N. Israel/Amsterdam. Da Capo Press. New York.

Kidder Alfred Vincent. 1932. The Artifacts of Pecos. New Haven. Robert S. Peabody Foundation for Archaeology. Yale University. Pp1-314.

King, Arden. 1950. Cattle Point A stratified Site in the Southern Northwest Coast Region. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology. Number 7. Published Jointly by the Society for American Archaeology and the Tulane University of Louisana. Menasha, Wisconsin, USA. Supplement to American Antiquity, Vol. 15(4), part 2, April 1950.

McKenzie, James. 1864. Prospecting Tour of the North West. Victoria Evening Express, September 9, 1864:3).

Miles, Charles. 1969. Indian and Eskimo Artifacts of North America. Bonanza Books, New York.

Morice, 1892-93. Notes on the Western Dene. Transactions of the Canadian Institute. Vol. IV.

Olson, Ronald. 1936. The Quinault Indians. University of Washington Publications in Anthropology. Volumne VI, Number 1. University of Washington Press. Seattle and London.

Suttles, Wayne P. 1990. Central Coast Salish. Handbook of North American Indians – Volume 7: Northwest Coast, William C. Sturtevant General Editor, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, pp. 453-475.

Suttles, Wayne P. 1974. Coast Salish and Western Washington Indians 1. The Economic Life of the Coast Salish of Haro and Rosario Straits. Garland Publishing Inc. New York.

Swan, James G. 1969 (1857). The Northwest Coast. Or, Three Years’ Residence in Washington Territory. University of Washington Press. Seattle and London.

James Teit. 1908. Letter of January 3, 1908 to Charles Newcombe. Newcombe Family Files, RBCM Archives.

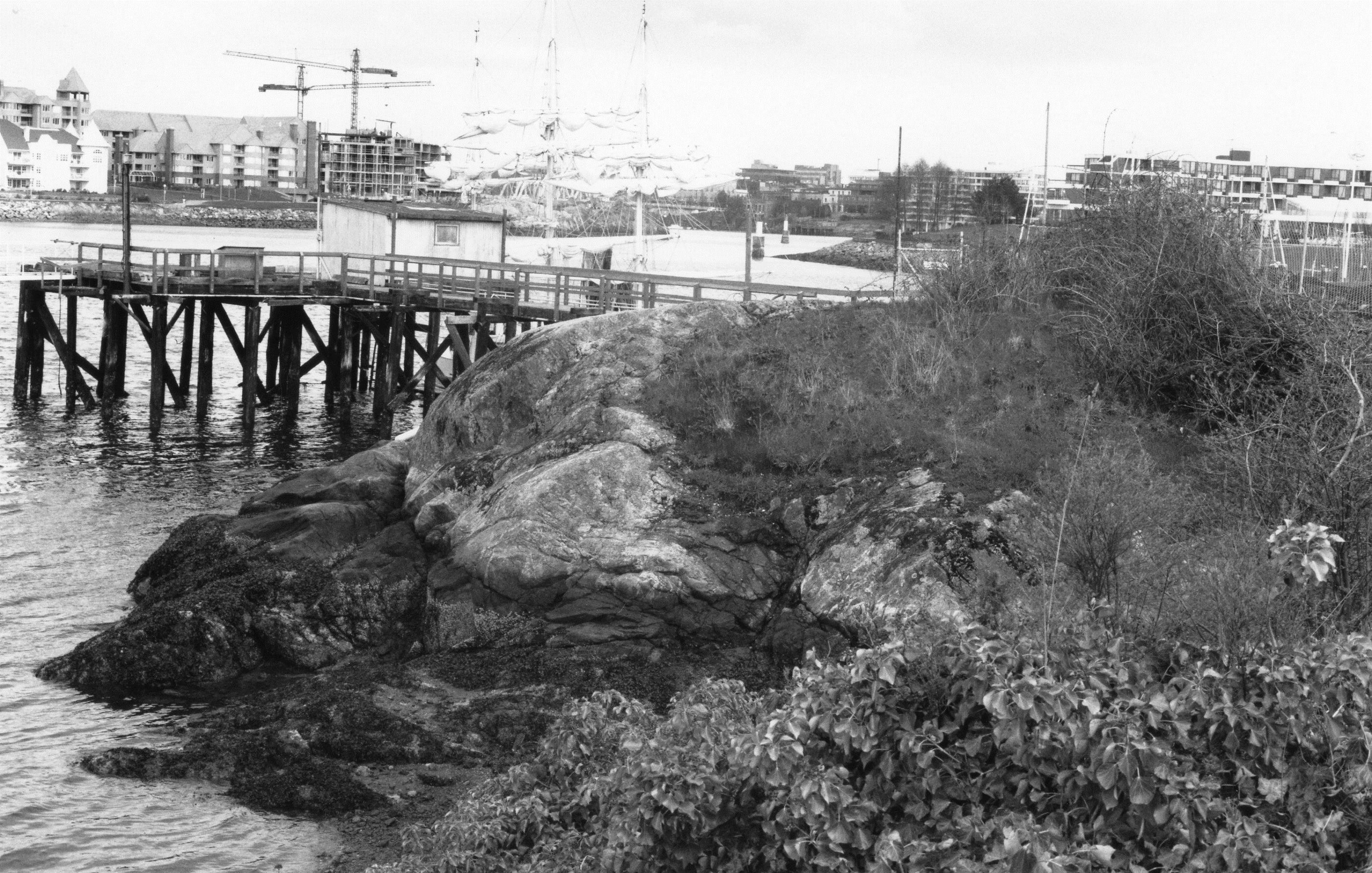

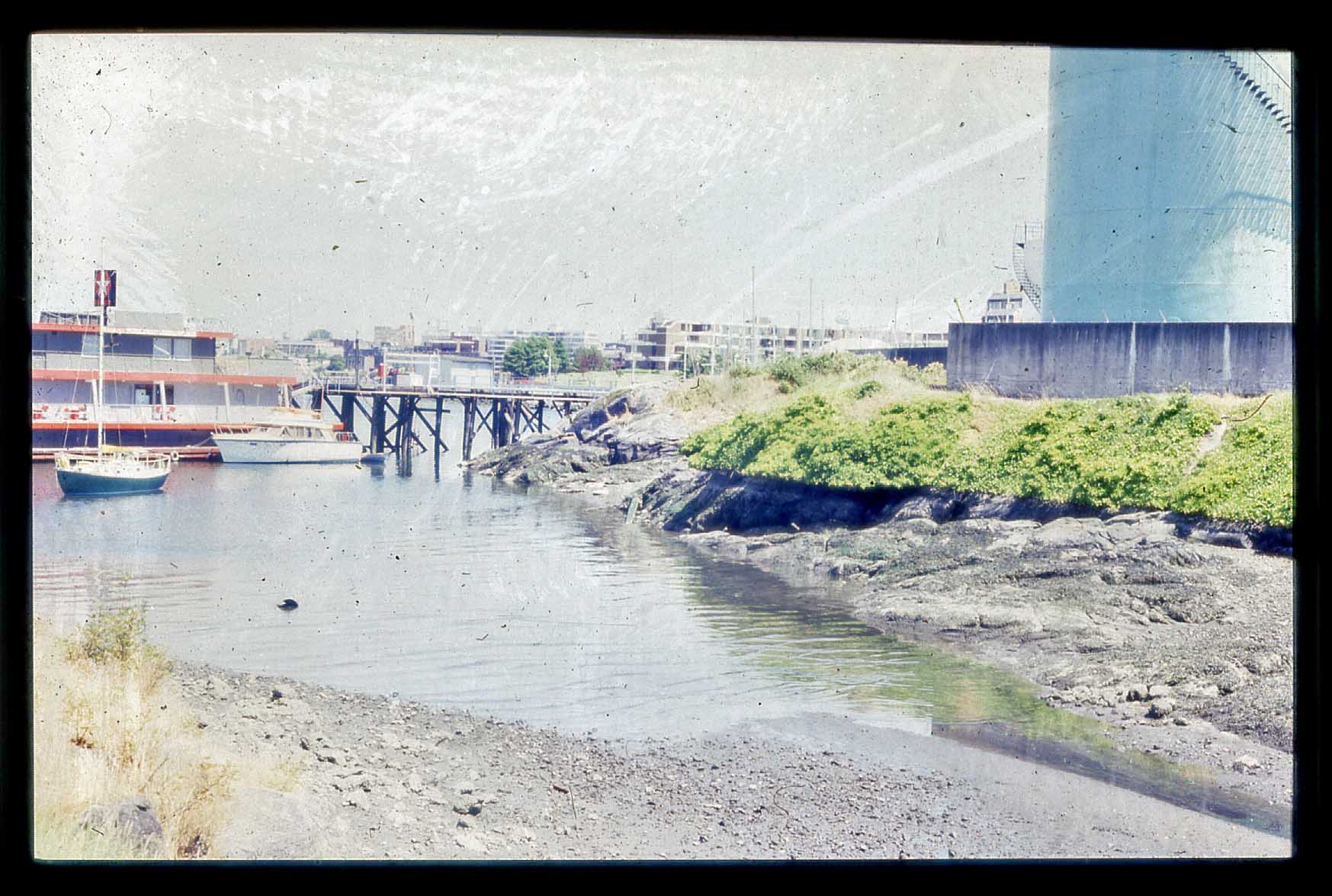

The remains of an ancient village, in the form of a shell midden, are located around the intersection of Store and Chatham Street off Victoria’s upper harbour. The site, listed as DcRu-116, was on a rocky bluff on the east side of the Harbour between the Johnson Street and Point Ellis (Bay Street) Bridges. This specific location on a rocky bluff with a good view up the Harbour would suggest the site was chosen for defensive purposes.

Figure 1. Capital Iron building on the right foreground, 2017.

Archaeological Excavations

Figure 2. 1976 excavation of pit 2 looking N.W. The author Grant Keddie taking measurements with Jim Pike of the Archaeology Branch. Tom Bown excavating. John McMurdo of the Archaeology Branch standing. Don Abbott Photograph. 1976.

Figure 3. Excavation pits looking north. Ray Kenny and Bob Powell in unit 1. Jackie Cornford above second pit, with Grant Keddie, Jim Pike and Tom Bown excavating with trowels. Don Abbott Photograph. 1976.

In 1976, buried shell midden was discovered during the removal of massive amounts of overburden for building a new facility next to the Capital Iron building at 1900 Store Street. On an emergency basis, volunteers from the (then) Provincial Museum and the Archaeology Branch spent the weekend of April 10-11 recovering information from this site. After removing over a meter and a half of disturbed overburden we encountered partially intact and then intact cultural material. We excavated to the base of the midden, which extended to a depth of 110cm, before we encounter non-cultural material below. Two excavation Units were each approximately 2 meters square and measured from the N.E. corner of the main building adjacent to the pits. Pit 1 was located North 8m – 9.8m and East 18m – 20m from the main datum. Pit 2 was located North 10.2m – 12m and East 18m – 20m. A 40cm bulk was left between the excavation pits (See figures 2-4).

The midden extended north from the Capital Iron building for 24 meters, but was visible under Store Street for 40 m north of the main building. The upper levels of the excavation units were disturbed with a mixture of non-indigenous artifacts and older shell midden – especially in the first two levels. Excavation started in level one at 10-20cm. This level contained mixed historic materials – coal, glass, slag, window and bottle glass (one square green whiskey bottle with applied top), round headed copper nails, five square-headed cut iron nails and round thick headed nails and spikes. Level 2, at 20-30cm, contained smaller amounts of square nails, bottle glass and ceramics from the late 19th century. Level 3 at 30-40cm contained only one iron spike, a few square headed nails and portions of a few dark glass pantile based bottles.

What was noticeable in level 5 (50-60cm) in Unit 1 and level 6 (60-70cm) in unit 2 was the large quantities of herring bones and scales. An occasional piece of burnt wood and a few square headed nails protruded into portions of level 5, but levels below to the base of the cultural deposits (80cm in Unit 2 and 120cm in Unit 1) were in tack. The predominant mollusks observed were native oyster with much smaller amounts of native little neck, butter, cockle and horse clams as well as bay mussel, whelks and barnacles.

Figure 4. Looking east at two excavation units with cut soil profile below. Capital Iron building in background. Art Charlton, from the Archaeology Branch standing. Don Abbott Photograph. 1976.

Figure 5. DcRu-116 location seen from the water. The Capital Iron Building is on the far left. Hope Point is on the Victoria West side on the far right.

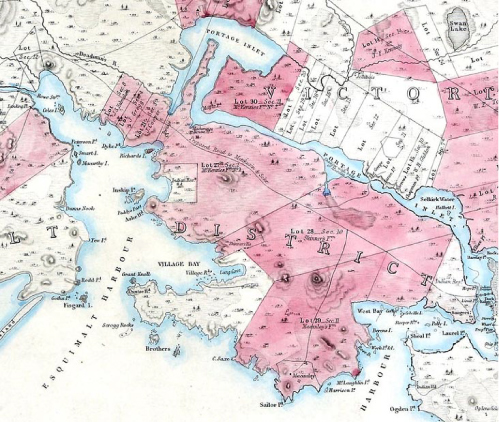

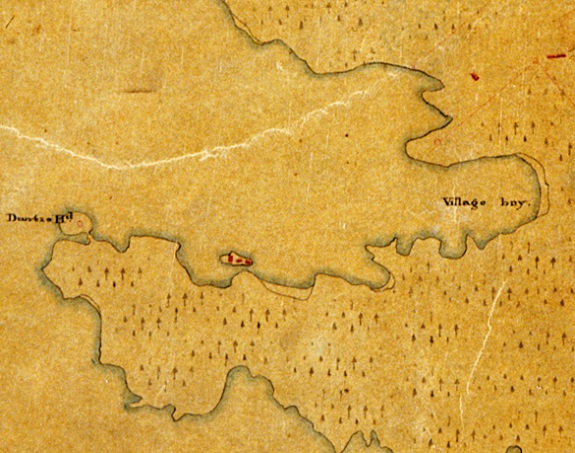

A water source was available for people living at this site from a creek that ran down the Haultain valley into Rock Bay to the North (see figure 6 & 7). This can be seen in a portion of Joseph Pemberton’s 1852 detailed map of the west side of Victoria Harbour (figure 6). Many historic activities have altered the landscape in this area (see Appendix I).

Figure 6. Site DcRu-116 seen on an 1852 map. Johnson Street Ravine on the right.

Figure 7. Portion of 1863, map showing the relationship of site DcRu-116 to the upper harbour, Rock Bay and the south end of Selkirk Waters.

Dating the Site

The charcoal sample I extracted from the lower intact deposits of this site was radio-carbon dated to an uncorrected date of 1690-+70 (Beta 59892). The Calendric Age is calBP: 1608+or-82. 68% range calBP: 1526-1690. Calendric Age cal:342+/-82. This would place the bottom deposits of the site in the calendar date range of around 260 to 424 A.D.

There are few sites in the Victoria region that have dates in this time range. This period is missing in the large DcRu-12 shell midden on the Songhees Reserve in Esquimalt Harbor. There is, however, a partial overlap of the date range from the bottom of DcRu-116 with the bottom of the shell midden, DcRt-9, in Cadboro Bay which has a time range of 138 to 388 A.D. (Keddie- RIDDL571). There is also a partial overlap with the bottom of the main shell midden deposits at the large defensive site on Ash Point in Pedder Bay with a bottom range of 373-581 A.D.

Because of disturbed upper deposits I could not determine if this site was occupied in late pre-contact times. The small map, drawn by John Woolsey in 1859, (See Keddie page 46) shows houses as being “Songhees”. These could be construed as being in the area of shell midden, DcRu116, but the Woolsey map is not detailed enough to place the houses at this location with any certainty. There is no recorded tradition of a village at this location.

DcRu-116 artifacts.

There are 133 artifacts from this site. This assemblage includes artifacts recovered from an emergency excavation undertaken on the weekend of April 10 and 11th 1976, by staff from the Royal B.C. Museum and the Archaeology Branch. Nine of the artifacts were from disturbed surface midden deposits at the site and 30 artifacts were found in a large amount of shell midden mixed with other materials from this site that was dumped on April 9th at a location off Kimta Road in Victoria West. Tom Bown and I visited the latter location on a number of occasions to recover artifacts in the washed out material. I examined the excavation level bags, with their recorded site provenience, in November of 1992 and identified artifacts #59-132.

There were two excavation units established with a 40cm wide bulk in between. Unit 1 or Pit 1 was located at North 8m-9.8m, East 18m-20m. Unit 2 or Pit 2 was located at North 10.2m-12m, East 18m-20m. Both were dug down to the bottom of the cultural material. The main datum and unit or sub-datums were the same at this site. The main datum was a point on the then existing building wall, with the two excavation units marked out in meters north from the wall. I intentionally made the main datum to be level with the N.W. corner of each excavation unit in order to make the depth of each of the units easily comparable.

Artifact Descriptions

The artifacts are described here under classes and sub-classes that reflect different kinds of human behavior. The class Wealth, Status, Ceremonial is represented by only one artifact here. The class Subsistence is related to the procurement and processing of food. Tool Making refers to fabrication equipment that includes implements primarily used in the alteration or assembling of raw materials for use in the various stages of manufacture of other implements or equipment, and the waste material from these activities. This latter class includes the majority of the artifacts from this site.

Class: Wealth, Status, Ceremonial

Figure 8.DcRu-116:67. Ground deer phalange artifact.

DcRu-116:67. Shaped, deer phalange. Use unknown. This is a one-of-a-kind bone object. A deer phalange is heavily ground and tappers to the distal end. The proximal end of the bone is ground flat and the bone hollowed out. The open distal end is 0.5cm in diameter and ground around the edges. There is an intentionally made 0.3cm hole 0.5cm from the proximal base that has fractured into a larger hole. This could be part of some larger composite artifact or possibly a whistle if used with a reed. The fact that it is hollowed out would suggest that it was not intended to be used as a pendant, in which case it would likely have a notch around or a hole through the thin end. Provenience: N10-12 E18-20. DBD 40-50cm.

DcRu-116:36. Dog canine tooth. This is not an artifact, as initially recorded. The nob-like structure on the proximal end is a natural root feature. Kimta Road midden. 4.2×1.1×0.7cm.

Class: Subsistence Artifacts

Figure 9. Projectile Points. Upper left to right: DcRu-116:40; 21; 52. Lower 58;1;44.

Sub-Class: Subsistence. Hunting General.

DcRu-116:44. Projectile Point. Arrow Point. Mottled chert. Corner indented notches. Provenience: Kimta Road dumped midden.(4.6)x2.1×0.6cm.

DcRu-116:52. Triangular biface. Point for arrow or small harpoon. Basalt. Small straight sided point with incurvate base and basal thinning. Provenience: Disturbed surface at Capital Iron. 2.90×1.96×0.49cm.

DcRu-116:58. Projectile point. Point for a spear or harpoon. Basalt. Wide corner indented notches. Tip of tapering base broken off. Provenience: Kimta Road midden. 2.7×3.4×0.7cm. .

DcRu-116:40. Biface. Point for arrow or small harpoon. Basalt. Strait base and slightly excurvate sides. Provenience: Kimta Road midden. 4.35×2.5×0.7cm.

DcRu-116:21. Unfinished biface. This is a basalt biface that appears to have been broken and discarded in the process of manufacture. Minimal bifacial flaking occurs on two sides. Straight sides. Provenience: N10.2-12/E18-20 (NE Quadrant) DBU 60-70cm. (3.1)x2.85×0.5cm.

DcRu-116:1. Projectile Point. Spear or small harpoon point. Basalt. Corner indented notches. Tip of tapering base broken off. Provenience: N10.2-12/E18.11m. DBD 19cm. (4.4)x3.45×0.8cm.

Sub-Class: Subsistence. Hunting. Sea Mammals. Ground slate Points.

Figure 10. Portions of Ground Slate Points. DcRu-116:6;29;14.

DcRu-116:6. Ground slate Point. Distal portion missing and small part of proximal end. Beveled edges. N11.65 E19.3m DBU 46cm.

DcRu-116:29. Ground Slate Point. Flat proximal end. Portion of distal end missing. Beveled edges. Kimta Road Midden. (7.95)x2.3×0.5cm.

DcRu-116:14. Ground Slate Point section. A longitudinal flat piece from the side of a slate point of a much larger size.

A portion of the original ground edge is on one side. The original worked surface has 11 short cut marks and 4 ground short groves on its surface. Most of these are connected to the edge, but five short grooves are further in from the edge. N11.60 E19.92m DBD 60cm.

Sub-class: Subsistence. Fishing Equipment.

Figure 11. Fishing related artifacts. DcRu-116:8;15;7;37;18.

DcRu-116:56. Ground slate fish knife portion. No bevelled edges but the thin and very fine surface is most like finished fish slicing knifes. Disturbed surface. (5.18)x(4.75)x0.29.

Figure 12. Portion of fish cutting knife.

DcRu-116:57. Bone shank for composite trolling hook. Three small tying notched on proximal end. Groove on one side for tying bone hook on distal end. Kimta Road midden. 6.25×0.55×0.39cm.

DcRu-116:18. (DcRu-116:19 is now part of this). Bone point. Small piece of proximal tip missing. N8.86 E19.6m. In ash lens. DBU 55cm. #19 portion found in screen and recorded at 60cm DBD.

DcRu-116:37. Pointed bone object. Most likely a fish hook barb. This is the broken end of a deer ulna bone tool that has been re-worked. Fractured on proximal end. Kimta Road midden. (6.4)x0.7×0.3cm.

DcRu-116:7. Fragment of ground pointed bone artifact. Most likely a portion of a fish hook barb. N9.0 E19.90m Level III. (3.4)x1.1×0.4cm.

DcRu-116:8. Fragment of ground pointed bone. Most likely a portion of a fish hook barb. N8.0-9.8 E18-20m. DBD 40cm.

DcRu-116:15. Fragment of ground pointed bone artifact. Most likely a portion of a fish hook barb. N9.48 E19.84m DBU 51cm. (2.7)x.0.8×0.7cm.’

Class: Tool Making

Sub-class: Fabrication Tools. Adze Blades

DcRu-116:13. Adze blade. Tapered cutting edge mostly on one side. Nephrite. N8.82 E 20.31 DBD 50cm. 6.5×4.85×1.1cm.

DcRu-116:17. Adze blade. Portions of ends missing. Chlorite-like material. N8-9.8 E 18-20m. S.E. quadrant. DBD 51cm. (7.25)x4.1×1.15cm.

DcRu-116:28. Adze blade fragment. Chlorite-like material. N10-12 E 18.21m. (4.7)x(2.25)x(1.3)cm.

DcRu-116:12. Adze blade fragment. Chlorite-like material. Disturbed surface at Capital Iron. (4.4(x(1.6)x(0.8)cm.

Figure 13. Adze Blade and blade portions. DcRu-116:12; 28;17;13.

Sub-class: Fabrication Tools. Bone & Antler tools.

Figure 14. Bone and Antler tools. DcRu-116:101;9;35;51;26;10

DcRu-116:10. Antler tool. An antler wedge that has been sectioned and re-worked into a tapering point on the distal end. Could be used as a finer wedge or a fibre fabricating tool. Disturbed surface at Capital Iron. 12.1×2.3×1.7cm.

DcRu-116:26. Possible worked bone object. Mammal leg bone splinter. Water worn. May have extra use wear on one end. N 9.74 E18.33m DBD 84cm. 7.9×1.85×0.4cm.

DcRu-116:51. Spatula-like bone tool fragment. Use unknown. Heavily ground mammal rib with one end nearly complete, but split longitudinally along one side. Likely the proximal end of the unknown object. Kimta Road midden. (4.37)x(1.35)x(0.27)cm.

DcRu-116:35. Distal end of deer Ulna tool. Ground to pointed rounded tip. Kimta Road midden. (8.0)x1.4×0.3cm.

DcRu-116:9. Mid-section of the distal end of a deer ulna tool. N8.32 E20.35. DBD 40cm. (4.1)x1.9×0.7cm.

DcRu-116:101. Broken portion of a ground bone tool that has been graved to remove a section for other uses. N8-18m E18-20. DBD 0.50-0.60m. 3.8×1.5x.07cm.

Sub-class: Fabrication Tools. Abrading stones.

Figure 15. Abrading stones. DcRu-116:24;27;133;3;22.

Figure 16. Ground stone beach cobble. DcRu-116:25.

DcRu-116:39. Large abrading stone. Provenience: Kimta road dumped material. 19.3×16.0x4.6cm

DcRu-116:3. Abrading stone. Shale-like material. Portion of one end missing. Rectangular. Ground on both surfaces and sides, but very fine surface on one side with two shallow grooved areas. N8.408.55 E18.0-18.12. DBD 16cm. (14.3)x7.6×1.35cm.

DcRu-116:24. Abrading stone. Sandstone. Portion of one end missing. In tan-brown ash. Rectangular. Ground smooth on both flat surfaces and sides. N9.65 E19.48. DBD 77cm. (10.7)x5.1×1.4cm.

DcRu-116:27. Abrading stone fragment. Sandstone. Ground on both surfaces. N10-12 E19.15. DBD 80cm. (6.35)x(4.65)x2.7cm.

DcRu-116:22. Abrading stone fragment. Sandstone. Ground on both surfaces. N11.64 E19.55. DBD 64cm. (6.2)x(5.5)x1.5cm.

DcRu-116:133. Shaped abrader fragment. Ground on both surfaces and side. Kimta Road dumped material. (5.2)x(4.3)x1.6)cm.

DcRu-116:25. Ground portion of beach pebble. This was originally a naturally flattened and round edged cobble that was fractured into a few pieces. It may have been a larger complete ground cobble artifact that was broken. However, wear patterns extend over the two fractured edges showing that the stone was used after the original stone was fractured into portions. There is heavy grinding, mostly on one larger surface, of the portion of the original cobble that remains. The long side and to a lesser extent, the shorter end have been ground. There are numerous very fine scratches in all directions on the two smoothed and polished surfaces of this cobble. Its function is unknown, but it could be a rubbing stone for rubbing substances into and compressing wood, such as various practices in treating canoes. Provenience: N9.08 E.18.40. DBD79cm. (6.8)x(4.6)x(2.3).

Sub-class: Fabrication Tools. Hammerstone.

DcRu-116:23. Hammer stone. Elongate coarse sandstone cobble, pecking on one end. Provenience: N8-9.0 E18-20m. DBD 65-70cm. In ash, crushed shell and dark brown soil. 9.4×5.1×3.8cm.

Figure 17. DcRu-116:23. Sandstone Hammer.

Sub-class: Fabrication Tools. Worked stone flakes.

DcRu-116:20. Retouched stone Flake. One long side and the distal end of this flake are intentionally retouched to create a special use edge. This could have been used for shaving hard wood. N9-9.8 E19-20. DBD 60-68cm. 3.8×2.15×0.65cm.

DcRu-116:16. Use retouched flake. Fine grained grey chert. Tiny flaking on two edges suggest this may have been used as a scrapping tool. Given that it was found on the surface the damage on the fine edges could be a result of recent crushing. Provenience: Surface at the Capital Iron site. 3.9×2.8×1.15cm.

DcRu-116:41. Use retouched flake. A few areas of tiny flaking suggest this fine dacite flake may have been used as a scrapping tool. Provenience: Kimta Road midden.4.2×3.4×1.1cm.

DcRu-116:5. Flake with bifacial flaking on one side. Basalt. This is likely a flake fractured off a larger piece in an attempt to make a projectile point. N10.23 E19.20. DBD 38cm. 3.5×2.5×1.1cm.

Figure 18. Worked Stone flakes. DcRu-116:20;41;16;5

TEST

Sub-class: Debitage. Antler.

Figure 19. Worked elk antler debitage. DcRu-116:32.

DcRu-116:32. Antler. The base portion of an elk antler that has been chopped off and subsequently chewed by rodents. Disturbed surface deposits at Capital Iron. 10.4×7.7×4.1cm.

Sub-class: Debitage. Flaked Stone.

In urban areas, fine grained rocks crushed by machinery can be found scattered about, especially when used on pathways and fill around houses and in cement structures. It is not uncommon in this environment to find what falsely appear to be ancient flakes or cores discarded in tool manufacture. Since many of the items described here are from disturbed deposits – that is midden mixed with other material of unknown origin – we need to be cautious that some may be of more recent non-First Nations activity. Many of the flakes do have an old surface patina demonstrating that they are ancient. I have included two that I have determined are of a recent nature – numbers 11 and 30. Artifact no. 11 was found in the 0-30cm level of unit 2 – indicating some historic disturbance in this upper level.

From my own experience of collecting and flaking many thousands of stones from many sources in the greater Victoria Region, I am able to observe there are what I would call field cobbles and beach cobbles. Where the original outside cortex of the flaked basalt is present, field cobbles have a duller and mottled heavy patina on the outer surface as opposed to beach or stream cobbles which have smoothed surfaces and less evident outside patina. DcRu-16:49 and DcRu-116:46 are examples of the latter types. X-ray analysis is needed to see if these types have any compositional differences. One item, DcRu-116:128, is not flaked, but is a fire-exploded cubicle piece of fine basalt or dacite that may have been intentionally heat treated and intended as a core of raw material.

DcRu-116:46. Basalt Core segment. Original cortex on two sides. Field basalt based on surface texture. Kimta road dumped midden. 5.66×4.40×3.6cm.

Figure 20. Two types of surface texture. Mottled surface of field cobble (DcRu-116:46) on left and smoother surface beach cobble (DcRu-116:49.

Figure 21. Flakes with original cortex surface. DcRu-116:54:47:45:43:50:55.

DcRu-116:49. Basalt Flake with cortex on one side. Beach cobble based on surface texture. Kimta road dumped midden. 7.6×3.8×1.9cm.

DcRu-116:54. Flake with original cortical surface on one edge. Kimta Road midden. 3.4×2.7×1.3.

DcRu-116:45. This is a section of a cobble that has been formed by bi-polar percussion – that is, smashing one end of the cobble while the other end rests on a stone anvil. It is a very hard chert-like material. Kimta Road midden.

DcRu-116:47. Flake with most of the original cortical surface on one side. 5.16×3.36×1.35cm. Kimta Road midden.

DcRu-116:43. Large flake of basalt. Some original cortical surface. 7.4×4.1×1.1cm. 6.11×4.00×1.61. Kimta Road midden.

DcRu-116:50. Core segment with remnants of the original cortical surface remaining on one end. Provenience: Kimta Road midden.

DcRu-116:55. Large flake of basalt. Some original cortical surface remaining on one end and in small amounts of two thin edges. 4.6×4.1×1.8. Kimta Road midden.

DcRu-116:2. Basalt core segment. N 8.52m E18.19m. Upper level. 4.85×4.0x1.5cm.

DcRu-116:42. Basalt flake. Some recent edge crushing. 3.9cmx2.8cmx0.5cm.

DcRu-116:48. Basalt flake. Some recent edge crushing.

DcRu-116:53. Basalt flake. Some recent edge crushing.

Figure 22. Stone detritus from Tool making. DcRu-116:42;48;53;2

DcRu-116:4. Small percussion flake that likely came off a core with the removal of larger flakes. Although it has a similar size as some micro-blades, it is not a pressure flaked micro-blade. Surface at Capital Iron site. 1.25×0.8×0.25cm.

List of Debitage within the DcRu-116:59-133 range.

In 1992, I extracted the following artifacts from the 1976 excavation level bags that were labelled as to provenience in the excavation units. Exceptions are numbers 129-132 from the Kimta Road midden that were originally lumped together as #49.

Measurements are not given, as anyone undertaking lithic analysis would want to measure the artifacts in a prescribed way and develop more specific descriptions of flake morphology. The majority of these are basalt, andesite and other volcanic rocks.

DcRu-116:64-65(Pit 1,Level 1, 10-20cm); DcRu-116:60(Pit 1, Lev. 3, 30-40cm); DcRu-116:66-67 (Pit 1, Lev. 4, 40-50cm); DcRu-116:101-107 (Pit 1, Lev. 5, 50-60cm); DcRu-116:59&76-88 (Pit 1, Lev. 6, 60-70cm); DcRu-116:121-127 (Pit 1, Lev. 7, 70-80cm); DcRu-116:117-120 (Pit 1, Lev. 8, 80-90cm); DcRu-116:89-90 (Pit 1, Lev. 10, 100-110cm). DcRu-116:100&128 (Pit 2, Lev. 2, 20-30cm); DcRu-116:61-63 (Pit 2, Lev. 3, 30-40cm); DcRu-116:68-75&133 (Pit 2, Lev. 4, 40-50cm); DcRu-116:91-99 (Pit 2, Lev. 6, 60-70cm); DcRu-116:108-116 (Pit 2, Lev. 7, 70-80cm).

Figure 27. Basalt core or raw material. DcRu-116:38.

DcRu-116:38. Basalt core or raw material. Large five sided core of coarse grained basalt. Flakes are fractured from two faces resulting from single impact point on the corner of one side. This could be a raw material sample that was tested by removing a flake or a piece of unworked raw material brought to the site in ancient times and subsequently struck once by modern machinery while being dug up. Kimta road dumped midden. 9.3×9.2×6.8cm.

Modern stone artifacts

Two stone artifacts are of a recent nature. DcRu-116:11 is a section of a quartzite cobble that has been formed by heavy bi-polar percussion. It was found in a disturbed level with historic materials. Modern commercial cement is still adhering to the rock. This appears to be a mechanically crushed rock that was inside a cement structure. N10-12 E18-20.DBD 0-30cm. 5.9×4.5×1.8cm. DcRu-116:30 is a small spall off of a large cobble that was removed with enormous force. Although spall tool artifacts are occasionally found in ancient sites, this one exhibits a large secondary outside spall and a crushed point of impact which is typical of recent machine crushed rock.

Figure 28. DcRu-116:11 & 30. Modern machine crushed pebbles.

Provenience: Kimta Road midden. 5.6×4.75×1.5cm.

Private Collection Artifact

In March of 1991, I observed shell midden at the west end of the parking lot located at the S.W. corner of Store and Chatham Streets. It had been exposed by large truck ruts. I observed a nephrite adze blade found by a private citizen at this location. The 9.5cm long adze blade had a cutting edge that was beveled mostly on one side with a slight bevel on the other. It measured 6cm across the cutting end and 3.4cm across the poll end. It was thickest, 1.4cm, near the cutting end and 1.2cm thick at the poll end.

Observations of DcRu-116 in 2014.

Midden deposits were found underneath a small building on Store Street when it was being torn down in 2014. This location was to the north of the 1976 excavation area. On November 20, 2014 I visited the site to examine and photograph the exposed shell midden. The upper portions of the midden were disturbed by historic non-First Nations activity, but the southern lower portions were intact.

Midden Content Observations

Figure 32, shows a close-up of the shell midden which is composed mostly of native oyster shell. In a close examination of the exposed midden, I observed many small weathered beach pebbles (1-3cm) mixed in with the shell fish remains. There are no local inner harbour beaches that could be the source of these small pebbles. They are similar to the small pebbles that one often observes entangled in the roots of the Bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana), that has been pulled up either by storms or by people. I would suggest that these pebbles came to this site when First Nations brought large canoe loads of kelp that they processed on the site for making a variety of items. The long stalks of Bull kelp were dried and cured, and spliced or plaited together to make ropes, nets, and fishing, harpoon and anchor lines. Kelp bulbs were also used for liquid storage and for steam bending wooden fish hooks.

In 2014, Stantec undertook archaeological work on the site under alteration Permit 2014-0300. This work resulted in the removal of the last of the shell midden from the west side of Store Street.

Figure 33. Stantec monitoring removal of Midden. Tom Bown photograph October 31, 2014.

Figure 34. Site location after archaeological monitoring and removal of cultural material. Grant Keddie photograph December 3, 2014.

Summary

The Capital Iron site, DcRu-116, is one of only three pre-contact archaeological sites in Victoria’s Inner Harbour. The other two are located on rocky bluff peninsulas at Raymur Point and Lime Point across from each other near the entrance to the inner harbour. The Lime Point site dating between 600 and 1200 years old is a known defensive site – having once had a trench embankment dug around the back end of the peninsula. The Capital Iron site was first occupied earlier around 260A.D. to 424 A.D. It is likely that the location of the Capital Iron site was chosen for both economic reasons and its defensive features – being high above the beach with a good view of the harbour. Modern development has now destroyed all of the Lime Point site and most of the Raymur Point site.

DcRu-116 has been heavily impacted by historic activities. The recovery of information has been piecemeal but has begun to build a story of the human activities that occurred here in the past. The recovery of more information from any intact midden will help to build a more complete picture.

Future archaeological work at DcRu-116.

The shell midden is now mostly or all gone from the west side of Store Street on the property around the Capital Iron Buildings. The low areas near the water are landfill on a previous embayment that will not contain any intact midden.

Portions of site DcRu-116 are known to exist under Store Street east of the Capital Iron buildings and extending, at least, onto the parking lot at the S.E. corner of Chatham and Store Streets. If some of this midden is still in-tact, it will be important to recover an adequate faunal sample that was not recovered in the 1976 excavations due to the rushed emergency nature of that project and also to get more radio carbon dates to provide a better time frame as to when the site was occupied. This site has the potential to be a valuable source of information on the history of Lekwungen peoples and their use of Victoria Harbour.

Appendix 1

Historic Disturbance of the Archaeological Site Location

Lot 114 adjacent to the south of the excavation area was owned by a J. Crow in 1861 (Victoria Archive tax assessment records). Extensive activities, modifying the landscape began in this area with the building of the two story stone warehouse of Dickson and Campbell & Co. on lot 114, with a wharf and other buildings adjacent (they later bought lot 113). The three foot thick walls were “built of granite, blasted from the adjoining primeval rock” (Colonist October 31, 1862 & September 8, 1863).

Figure 35. The Dickson and Campbell & Co building (later the Capital Iron building) on the far right in 1863.

In 1885, the location had become the Mount Royal Milling and Manufacturing Co. on lot 113 (two floors added) and Joseph D. Pemberton’s Royal Milling and Manufacturing Co. on lot 114. These properties later became part of the Capital Iron and Metal Company property at 1900 Store Street (an earlier address was 1832 Store Street).

It is likely that some intact midden still exists beneath Store Street and extending onto the properties east of Store Street on both sides of Chatham Street. Less disturbance of the landscape has occurred in the past on the south side of Chatham. I observed shell midden at this parking lot location in the 1970s when some shallow bulldozing activity was undertaken. A private citizen found a stone nephrite adze blade for a work working tool in exposed shell midden at this location.

On the north side of Chatham Street extensive disturbance occurred beginning in 1862, with development of the Albion Iron Works facilities. This included Foundry buildings, machine shops and a sequence of other buildings (see 1885 Fire Map for later changes).

Figure 36. 1885 Fire Map.

After the Iron works closed the railway was extended into this area (see 1957 Fire Map). Large amounts of land fill were dumped in the area, especially toward Government Street where bottle diggers, during the 1960’s and early 1970s, uncovered large amounts of refuge that came from the Brewery site on the other side of Government Street.

Figure 37. 1957 Fire Map.

In the 1970s, I was aware of an old lantern slide in the Royal BC Museum ethnology collection that I later identified as a Songhees First Nation. I based my information on the original field portrait catalogue of Paul Kane – created when he was at Fort Victoria in 1847 (Harper 1971:315-317). I did not know at the time the original sketch was missing, and this seemed to be the only image of it.

Figure 1. Photograph of a missing sketch by Paul Kane, 1906. Charles Newcombe. PN17161.

Figure 1, is No. 46 in Paul Kane’s portrait log: “Ska-tel-san – a Samas Tillicum with a (grass) hat that is much worn here south of de Fuca”, and in his Exhibition of 1848 he is listed as: “124 Sca-tel-son – a Songhes Indian, Vancouver’s Island” (Harper 1971:316 & 319).

A painting in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM912.1.870) was made from this original sketch. Harper was led into miss-labelling the latter as “A Babine chief” (1971:265). There was a mix-up of information during exhibits of Kane’s work, where various writings and collection lists, rather than his original accurate field logs, were used as source information. Incorrect identifications in publications of Kane’s friend Daniel Wilson also contributed to the confusion in names.

Figure 2. Lithograph of painting of Sir Daniel Wilson, Published in 1862.

Lister in his Paul Kane/the Artist/: Wilderness to Studio (fig.58; 2010:301) and again in his editing of Wonderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America (Plate 60; 2017: 242-243) labels this later painting (ROM912.1.87) as “A Babbine Chief. Tsimshian. Skeena River region, northwest British Columbia.” He records that the description is based on “A list of Pictures sent to Mr. G.W. Allan, March 6, 1856”. Harper’s speculation on this painting in his Catalogue Raisonne IV-587, is correct: “This canvas is probably based on an unlocated sketch. When lithographed for the frontispiece in the Wilson book, Prehistoric Man, the title was changed to “Chimseyan Chief” (Harper 1971:308).

Figure 2, shows a lithograph of a painting by historian and artist Sir Daniel Wilson copied from the missing Paul Kane original. This did appear in volume I of Wilson’s 1862 publication.

In the third edition (1876) of Volume 1, of Wilson’s Prehistoric Man, this person is noted as “Kaskatachyuh, a Chimpseyan” Chief”, where it is noted that Wilson drew it “from sketches by Paul Kane”. Wilson, in discussions about what are obviously Haida argillite pipes, refers to them as those of the “Babeen Indians”, and mentions, mistakenly (in the second part), that they are: “from a drawing made by Mr. Kane, during his residence among the Babeen Indians” (Wilson 1857:42). Paul Kane never went to the northern coast of British Columbia, and First Nation visitors from that region did not come to the Victoria area until after Paul Kane’s visit. A few First Nations from the central and northern coast of British Columbia did work at the Hudson’s Bay posts, but there is no indication that these were the source of Kane’s sketches.

In the mid-19th century, accurate writing about the First Nations of British Columbia was lacking. Kane’s historian friend, Daniel Wilson, kept current with the ethnographic literature of the times, such as the writings of geographer and ethnologist Henry Schoolcraft, but often lumped unrelated groups together or got their geographic locations wrong. Wilson was likely a strong influence on the use of First Nation names in the Paul Kane writings and exhibits.

This Songhees person in Wilson’s (1862, Vol. 1) frontispiece, is also the same person, but from the original Kane sketch in reverse image in my book (Keddie 2003:3). I have since realized that lantern slide RBCM PNH104 was mistakenly photographed in reverse. I have identified the person as Sketlesun, a Songhees from the old Cadboro Bay village. He is the 6th person on the Che-ko-nein treaty list of 1850. Because Sketlesun is wearing a Chilkat blanket and northern style hat, this image has been mistakenly labelled as a “Tsimshian chief” (Keddie, 2003:30). This style of Chilkat blanket was a valuable and high status trade item in the mid-19th century. Kane had purchased his own Chilkat blankets (see Lister 2010), but used designs from at least two different ones in his portraits.

In 1906, Charles Newcombe took, at least twelve, photographs of Kane paintings. In regard to three of these (not figure 1) that he published, he notes they are: “reproduced by kind permission of E.B. Osler, Esq, M.P., of Toronto, who owns the originals” (Newcombe, 1909:53). He also acquired copies of paintings that were used in Daniel Wilson’s, two volumes – Prehistoric Man: Researches into the Origin of Civilisation in the Old and the New World (Wilson 1862). Wilson made copies of several of Kane’s sketches for use in these and other publications.

I have now found the original negative from which Newcombe’s lantern slide was made (RBCM PN17161). Newcombe seemed to accept the naming of this image as Tsimshian because of the cape – not having access to Kane’s field catalogues at this time. It is clear that the photograph taken by Newcombe of Kane’s No. 46 portrait is a photograph of what Harper referred to as Kane’s “unlocated sketch”. I do not know where the original is, but this photograph might lead to its re-discovery.

Edmund Osler had much of his collection on loan to the University of Toronto from 1904, until it became part of the Royal Ontario Museum collection in 1912 (Harper 1971:35). We know that in 1906 Charles Newcombe was in Montreal visiting “Dr. Lowe” to see his collection on June 2, and the next day visited the Red Path Museum. On June 10, he was in New York and around that time visited the Field Museum of Chicago. Somewhere after Newcombe took photographs of the collection(s), the sketch of the Songhees man named Sketlesun, referred to in Kane’s portrait log, disappeared or lies unidentified in some collection.

References

Harper, Russell J. 1971. Paul Kane’s Frontier. Including Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America by Paul Kane. Edited with a Biographical Introduction and a Catalogue Raisonne by J. Russel Harper. The Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Keddie, Grant. 2003. Songhees Pictorial. A History of the Songhees People as seen by Outsiders, 1790-1912. Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria.

Lister, Kenneth R. 2016. (Editor) Wonderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America by Paul Kane. Royal Ontario Museum.

Lister, Kenneth R. 2010. Paul Kane/the Artist/: Wilderness to Studio. Royal Ontario Museum Press, Toronto.

Newcombe, Charles. 1909. Guide to Anthropological Collection in the Provincial Museum, King’s Printer, Victoria, B.C.

Wilson, Daniel. 1857. Pipes and Tobacco: An Ethnographic Sketch. Lovell and Gibson, Toronto.

Wilson, Daniel. 1862. Prehistoric Man: Researches into the Origin of Civilisation in the Old and the New World, McMillan, Cambridge.

There is an ancient archaeological shell midden – the refuse from what was once, at least, a seasonal camp on Raymur Point at the intersection of St. Laurence Street and Kingston Avenue. Raymur Point is a raised bedrock peninsula on the south side of Victoria’s inner harbour located to the west of Laurel Point and at the east end of Fisherman’s Wharf. The site was not occupied by First Nations in historic times and appears to have had a limited occupation in the distant past.

Figure 1. Western portion of Victoria’s Inner Harbour in 1878. Shoal Point in the foreground is the start of the inner harbour. Raymur Point can be seen as a small peninsula with a house on it at the centre of the right side of this lithograph. Close up of Bird’s Eye View of Victoria, 1878. RBCM PDP-02625 .

The midden location, known as Archaeological site DcRu-33, includes the extreme northern extension of the point and the shoreline along the wider section of the point extending along the west shore to the area around lots 1291 and 1292 on the west side of St. Lawrence Street.

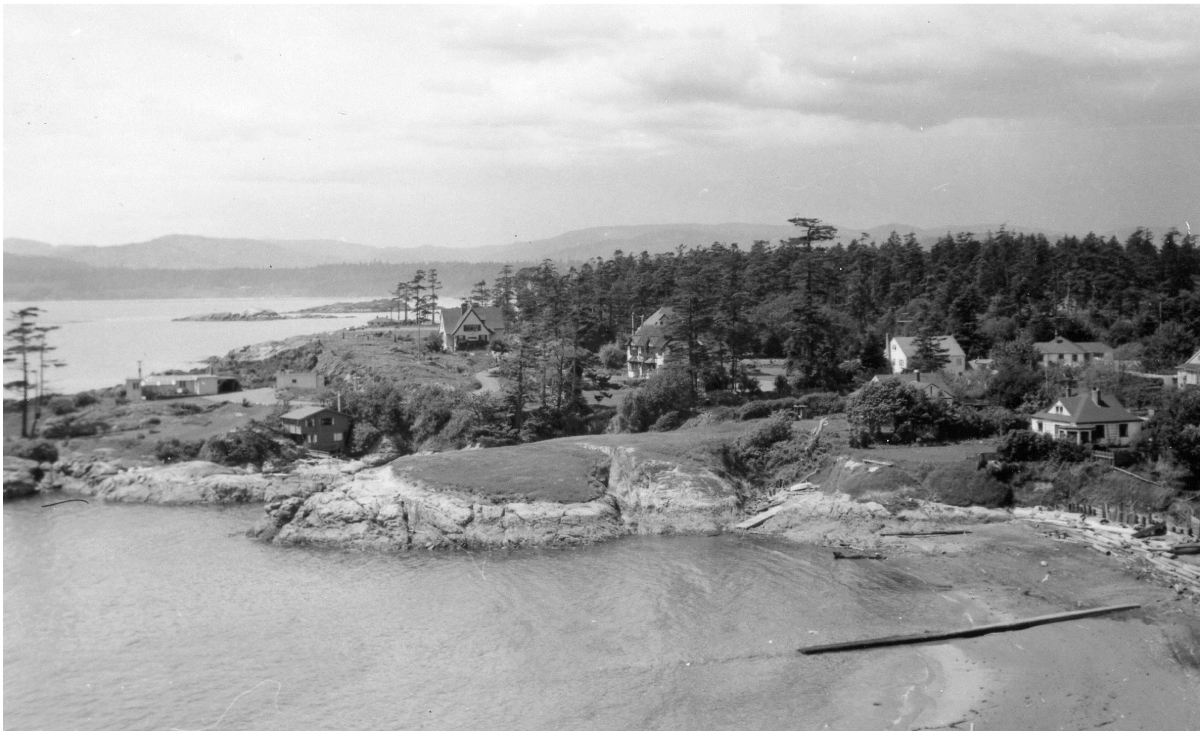

The site is now mostly destroyed by the building and clearance of the large Texaco Oil storage tanks that were here until the 1980s (see figure 10), and the more recent building of apartment units. Midden may still be intact on some parts of the adjoining lots 1291 and 1292. The latter locations were not included in the last Archaeological work undertaken on the site in 1998 (Hewer 1998).

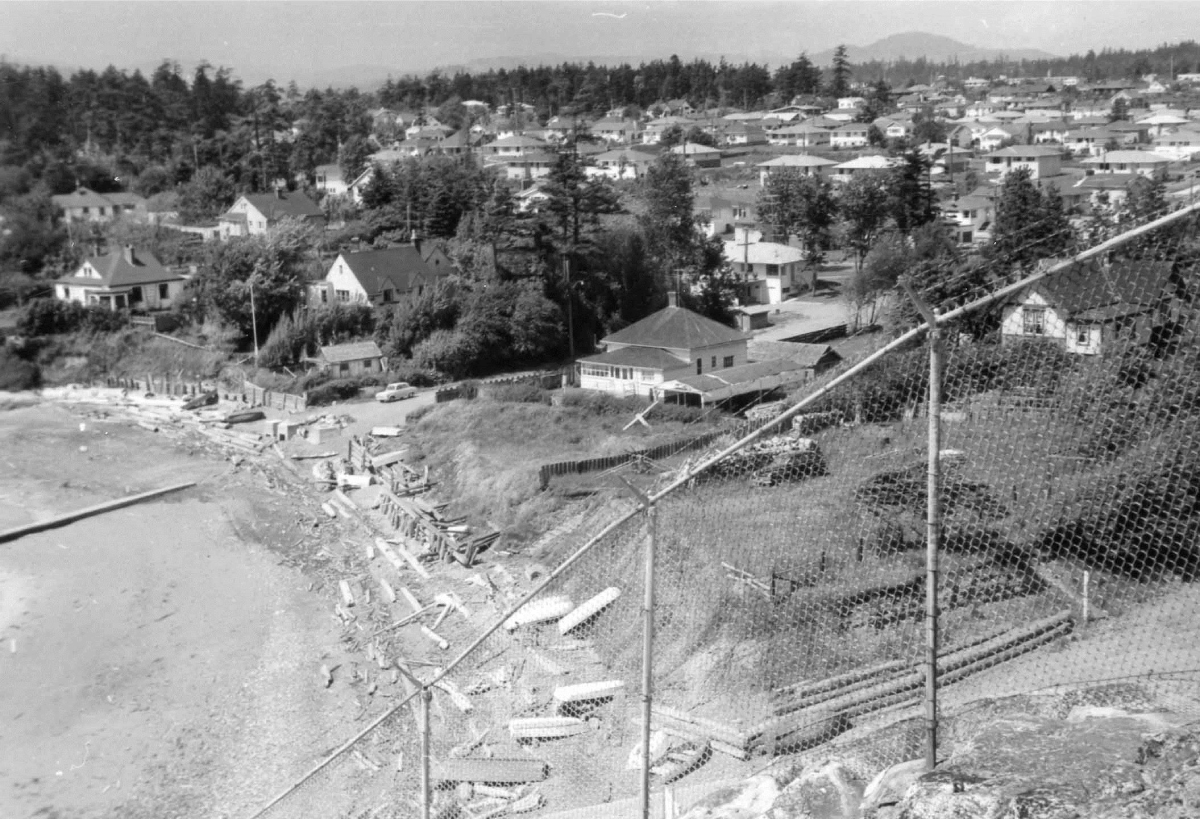

The original configuration of the peninsula can be seen in Figure 2. The large home just to the right of the centre of this photograph is still on lot 1291 near the corner of St. Lawrence and Kingston Street’s.

Figure 2. Raymur Point in the late 1890s. Richard Maynard Photograph. BCA A-3457.

An 1890s, close up of the northern tip of the Point can be seen in Figure 3. This shows the area of the (then) probably undisturbed midden. The midden eroding over the bank can be seen in Figure 4. I took photographs in March 1990, during the digging out of the foundations left over from the removed of oil tanks.

Figure 3. North end of Raymur Point at centre. The house on the right is located beyond the next small bay and not on Raymur Point. Close-up of RBCM F-9653.

Figure 4. Midden eroding out of a crevice.

The house on lot 1291 can be seen in figure 5. This photograph shows the west side of the site where only disturbed midden and extensive rock fill existed in the foreground in 1990. Figure 6, shows the north end of the site where midden can be seen slumping down the bank into a tiny embayment in the bed rock. It is below this area where I collected some of the artifacts.

Figure 5. The west side of the site in 1990, showing disturbed shell midden. Grant Keddie photograph.

The east side of the site is seen in Figure 7. This area was previously destroyed and now being dug up again. The northern tip of Raymur Point is on the other side of the bulldozer in the photo. The now destroyed Lime Bay First Nations defensive site, DcRu-123, can be seen across the harbour in the form of the knoll just to the right of the backhoe.

Figure 6. The north end of Raymur Point in 1990, before the condominium development. Midden can be seen eroding down the face of the bedrock. Grant Keddie photograph.

Figure 7. Looking North on East side of Raymur Point.

Figure 8. Looking east at the black midden on the outside of the cement wall.

Figure 9. The same bedrock area seen in Figure 6, after 25 years of erosion. Grant Keddie photograph, 2015.

Figure 10. Raymur Point covered with oil storage tanks. Keddie photograph 1986.

Figure 11. Raymur Point on right with dock on north end. Keddie photograph July 29, 1993.

Figure 12. Raymur Point as it looked on March 29, 2012. Looking east from the Fisherman’s Wharf Area.

The Midden Contents

On May 8, 1986, I observed that the shell midden was composed of mostly native little neck and butter clams, and some cockle clams and barnacles. This is not the unusual kind of mollusks found in other ancient sites in Victoria’s inner harbour and those further up the Gorge Waterway. The latter contain mostly native oyster shells.

The site contained many fire-altered rocks, scattered throughout the midden. These were traditionally used for steaming or boiling food. Most artifacts found in the site were stone waste materials, such as cores and flakes, resulting from the making of stone tools. These, the other limited artifact contents of the site, and the shallowness of the cultural deposits indicate that the location was occupied for a limited time, at least on a seasonal basis, around 2000 years ago.

A single human burial was recovered from the site in 1956, when constructing a cement wall. These remains were subsequently re-buried in the cemetery on the Songhees reserve. I located and talked to the bulldozer operator who worked on the site in 1956. He told me that the burial was in a flexed or fetal position. He observed that most of the midden was concentrated toward the east of Raymurs Point, where midden can still be seen eroding down the bank today.

On May 7, 1991, I examined the excavation trench for a waterline installation around the north side of the centre line on Kingston and St. Lawrence. There was no midden under St. Lawrence Street in front of 1293, 1292 and 1291 lots or under the Kingston Street and St. Lawrence intersection.

The Artifacts